For a presidential candidate one of the best ways to communicate directly with the electorates is to have effective campaign posters. There is no doubt that people respond to posters. A good poster, like Bill Clinton's of 1996, creates a positive impact and a bad poster, like those of George H. W. Bush and his rival Michael Dukakis of 1988, does the opposite. A good poster should create an iconic image, that as Robert Hariman and John Lucaites, in their study of iconic photographs, state can be:

"widely recognized and remembered, are understood to be representations of historically significant events, activate strong emotional identification or response, and are reproduced across a range of media, genres, or topics.”

According to semiotician Roland Barthes the electoral photograph functions like a mirror to the viewer and “offers to the voter his own likeness, but clarified, exalted, superbly elevated into a type” through which the viewer is “invited to elect himself.” Traditionally an idealized portrait follows a grammar which typically is structured around three-quarters poses, conveying a certain aura of leadership quality to the person being depicted. In this grammar, the subjects look away from the viewer with a gaze that does not acknowledge their presence, suggesting authority, accomplishment, and imagination — someone who is leading toward prosperity and prgress.

A good poster like that of Andrew Jackson's poster of 1828, Zacharias Taylor of 1848, Ulysses Grant of 1868, William Jennings Bryan of 1896, and the best of them all; that of Theodore Roosevelt of 1901, should be easy to read, well balanced and aesthetically pleasing. A positive and powerful typography in a poster that prominently features the candidate's portrait and distinctly state the candidate's name and the main message of the campaign for what the candidate hopes to accomplish during his mandate is a definitive must.

An accurate and honest slogan like;

The Union Must be Preserved, of Jackson's poster of 1828,

I Want You FDR, Stay and Finish the Job! of FDR's of 1944, or

Leadership for the 60s of JFK's 1960, which would speak to people's anxieties and wishes and would capture the essence of the campaign is crutially important. Such slogans help people to easily remember why they are voting.

US Presidential Campaigns

|

According to W. Ralph Eubanks, publishing director at the Library of Congress 1828 was the beginning of modern presidential campaigns, since it was the first election in which the electorates didn't have to own property to vote,

The race for the White House in 1828 pitted incumbent John Quincy Adams against Andrew Jackson, hero of the Battle of New Orleans. The beginning of the 1828 campaign revealed little difference between the two candidates on the major political issues of the day - maintaining protective tariffs and encouraging national improvement.

Jackson was America's first "Frontier President" – the first president who did not come from the nation’s east-coast elite. It became obvious that the race would be a personality contest and that Jackson had the clear lead. His victory was seen as a triumph for the common man and for democracy. |

|

Martin Van Buren built astrong friendship and political

alliance with President Jackson and so in

1836 when he ran to succeed him, Jackson and key members of the Democratic Party rallied behind him. Van Buren's running mate was Congressman Richard Johnson of Kentucky.

The severe recession that wracked the American economy during the late 1830s was caused by English banks, that faced with financial troubles at home—stopped pumping money into the American economy, and U.S. banks, which did the same because they had overextended credit to their clients. These, together with President Andrew Jackson's tight monetary policies, that exacerbated the credit crunch, mired down the Van Buren presidency.

In late 1837, a small Canadian separatist movement sought to gain independence from Britain and a number of American citizens began selling guns and supplies to them. In response, the British ordered loyalist Canadian forces to attack the supply ship. The loyalist Canadians boarded the Caroline, set it ablaze, and pushed it over Niagara Falls, killing one American. Considerable sentiment arose within the United States to declare war on England, and a British ship was burned in revenge. But Van Buren's patient diplomacy, defused tensions between the the two countries and kept America out of war. |

|

| Henry Clay, the Whigs most prominent congressional leader, was nominated along with Theodore Frelinghuysen as his running mate in the 1844 election. They were defeated by Democratic party's nominee James K. Polk, who ran on a platform embracing American territorial expansionism, an idea soon to be referred to as Manifest Destiny. |

. |

| At their convention of 1844, the Democrats called for the annexation of Texas and asserted that the United States had a “clear and unquestionable” claim to “the whole” of Oregon. By informally tying the Oregon boundary dispute to the more controversial Texas debate, the Democrats appealed to both Northern expansionists (who were more adamant about the Oregon boundary) and Southern expansionists (who were more focused on annexing Texas as a slave state). Polk went on to win a narrow victory over Whig candidate Henry Clay, in part because Clay had taken a stand against expansion, although economic issues were also of great importance. |

|

| Lewis Cass was the nominee of the Democratic Party for President of the United States in 1848. |

|

| In 1848, Lewis Cass resigned from the Senate to run for President. William Orlando Butler

was his running mate. Cass was a leading supporter of the Doctrine of Popular Sovereignty, which held that the people who lived in a territory should decide whether or not to permit slavery there. His nomination caused a split in the Democratic party, leading many antislavery Democrats to join the Free Soil Party. He also supported the annexation of Texas. After losing the election to Zachary Taylor, he returned to the Senate |

|

Zacharias Taylor Campaign Poster (1848)

Taylor's victories wars in Texas and Mexico as an army general set off his presidential boom, especially when it became clear that he was a Whig. In 1848 he received the Whig nomination and won the presidency. At the time he became President, Zachary Taylor was the most popular

man in America, a hero of the Mexican-American War.

Taylor was a wealthy slave owner who held properties in the plantation states of Louisiana, Kentucky, and Mississippi. During his

brief time in office—he died only sixteen months after his election—his presidency foundered over the question of whether the national government should permit the spread of slavery to the present-day states of California, New Mexico, and Utah, then newly won from Mexico. His sudden death put Vice President Millard Fillmore into the White House.

|

|

|

| Presidential Campaign. Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore |

|

| In 1848, the Whigs nominated Fillmore as vice president, and he was elected with Zachary Taylor. He became president on Taylor's death in 1850. Though he abhorred slavery, he supported the Compromise of 1850 and insisted on federal enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act. His stand, which alienated the North, led to his defeat by Winfield Scott at the Whigs' nominating convention in 1852. |

|

The 1856 presidential election was focused on the singular issue of states' rights and the resultant policy allowing slavery in the United States. The infant Republican Party, still mostly a party of the northern and western states, decided to nominate famous explorer and California governor John C. Fremont as its standard bearer. Former president Millard Fillmore was nominated the candidate of the Know Nothing Party, a largely northern party that was anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic. Fillmore's campaign consisted largely of criticizing Fremont and the Republican's reckless attempt at ending slavery.

Buchanan, of Democratic Party, felt strongly that states should determine the future of slavery, while Fremont considered the economic aspects of slavery as the main factor in the federal government's stake in ending slavery. In the end, Fremont's rampant abolitionist tendencies led to his removal from Southern ballots and the threat by Southern governors to secede from the Union should Fremont become president. As well, the Know Nothings spent time attacking Fremont and were successful in taking away votes from the Republicans in rural areas where anti-immigrant tendencies existed. As a result of the split vote James Buchanan would win the election. |

|

In January 1852 the legislature of New Hampshire proposed Franklin Pierce as a candidate for the presidency, and when the Democratic national convention met at Baltimore in the following June he became the Democratic candidate. Although both parties had declared the Compromise of 1850 a finality, the Democrats alone were thoroughly united in support of this declaration, and therefore seemed to offer the greater prospect of peace. Pierce swept the country at the November election. and the Democrats carried every state except Massachusetts, Vermont, Kentucky and Tennessee.

When the Democratic national convention met at Cincinnati in June 1856, Pierce was an avowed candidate for renomination, but as his attitude on the slavery question, and especially his appeasement of the South by supporting the pro-slavery party in the Territory of Kansas, had lost him the support of the Northern wing of his party, the nomination went to James Buchanan.

|

|

In 1856 Buchanan won his party's nomination and faced Republican John

Fremont and Know-Nothing Millard Fillmore in a campaign that revolved around the expansion of slavery and the escalating tensions in Kansas. As Kansas degenerated into violence, Buchanan managed to win the south and four northern states, giving him a comfortable victory over Fremont.

As president, Buchanan proved unable to stem the violence in Kansas or to produce any sort of workable regional compromise. After Republican Abraham Lincoln won the presidential election of 1860, southern states began to secede. Other than refusing to give up Fort Sumter in South Carolina, Buchanan did little to hinder the breakup of the nation. When he handed over the presidency to Lincoln on March 4, 1861, there was little doubt that war was at hand. |

|

|

|

As the most activist President in history, Lincoln transformed the President's role as commander in chief and as chief executive into a powerful new position, making the President supreme over both Congress and the courts. His activism began almost immediately with Fort Sumter when he called out state militias, expanded the army and navy, spent $2 million without congressional appropriation, blockaded southern ports, closed post offices to treasonable correspondences, suspended the writ of habeas corpus in several locations, ordered the arrest and military detention of suspected traitors, and issued the Emancipation Proclamation on New Year's Day 1863.

To do all of these things, Lincoln broke an assortment of laws and ignored one constitutional provision after another. He made war without a declaration of war, and indeed even before summoning Congress into special session. He countered Supreme Court opposition by affirming his own version of judicial review that placed the President as the final interpreter of the Constitution. For Lincoln, it made no sense "to lose the nation and yet preserve the Constitution." Following a strategy of "unilateral action," Lincoln justified his powers as an emergency authority granted to him by the people. He had been elected, he told his critics, to decide when an emergency existed and to take all measures required to deal with it. In doing so, Lincoln maintained that the President was one of three "coordinate" departments of government, not in any way subordinate to Congress or the courts. Moreover, he demonstrated that the President had a special duty that went beyond the duty of Congress and the courts, a duty that required constant executive action in times of crisis. While the other branches of government are required to support the Constitution, Lincoln's actions pointed to the notion that the President alone is sworn to preserve, protect, and defend it. In times of war, this power makes the President literally responsible for the well-being and survival of the nation

|

|

| The Presidential Election of 1868 saw Grant and Colfax successfully run against New York Democratic Governor, Horatio Seymour and his running mate Francis Blair, Jr. As a result of the election, Ulysses S. Grant became the 18th President of the United States, and became the first President elected since the abolishment of slavery. |

|

Creditors, and orthodox financial circles, demanded the redemption of greenbacks with gold and silver after the Civil War. The Public Credit Act of 1869 pledged the federal government to such a policy. It would cause deflation, which raised interest rates and made the money that creditors owned more valuable. Naturally, they wrapped their self-interest in a blanket of moralistic slogans. Honest money, they claimed, was necessary to convince capitalists of the long-term stability of the dollar. Otherwise, investors would be timid and stunt the nation's growth. Debtors, especially in the cash‑poor South and West, complained that deflation would force them to sell more products to make the same dollar they had borrowed, in addition to paying higher interest rates because money was scarce.

The proto-Populist Greenback and Union Labor parties of the 1870s and 1880s made monetary policy one of their premier issues. Supporters considered labor to be the only legitimate source of value. Thus, money was simply a means of keeping count of one's labor. It needed only government fiat, not intrinsic value. Greenbackers argued that the federal government should maintain stable values by adjusting the money supply to match changes in population and production. During the deflationary Gilded Age this would mean expanding the money supply. The federal government could easily do this with greenbacks. But, the supply of gold and silver could not be controlled. Commitment to intrinsic money caused deflation which automatically increased the purchasing power of the wealthy. Greenbackers considered this illegitimate because it allowed the rich to amass wealth without labor.

In November, 1874, Indiana Independents founded the National Independent, or Greenback, Party. Greenbackers nominated Peter Cooper of New York for president in 1876. Their platform called for repeal of the Resumption Act of 1875 and the issuance of legal tender notes. Drawing voters away from the mainstream parties, however, proved difficult in this era of highly partisan politics. For many, political affiliation was almost akin to church membership. Thus, Cooper polled a minuscule vote, mostly from the Midwest, in 1876.

|

|

Campaign poster for presidential candidate James A. Garfield (1831-81) and running mate, Chester A. Arthur (1829-86) 1880.

In an era when it was still considered unseemly for a candidate to court voters actively, Garfield conducted the first “front-porch” campaign, from his home in Mentor, Ohio, where reporters and voters went to hear him speak.Because President Rutherford B. Hayes had pledged to serve only one term, the run-up to the 1880 election saw both major parties to designate a new candidate. Though his presidency had been marred by scandal, the conservative faction of the Republican Party favoured former president Ulysses S. Grant. While he did not actively seek the nomination, it was understood that he would accept it if offered. At the nominating convention in Chicago when the convention deadlocked, the anti-Grant faction united around James A. Garfield, who was reluctant to become a candidate.

In the Democratic side, despite challenges from an impressive slate of contenders, Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, a Union commander during the Civil War and the respected military governor of Louisiana and Texas during Reconstruction, captured the nomination. Struck down by an assassin's bullet just one hundred days after his inauguration, Garfield had little time to achieve much. Guiteau, age thirty-nine at the time, was known around Washington as an emotionally disturbed man. He had killed Garfield because of the President's refusal to appoint him to a European consulship. In planning this violent act, Guiteau stalked Garfield for weeks. On the day Garfield died, Guiteau wrote to now President Chester A. Arthur, "My inspiration is a godsend to you and I presume that you appreciate it. . . . Never think of Garfield's removal as murder. It was an act of God, resulting from a political necessity for which he was responsible." At his trial, the jury deliberated one hour before returning a guilty verdict. Sentenced to be hanged, Guiteau climbed the scaffold on June 30, 1882, convinced that he had done God's work.

|

|

In the election of 1884, Cleveland appealed to middle-class voters of both parties as someone who would fight political corruption and big-money interests. Many people saw Cleveland's Republican opponent,

James G. Blaine, as a puppet of Wall Street and the powerful railroads.

When he ran for reelection in 1888, the Republicans raised lots of money from the nation's manufacturers and spent it lavishly, helping to ensure victory for their candidate, Benjamin Harrison. The election thus marked the beginning of a new era in campaign financing. Though Cleveland actually won a larger share of the popular vote, Harrison defeated Cleveland in the Electoral College.

In 1892, however, after four years of Republican leadership, Cleveland quashed the reelection hopes of Harrison, who had alienated many in his own party. He thus became the only President to serve nonconsecutive terms, winning the office once again after losing as the incumbent.

|

|

William Jennings Bryan's nomination at the Democratic convention in 1896 appeared to some as a spontaneous event fueled by his challenge against the British gold standard, in his "cross of gold" speech:

Therefore, we care not upon what lines the battle is fought. If they say

bimetallism is good, but that we cannot have it until other nations

help us, we reply that, instead of having a gold standard because

England has, we will restore bimetallism, and then let England have

bimetallism because the United States has it. If they dare to come out

in the open field and defend the gold standard as a good thing, we will

fight them to the uttermost. Having behind us the producing masses of

this nation and the world, supported by the commercial interests, the

laboring interests and the toilers everywhere, we will answer their

demand for a gold standard by saying to them: You shall not press down

upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify

mankind upon a cross of gold.

The gathering was electrified by his performance, but Bryan's handlers had long been at work securing votes from the delegates. He traveled thousands of miles by train and delivered hundreds of speeches, stopping even in the smallest of towns. His oratorical prowess earned him the nickname "boy orator of the Platte,"

Bryan's limited message was instrumental in his loss to William McKinley, an event that ushered in another era of Republican leadership. Under Bryan's influence, the Democratic party underwent a dramatic change. The earlier Jacksonian legacy was one dedicated to limited government, but the party from 1896 onward promoted a more expansive role.

|

|

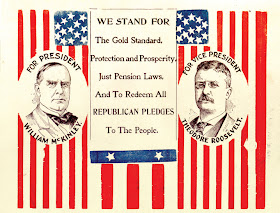

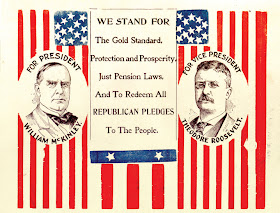

The devastating economic collapse of 1893 turned voters against the Democratic Party's hold on the presidency, giving McKinley a good shot at the White House in 1896. McKinley argued that his commitment to

protective tariffs on imported goods would cure unemployment and stimulate industrial growth.

McKinley's political ally from Ohio, the industrialist Marcus Hanna, helped McKinley organize and fund his campaign. McKinley beat Democrat William Jennings Bryan in the greatest electoral sweep in twenty-five years. Four years later,the popular McKinley ran on a strong record and defeated Bryan again, by even larger margins. |

|

McKinley led the U.S. into its first international war with a European power since the War of 1812. The decision to come to the aid of the Cubans struggling to throw off Spanish rule was hastened by reports that Spain was responsible for the explosion of the U.S. battleship Maine. After three short months of fighting, the U.S. was victorious. The peace treaty between the United States and Spain granted Cuba its independence—although the island became a U.S. protectorate—and gave the United States control of former Spanish colonies, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Further asserting American power on the global scene, McKinley sent 2,000 troops to China to help the Europeans put down the Boxer Rebellion. He also intervened twice in Nicaragua to protect U.S. property interests. Both of these actions were examples of the United States as a rising hemispheric and world colonial power. McKinley's difficult foreign policy decisions, helped the U.S. enter the twentieth century as a new and powerful empire on the world stage. |

|

Theodore Roosevelt, who came into office in 1901 and served until 1909,

is considered the first modern President because he significantly expanded the influence and power of the executive office. From the Civil War to the turn of the twentieth century, the seat of power in the national government resided in the U.S. Congress. Beginning in the 1880s, the executive branch gradually increased its power. Roosevelt seized on this trend, believing that the President had the right to use all powers except those that were specifically denied him to accomplish his goals. As a result, the President, rather than Congress or the political parties, became the center of the American political arena.

As President, Roosevelt worked to ensure that the government improved the lives of the citizens. His "Square Deal" domestic program reflected the progressive call to reform the American workplace, initiating welfare legislation and government regulation of industry. He was also the nation's first environmentalist President, setting aside nearly 200 million acres for national forests, reserves, and wildlife refuges.

In foreign policy, Roosevelt wanted to make the United States a global power by increasing its influence worldwide. He led the effort to secure rights to build the Panama Canal, one of the greatest engineering feats at that time. He also issued his "corollary" to the Monroe Doctrine, which established the United States as the "policeman" of the Western Hemisphere. In addition, he used his position as President to help negotiate peace agreements between belligerent nations, believing that the world should settle international disputes through diplomacy rather than war.

|

|

William Howard Taft tried to diminish the power of the imperial presidency. He believed in a conservative administration and disapproved presidential activism. Though he came to the White House promising to continue Roosevelt's agenda, he was more comfortable executing the existing law than demanding new legislation from Congress. His first effort as President was to lead Congress to lower tariffs, but traditional high tariff interests dominated Congress, and Taft largely failed in his effort at legislative leadership. He also alienated Roosevelt when he attempted to break up U.S. Steel, a trust that Roosevelt had approved while President. Taft also forced Roosevelt's forestry chief to resign, jeopardizing Roosevelt's gains in the conservation of natural resources.

By 1911, Taft was less active in "trust-busting," and generally seemed more conservative. In foreign affairs, Taft continued Roosevelt's goal of expanding U.S. foreign trade in South and Central America, as well as in Asia, and he termed his policy "dollar diplomacy." Taft so disappointed his predecessor, former mentor, and friend, that Roosevelt opposed his renomination in 1912 and bolted from the Republican Party to form his own "Bull-Moose" party, creating an opening for Democrat Woodrow Wilson

in the 1912 presidential election.

Taft's lifelong ambition was to serve as Chief Justice of the United States, to which he was appointed after leaving the presidency. He remains the only man in American history to have gained the highest executive and judicial positions. |

|

Woodrow Wilson was one of America's most activist Presidents. His domestic program expanded the role of the federal government in managing the economy and protecting the interests of citizens. His foreign policy

established a new vision of America's role in the world. And he helped to make the White House the center of power in Washington.

Wilson's New Freedom platform called for tariff reduction, reform of the banking and monetary system, and new laws to weaken abusive corporations and restore economic competition. With a Presbyterian's confidence that God was guiding his course, Wilson pursued his New Freedom agenda with the zeal of an evangelical crusader, making use of his skill as an orator to galvanize the nation in support of his policies. Perhaps his most consequential achievement was the passage of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913, which created the system that still provides the framework for regulating the nation's banks, credit, and money supply today. Other Wilson-backed legislation put new controls on big business and supported unions to ensure fair treatment of working Americans.

In foreign affairs, Wilson administration intervened militarily more often in Latin America than any of his predecessors. In the European war, American neutrality ended when the Germans refused to suspend submarine warfare after 120 Americans were killed aboard the British liner Lusitania and a secret German offer of a military alliance with Mexico against the United States was uncovered. In January 1918, Wilson made a major speech to Congress in which he laid out "Fourteen Points" that he believed would, if made the basis of a postwar peace, prevent future wars. Trade restrictions and secret alliances would be abolished, armaments would be curtailed, colonies and the national states that made up the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires would be set on the road to independence, the German-occupied portions of France and Belgium would be evacuated, the revolutionary government of Russia would be welcomed into the community of nations, and a League of Nations would be created to maintain the peace.

Believing that this revolutionary program required his personal support, Wilson decided that he would lead the American peace delegation to Paris, becoming the first President ever to go to Europe while in office. Despite Wilson's best efforts, however, the Treaty of Versailles, signed in June 1919, departed significantly from the Fourteen Points, leaving both the Germans and many Americans bitterly disillusioned.

|

A conservative politician from Ohio, Warren G. Harding tried to restore Howard Taft's policy of diminishing the power of the imperial presidency, after Woodrow Wilson, America's most activist President, had inflated the role of government and the President. Harding understood that Americans detest the big and intrusive government, and sensing the nation's fatigue with the activist agenda of Woodrow Wilson,Ran with the slogan, "A Return to Normalcy," The electorate responded favorably and Harding beat progressive Democrat James M. Cox in a massive landslide.

Decidedly conservative on trade and economic issues, Harding favored pro-business government policies, allowing Andrew Mellon to push through tax cuts for the entrepreneur, stopping anti-business actions, and opposed rigidities introduced in the labour markets by organized labor. As for foreign affairs, Harding administration used the Fordney-McCumber Tariff to secure oil markets in the Middle East, especially in modern-day Iraq and Iran, and revised Germany's war debts downward through legislation, passed in 1923, known as the Dawes Plan. Harding also called for a naval conference with nine other nations to freeze naval spending in an effort to reduce spending.

After becoming ill with what was at the time attributed to ptomaine (food) poisoning, Harding had a heart attack and died quietly in his sleep.

In an intensely emotional speech in the 1948 Democratic Convention, Hubert Humphrey, mayor of Minneapolis and a candidate for Senate, argued that "The time is now arrived in America for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states' rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights." On July 14, the last day of the convention, the liberals won a close vote. The entire Mississippi delegation and half the Alabama contingent walked out of the convention. The rest of

the South would back Senator Richard B. Russell of Georgia as a protest candidate against Truman for the presidential nomination.

Nearly two weeks after the convention, the president issued executive orders mandating equal opportunity in the armed forces and in the federal civil service. Outraged segregationists moved ahead with the formation of a States' Rights ("Dixiecrat") Party with Gov. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina as its presidential candidate. The States' Rights Party avoided outright race baiting, but everyone understood that it was motivated by more than abstract constitutional principles.

|

| Early in 1952, while Adlai Stevenson was still governor of Illinois, President Harry S. Truman proposed that he seek the Democratic nomination for president. In a fashion that was to become his trademark, Stevenson at first hesitated, arguing that he was committed to running for a second gubernatorial term. Despite his protestations, the delegates drafted him, and he accepted the nomination at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago with a speech that according to contemporaries, "electrified the nation." He chose John J. Sparkman, an Alabama senator, as his running mate. Stevenson's distinctive speaking style quickly earned him the reputation of an intellectual and endeared him to many Americans, while simultaneously alienating him from others. His Republican opponent, enormously popular World War II hero General Dwight D. Eisenhower, defeated Stevenson. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

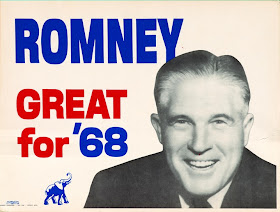

It has been argued that an American election is no game for men of little means and weak connections, as running for president of the United States is, in fact, a game for millionaires like President Obama and his rival, Mitt Romney, who are both Harvard educated millionaires.

However, I am sure that election posters are a great equalizer in this game and have become the most potent medium of political mass communication in the brave new age of Twitter, and a drastic shortening of the general attention span of electorates. I don't think that the first priority of a candidate is or should be to attract wealthy donors and fund-raisers to underwrite his or her campaign. To me the first priority should be to attract the talented graphic designers to a cause.

Here are some of the pro and against Romney-Ryan ticket posters .

French Presidential Campaigns

b

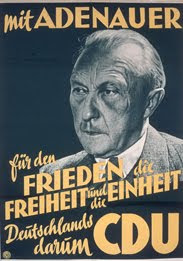

German Election Campaigns

|

| "No experiments!" Konrad Adenauer on a 1957 election campaign poster. |

|

Ludwig Erhard.

Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 1965 |

|

| So tomorrow you can live in peace, Foreign Minister Willy Brandt, Federal Republic of Germany, 1969 |

|

| German, we can be proud of our country, Elect Willy Brandt |

|

The better man must remain chancellor, Helmut Schmidt. Therefore, SPD,

SPD poster for the 1976 election |

|

| Foreign Minister, Domestic Green; Joschka Fischer |

|

I am ready,

|

|

| A new beginning, ,Angela Merkel , CDU |

|

| For Peace: Against Blindly Following, Gerhard Schröder, SPD |

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment