Although a great number of petroglyphs have been identified in Iran, only a few rock painting sites have been found. Despite this, a considerable number of rock paintings have been discovered in Kuh-e-Donbeh, which is a mountain located to the southwest of the city of Esfahan in central Iran. The paintings can be found on the rims of seasonal water channels on this mountain. All the depictions are painted with red pigment sourced from the immediate region. The motifs depicted include zoomorphs, anthropomorphs, horse-riding scenes, and some unknown shapes, etc. A farming theme is also prevalent in the corpus. The paintings are located in five areas and, in some cases, have been subject to intense weathering.

As a manifestation of socio-cultural evolution, the emergence of graphic design, sculpted or painted on the surface of rocks, has played a key role in the history of Homo sapiens as a social being, and thus, the history of graphic design must encompass all the memory of human visual communications.Several hundred stylized compositions of animals by the primitive artists of the Chauvet cave, in the south of France, which were drawn even before 30,000 BC, the image of "Spotted Horses", painted by woman artists, inside France's Pech Merle cave dated 23,000 BC, as well as similar designs in the Lascaux cave of France, that were drawn more than 14,000 B.C., the Altamira cave paintings of bison from between 9,000 and 17,000 BC, drawings of primitive hunters in the Bhimbetka rock shelters in India which were drawn over 7,000 BC, Aboriginal rock art, in Kakadu National Park in Australia, and many other carved rock or rock paintings in other parts of the world bear witness to the very long history of the culture of visual communication shared by humanity.

The rock art refers to a very ancient form of visual communication. This art form includes painted, drawn, and sculpted works found on rock formations of all kinds: caves, rock shelters, and open-air boulders or rock outcrops. The term cave art is used to identify art in enclosed spaces. Found on five continents, rock art sites are among the most widespread cultural phenomena of humanity. They have stood the test of time and many can be seen to this day.

The act of creating rock art involved considerable costs for the artist in terms of time and energy spent collecting all the necessary materials, such as pigments and lighting torches, which were very demanding and required considerable effort both for their collection and for their subsequent preparation. In addition, the paintings made deep in the caves also imposed an element of risk with the need to negotiate dangerous routes through the cave systems. The acceptance of these costs by the ancient pioneer artists seems to indicate that the motivation to produce rock art was strong.

The materials and methods used to produce cave art were varied, and artists used a range of colors to create naturalistic representations. The simplest and most accessible material to mark a cave wall was to use charcoal from the remnants of fires and a large percentage of the rock art produced was drawn this way. Among the pigments used for painting, ocher was a popular choice because this substance has long been used by early humans - perhaps for body art, but it has many uses, including medicinal qualities that make it suitable for healing wounds. Manganese and iron oxides have also been used as pigments, to produce black and red, respectively. Interestingly, almost all cave paintings were drawn in these two colors - although artists also had access to yellow and white colors, these were rarely used. The pigments often came from places several kilometres from where the caves were located.

In the process of creating cave paintings, artists would have spent considerable amount of time inside the deepest caves and therefore needed some form of lighting. The simplest form of lighting was to use a piece of burning wood like a torch. As the torches burned, they were often wiped against the walls to remove excess charcoal. Such telltale marks have been found in many caves and have been used in radiocarbon dating. But the problem with torches was that they didn't last too long, so the main source of light were lamps that used animal fat or tallow fuel and a wick often made of lichen, juniper, or grass. The fuel could either be cut directly from the animal (for example, the kidney cavity of an ox) or come from the bone marrow. The lamps were made of pieces of stone with a handle on one end and a wider, ground out area, at the other end. More than a hundred of these lamps were found in the Lascaux cave, many on the ground directly under the paintings.

|

The "Spotted Horses" mural, painted by woman artists inside France's Pech Merle cave dated 23 millennium BC is a fine example of the prehistoric graphic design. According to the analysis of Pennsylvania State University archaeologist Dean Snow many of the artists working in that cave were women. Until recently, most scientists assumed the prehistoric handprints on the rockwalls around such images belong to man.National Geographic |

|

| The image of a bison in Altamira Cave, Spain. |

|

| Image of a horse in the Chauvet cave. |

|

| Drawing of a horse in the Lascaux cave. |

|

| A rock drawing in Bhimbetka India. |

|

| Aboriginal Rock Art, Ubirr Art Site, Kakadu National Park, Australia |

|

| A battle image on Tassili rocks of Ajjer (Algeria), |

A good example of this art is observable on the paintings of Altamira, which are located in the deep recesses of caves in the mountains of Northern Spain, far out of the reach of the destructive forces of wind and water. As a result these paintings have been preserved rather intact from 9,000-17,000 B.C. In addition to these murals, Altamira is the only site of cave paintings in which tools, hearths and food remains also have been found. These signs shed light on the habitat, and living conditions of these prehistoric artists . Unlike the other similar caves in Europe and elsewhere, the Altamira caves show no signs of soot deposits, which perhaps suggest that the people at Altamira had slightly more advanced lighting technology emitting less smoke and soot than the torches and fat lamps which Paleolithic people are given credit for.

It should be noted that, there is no consensus among archaeologists as to when Altamira's parietal art was first created. Early investigations suggested that the most of it was created at the same time as the Lascaux cave paintings - that is, during the early period of Magdalenian art (15,000 BC). But according to the most recent research, some drawings were made between 23,000 and 34,000 BCE, during the period of Aurignacian art, contemporaneous with the Chauvet Cave paintings and the Pech-Merle cave paintings. The general style at Altamira remains that of Franco-Cantabrian cave art, as characterised by the pronounced realism of the figures represented. Indeed, Altamira's artists are renowned for how they used the natural contours of the cave to make their animal figures seem extra-real.

Like the Lascaux cave, Altamira has three types of art: coloured paintings, black drawings and rock engravings. As mentioned above, subjects are mostly animals (bison, boar, deer, horses), although there are eight anthropomorphic figures and a large amount of geometric signs and symbols.

The paintings are unique for several reasons. First, they are composed of many different colours (up to three colours in a single animal), more than is common in most other examples of parietal art. The bisons in particular are depicted in varying shades, making them appear astonishingly lifelike. Second, the animals - twenty-five of which are depicted in life-size proportions - are depicted with unusual accuracy. The bisons are especially well rendered; so too is the red deer. Other animals are also depicted in detail, down to the texture of their fur and manes. Third, when composing their pictures, the Magdalenian artists took full advantage of the natural contours, facets and angles of the rock surface to make the figures as three-dimensional as possible.

The Altamiran artists primarily focused on bison, which was a main economic resource for them. Not only as a source of food, but also other useful commodities like skin, bones and fur. These prehistoric artists used natural earth pigments like ochre and zinc oxides, some of the images are painted with three colors. This is a significant artistic achievement, particularly when taken into consideration the masterly execution of the animal's anatomy, and their accurate physical proportions.

|

On the 18th December 1994, three French cavers - Eliette Brunel-Deschamps, Christian Hillaire and Jean-Marie Chauvet discovered the Chauvet cave with breathtaking Palaeolithic period paintings which are about 35,000 years old. |

|

The paintings of the Chauvet cave depict a stunning menagerie of the beasts that roamed Ice Age Europe 35,000 years ago. |

|

Painted in charcoal and red ochre, or etched into the limestone, the artists worked with the contours of the rock with careful shading and skilful technique to bring more than 400 animals to life, revealing movement and depth.

|

|

Paintings are not the only traces of the human presence: as the soil remained untouched, twenty footprints of a preteen, fireplaces and flint tools with traces of use are also present.

|

Before adopting a sedentary lifestyle, nomadic groups, like other living creatures, spent most of their lives foraging for food. Our ancient ancestors were much less isolated from nature than we are today. Unlike us who tend to move away from animals by creating urban centers, they have cohabited with them. In 1863-64, the French geologist Édouard Lartet and his friends Henry Christy excavated a number of caves and rock shelters at Cro-Magnon near the town of Eyzies-de-Tayac in the Dordogne in the southwest of France, where they found a number of ancient human skeletons. It was during their excavations at La Madeleine that the engraved drawing of a mammoth on mammoth ivory was found, accompanied by stone tools. Stone tool technology is one of the most durable and studied materials reflecting prehistoric human culture. This observation can be considered as proof that graphic art appeared even before the emergence of agriculture and a sedentary lifestyle. Geologists have discovered five archaeological layers, where human bones have been found in the top layer that could be dated 10,000 to 35,000 years old.

The prehistoric humans identified by this discovery were called Cro-Magnons and have since been considered, along with the Neanderthals, to be representative of prehistoric humans. Modern studies suggest that Cro-Magnon appeared even earlier, perhaps 45,000 years ago. Cro-Magnons were robustly built and powerful and are presumed to have been about 166 to 171 cm tall. The body was generally heavy and solid, apparently with strong musculature. The forehead was straight, with slight browridges, and the face short and wide. Cro-Magnons were the first humans (genus Homo) to have a prominent chin. The brain capacity was about 1,600 cubic centimeter, somewhat larger than the average for modern humans. It is thought that Cro-Magnons were probably fairly tall compared with other early human species.

Instead of avoiding Chauvet Cave, a potentially dangerous place, it appears that these early humans embraced their affinity with animals and ventured into caves where predators had sought refuge. Although they had recognized the spiritual significance of the cave, they also respected that space as the domain of the cave bears. Thus, they never used this space as a shelter, but employed it only for painting and possibly for their ritual ceremonies. Instead of trying to subjugate the cave bears or occupying their place, they used the space only in special occasion.

The subjects of these paintings bear witness to the admiration that artists felt for the beauty of animals in their ecological environment. These early artists demonstrated their respect for the animals by being meticulously faithful to their anatomical detail. In fact, their art exhibits an intimate knowledge of the animal world, as is evident by their ability to accurately represent not only the appearance of animals but also their behaviors. In Chauvet, there are paintings of multiple horses shown with their mouths open giving the impression they are whinnying, rhinos fighting with legs jutting forward and horns colliding, and a male lion courting a female who is "raising her lips [and] baring her teeth." What is amazing about these pieces are the sensory response they trigger in the viewer. The viewer is able to hear the whinnies, the clashing of the horns, and the harsh growl. More importantly, the viewer feels the emotions of the animal and can understand their story. To have such a penchant for relating these stories, artists must have a strong connection to these animals, which has helped them develop a powerful visual communication grammar - a grammar that will be discussed throughout this book. In order to properly describe these stories, he or she must have been able to empathize with the animals and understand their emotions. By sympathizing with animals, they saw themselves as part of this animal kingdom, not necessarily dominant over it.

Petroglyphs and Pictographs

Rock art has been divided into several categories:

I. Lichenoglyphs are created by scratching the surface of a rock covered with lichen to create, by contrast, a more or less complex pattern;

ii. Sgraffito are patterns produced on the surface of a rock by removing the top layer to reveal the contrasting layer below. These patterns are usually in lighter shades, as the rock surface acquires a darker patina over time;

iii. Petroforms are rocks arranged in lines or circles on the ground, or stacked on top of each other - like an Inuit inukshuk - to form a figure. Petroforms have several purposes: practical or linked to the cosmology of the groups that created them;

iv. Geoglyphs are large geometric or figurative patterns created by removing the surface of the ground to produce a contrasting pattern with the layer below.

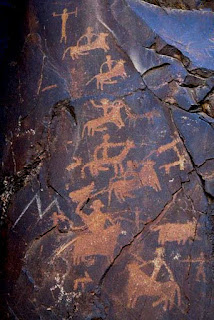

In general, Petroglyphs, carved or pecked into stone, are the most common form of rock art remaining in Nevada, Scandinavia, and Canada. Early artists sometimes chose a stone covered with a dark surface called desert varnish (or patina) and carved through the surface, creating an image in the lighter colored rock beneath. While desert varnish has covered the images, the original marks are still visible. Pictographs were painted onto the surfaces with red, yellow, and sometimes green pigments made from minerals or plants and other organic material. Over thousands of years, water, wind, and even people have washed away or damaged much of the paint, leaving only faint traces of some of these paintings.

Rock Art in the Aïr Mountains of the Sahara

In the heart of the Sahara is the Ténéré desert. 'Tenere', literally translated as 'where there is nothing', is a barren desert landscape stretching for thousands of miles, but this literal translation belies its ancient meaning - for over two millennia the Tuareg operated the trans-Saharan caravan trade route linking major cities on the southern edge of the Sahara via five desert trade routes to the northern coast of Africa.

Life in the region now known as the Sahara has evolved over millennia, in various forms. A particular piece of evidence of this centuries-old occupation can be found atop a solitary rock outcrop. Here, where the desert meets the slopes of the Aïr Mountains, lies Dabous, home to one of the finest examples of ancient rock art in the world - two life-size giraffes carved in stone. They were first recorded in 1987 by Christian Dupuy. A subsequent field trip organized by David Coulson of the Trust for African Rock Art, caught the attention of archaeologist Dr Jean Clottes, who was surprised at their significance, due to their size, beauty, and technicality.

The two giraffes, a large male in front of a smaller female, were etched side by side on the weathered surface of the sandstone. The larger of the two stands over 18 feet tall, combining several techniques including scraping, smoothing, and deep contour engraving. However, signs of deterioration were clearly evident. Despite their remoteness, the site began to receive more and more attention, as these exceptional engravings began to suffer the consequences of voluntary and involuntary human degradation. The petroglyphs were damaged by trampling, but perhaps worse than that, they were defaced by graffiti, and fragments were stolen.Under the auspices of UNESCO, the Bradshaw Foundation was tasked with coordinating the Dabous preservation project, in association with the Trust for African Rock Art.

Wanjina Style of Kimberley Region of Western Australia

Aboriginal people in northern and central Kimberley region of Western Australia continue to identify with Wanjina, a continuous tradition dating to the last 4000 years. As figurations of supernatural power, images of Wanjina are characterised by halo-like headdresses and mouthless faces with large round eyes, set either side of an ovate nose. These ‘Creator Beings’ and the ‘Wunggurr Creator Snake’ are painted in many forms and can be repainted to ensure annual renewal of the seasonal cycle and the associated periods of natural fertility. The actual Wanjina is believed to either reside in the rock where it is painted or to have left its body there.

|

Kimberley region of Western Australia is one of the world’s oldest and richest rock art regions. Two major traditions of rock art are seen in the Kimberley - Gwion Gwion Bradshaw figures and Wandjina rock art. Claimed to be some of the earliest figurative art, the Gwion Gwion or Gyorn Gyorn paintings were first seen by European eyes in the late 1890’s. Their distinguishing feature is the stick-like human figures, often depicted with adornments of tassels or sashes. |

|

The land of the Wunambal Gaambera people, which unfurls over 6.17 million acres (2.5 million hectares) in the north Kimberley, is home to tranquil Swift Bay, or Warrabii West. “Two sites at Swift Bay are close together but depict totally different styles,” says Silversea guest lecturer Tim Harvey. “One site contains mostly Gwion figures. The other, more recent site, has large Wandjina figures on the ceiling, as well as numerous fish, ducks, turtles and crocodiles.”

According to Harvey, this location is the perfect place to compare the two principal Kimberley rock art styles, which are Wandjina and Gwion (also called Bradshaw) art. The large, wide-eyed Wandjinas are spirit figures drawn on thousands of cliffs and cave walls in the Kimberley.

|

|

The Wandjina is highly revered as the Supreme Being spirit for the Worrora, Ngarinyin and Wunumbal tribes in the Kimberley. These language groups make up the Mowanjum Community located 15km outside of Derby. The artists at the Mowanjum Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre depict Wandjina and Gyorn Gyorn figures based on the cave paintings central to their culture. |

|

Researchers who study Aboriginal rock art face a significant challenge— definitively dating these pieces. From 2013 until 2016, Dr. June Ross from the University of New England, Dr. Kira Westaway from Macquarie University, together with her colleagues and Aboriginal community members, analyzed art in over 200 sites in the northwest Kimberley.

|

Rock Art of Bi’r Hima in Saudi Arabia

Bi’r Hima, located in southwestern Saudi Arabia, stands as an archaeological marvel, housing one of the world's most significant collections of ancient rock art and inscriptions. Dating back as far as 7,000 years, this site provides a unique glimpse into the lives, beliefs, and survival strategies of ancient Arabian communities. The thousands of petroglyphs found here depict various elements of daily life, including representations of camels, ostriches, and even extinct species such as lions and ibexes, suggesting that the region once supported a more fertile environment.

Historians posit that Bi’r Hima served as a critical junction along ancient trade routes, where caravans transporting incense, spices, and valuable goods from southern Arabia to the Mediterranean likely paused. The inscriptions, which include early scripts such as Musnad and Aramaic-Nabatean, indicate the site's role as a cultural crossroads, influenced by South Arabian, Nabatean, and early Arabic traditions. Furthermore, some scholars suggest that Bi’r Hima functioned as a meeting ground for diverse tribes and travelers, with carvings that may commemorate agreements, rituals, or shared legends, thereby reflecting the complex interactions among different groups across time and space.

Rock Art in Game Pass Shelter, South Africa

Polychrome paintings of elands and human characters on the Game Pass site, located in the Drakensberg mountains, in the province of Kwazulu-Natal South Africa.

High in a secluded valley in the Drakensberg Mountains sits the spectacular Game Pass site. Here, on the walls of a narrow sandstone shelter, are painted numerous images of eland (the largest of all antelopes). For a shelter so open to the elements, the paintings are miraculously well preserved and in some places the brush marks are still visible. Among the many images of eland are smaller human figures in running postures. This site, however, is best known for a group of images tucked away on one side of the shelter. It was an in-depth analysis of these images that first led researchers to realize that art was a system of metaphors closely associated with San shamanic religion.

Rock Art in Scandinavia

|

The Petroglyphs in Tanum, located in the northern part of Bohuslän province in western Sweden (Västra Götaland County), are a unique artistic achievement for their rich and varied motifs (depictions of humans and animals, weapons, boats, and other symbols) and for the cultural and chronological unity they express. They reveal the life and beliefs of people living in the Nordic region of Bronze Age Europe, and are remarkable for their large numbers and outstanding quality. A cultural landscape with a continuity in settlement and consistency in land use that spans more than eight millennia, the area is rendered outstanding by its assemblage of Bronze Age rock art. |

|

Ships were a very frequent motif in the South Scandinavian Bronze Age. There are thousands of petroglyphs depicting ships and they are a common motif on bronze razor knifes, of which also many have been found. For example, half of Bornholm's petroglyphs depict ships.

Flemming Kaul has analyzed ship images on Danish bronze objects and found that 97 ships are sailing to the right while only 26 of the ships are sailing left. By comparing with the sun chariot and the sun's path in the sky, seen to the south, we can conclude that the 97 ships are sailing to the west and the 26 against east. The motives that are attached to the respective right and left sailing ships are different, indicating that the sailing direction is not random. As many as 41 of the right-sailing ships have attached circles, which can be interpreted as sun symbols, while not a single ship sailing to the left is attached with sun symbols. |

|

There are more questions than there are answers about the symbolism of the petroglyphs. We do not know why they were made, but many historians believe that the figures can be linked to religious practices, such as sun worship or fertility wishes for animals and humans. it is common to talk about two groups of rock carvings in Norway, and also in the rest of the Scandinavian countries for that matter. The oldest group is often called veideristninger (rock engravings) because motives are associated with hunting cultures. These engravings are sometimes also called stone age engravings because many archaeologists consider them to have been made during the Stone Age.

Rock Art in North America

|

|

Anasazi and other Native American groups in Nevada came over 8,000 years ago and created a lasting legacy in rock art images carved or painted on stone surfaces. While we do not know what many of the images mean, native people living in Nevada today have traditional stories that incorporate some of the images or scenes. |

|

The gleaming white limestone slab at Peterborough, carved by the native Algonquin and other First Nations peoples between 900 and 1400 AD resemble ancient art found in Scandinavia. Additionally, two images closely resemble the hunchback figure of a Hopi kachina flute player named Kokopelli and may be attributable to ancient migrating Hopi travelers. This is the largest known concentration of Aboriginal rock carvings in Canada (and probably North America) with over 900 petroglyphs. Over 300 of the carvings are very distinct and depict turtles, snakes, birds, humans and other images including the figure of the Algonquin shamen, carved into crystalline limestone.

According to indigenous legends this is an entrance into the spirit world and that the Spirits actually speak to natives from this location. They call it Kinoomaagewaapkong, which translates to "the rocks that teach".

The petroglyphs are carved into a single slab of crystalline limestone which is 55 metres long and 30 metres wide. About 300 of the images are decipherable shapes, including humans, shamans, animals, solar symbols, geometric shapes and boats.

It is generally believed that the indigenous Algonkian people carved the petroglyphs between 900 and 1400 AD. But rock art is usually impossible to date accurately for lack of any carbon material and dating artefacts or relics found in proximity to the site only reveals information about the last people to be there. They could be thousands of years older than experts allow, if only because the extensive weathering of some of the glyphs implies more than 1,000 years of exposure.

There are some other mysteries surrounding these remarkable petroglyphs. The boat carvings bear no resemblance to the traditional boat of the Native Americans. One solar boat — a stylized shaman vessel with a long mast surmounted by the sun — is typical of petroglyphs found in northern Russia and Scandanavia. A Harvard professor believes the petroglyphs are inscriptions (and maybe even a form of written language) left by a Norse king named Woden-lithi, who was believed to have sailed from Norway down the St. Lawrence River in about 1700 B.C., long before the Greenland Viking explorations.

|

|

Mishipeshu and other pictographs at Agawa Bay – said by Thor Conway to be “the most famous image of aboriginal art in Canada”

|

Rock Art in Iran

Iran's rock art sites are spread across the country at Birjand (Lakh mazar), Khorasan (Nehbandan), Yazd (Arnan), Sistan and Balochistan (Nikshahr and Saravan), Isfahan (Gharghab and Kucherey at Golpaygan and Vist in Khansar), Lorestan (Homiyan in Kuhdasht, Khommeh in Aligudars, Mihad in Borujerd), Arak (Ibrahim Abad, Yasavel in Komijan, Ahmadabad in Khondab and Khomein), Hamadan (Darre Shahrestaneh Alvand, Darreh Ganjistan (Sarcenameal and) Khosrabayer Deh), village of Dowlatabad, Sharyar, Kuhe (Kaftarlu) and Qum (Kahak) In the Khomein region, there are several thousand rock art sites.

Much of Iranian rock art consists of the ibex motif, which is believed to have been a source of meat and secondary products such as horn and skin for prehistoric peoples. Archaeological evidence shows that it was hunted in Iran from the Middle Paleolithic onward, at the sites of Warwasi and the Yāfte cave (c. 38,000-29,000 BC). Studies of horn cores from the early Neolithic sites of Tappe ʿAli Koš and Tappe Sabz indicate that ibex were hunted at the end of the 8th and 7th millennia BC.

In Tassili-n-Ajjer in Algeria, one of the most famous of North African sites of rock painting, various images depict a historical evolution. This historical documentation of mankind evolution is something that graphic design has always done, and will do so in future. Tassili paintings depict at least four distinct chronological periods, which are: an archaic tradition depicting wild animals whose antiquity is unknown but certainly goes back well before 4500 B.C.; a so-called bovidian tradition, which corresponds to the arrival of cattle in North Africa between 4500 and 4000 B.C.; a "horse" tradition, which corresponds to the appearance of horses in the North African archaeological record from about 2000 B.C. onward; and a "camel" tradition, which emerges around the time of Christ when these animals first appear in North Africa.

Rock Art of the Amazonian Rainforest

Archaeologists have found tens of thousands of paintings of animals and humans created up to 12,500 years ago across cliff faces that stretch across nearly eight miles in Colombia. The site is in the Serranía de la Lindosa, and the Chiribiquete national park. The paintings are estimated to have been made between 11,800 and 12,600 years ago, towards the end of the last Ice Age. Their date is based partly on their depictions of now-extinct ice age animals, such as the mastodon, a prehistoric relative of the elephant that hasn’t roamed South America for at least 12,000 years. There are also images of the palaeolama, an extinct camelid, as well as giant sloths and ice age horses.

The paintings vary in size. There are numerous handprints and many of the images are on that scale, be they geometric shapes, animals or humans. Others are much larger. For Amazonian people, non-humans like animals and plants have souls, and they communicate and engage with people in cooperative or hostile ways through the rituals and shamanic practices that we see depicted in the rock art. This is perhaps why the imagery includes trees and hallucinogenic plants and many of the large animals are surrounded by small men with their arms raised, which apparently they are worshipping the animals.

The Petroglyphs of Indus Valley

High in the Indus Valley of Pakistan are some of the most intricate and diverse petroglyphs on earth. These are the ancient Shatial glyphs on the Karakoram Highway in the Giligit-Baltistan region. Dating from the Stone Age to the birth of Islam, the glyphs cover rocks and boulders stretching for over 100 kilometers. The writings and designs cover several languages, religions and the symbolism of peoples dating back 10,000 years. Some of these magnificent glyphs are under threat from modern hydropower projects planned in the Indus Valley.

The Wall Paintings at Zimri-Lim's Palace

It is evident that with the process of human development and the emergence of civilization triggered by urban settlements, rock art and cave painting evolved into mural art.The town of Mari is located on the Middle Euphrates, an important place for river trade provides an early example of mural art. Mary in its history has drifted in and out of the orbit of Mesopotamian influence. It was destroyed by Sargon or Naram-Sin during the Akkadian dynasty and then again by Hammurabi despite the fact that Zimri-Lim supported the troops of the Babylonian king Mariote during his conflict with the Elamites of Iran . The city was eventually destroyed by Hammurabi of Babylon around 1760 BC. The palace was so large that Hammurabi claims it took him 2 years to completely plunder it, and it was remarkable even in ancient times - a letter to Zimri-Lim from another king states "Show me Zimri-Lim palace! I want to see it !"

After its looting by Hammurabi, Babylonian soldiers set the remains on fire, but despite this, more than 20,000 texts from the palace archives and fragments of several wall paintings were discovered during the excavations. While the palace is almost empty of furniture and decorative vases, the walls were covered with paintings that could not be removed by the looters. Some of these paintings have been found in situ on the walls, while others have been found in small fragments on the floors. The paintings were in varying states of preservation, sometimes only as fragments requiring extensive reconstruction, and sometimes as more complete scenes. Various visual communication scenes were featured, including cult / religious scenes, and possibly political and military narratives as well.

Scenes include sacrifices, mountainous terrain, and the so-called “investiture scene”, which remained on the wall in fairly good condition. Set in an otherworldly fantasy environment (represented by the composite animals flanking the main activity), the scene shows the king standing in front of the goddess Ishtar, who stands on a lion and presents him with a rod and ring, symbols of royalty. The figures at the bottom are goddesses holding flowing vases and are comparable to a statue found in an adjacent room that appears to have been an actual fountain.

The so-called "Investiture Scene" wall painting from the palace of Zimri Lim.

|

| Priest Guiding a Sacrificial Bull- Fragment of mural painting from the palace of Zimri-Lim, Mari (modern Tell Hariri, Iraq) 2040-1870 BC. |

The Inception of Visual Communications in Ancient Egypt

There is no doubt that ancient Egyptians were the originator of what is today defined as 'visual communication design'. The Egyptian language of antiquity used the same word, sekh, to signify writing, drawing, and painting, and from the very beginning of her history, Egypt used written messages in combination with images to convey various socio-cultural values that were at the roots of her system of beliefs. More than five thousand years ago, the graphic designers of Egypt were working on a strict greed system that established conventional codes of representation in sculpture, painting, and relief. By and large, Egyptian scribes used the same conventions in the standardization of hieroglyphic signs in their system of writing. This is why the ancient Egyptian graphic design and hieroglyphs are closely correlated. For instance, the hieroglyphic ideogram for "man," is the figure of a seated man, which also appears frequently in sculptures and paintings.

A topless dancer with elaborate hairstyle and hoop earrings in gymnastic backbend on a limestone ostracon, from Deir el-Medina; New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1200 BC.

Wooden ushabti box and ushabtis of Pinedjem I.

The composition of the Egyptian designs are well balanced, harmonious, and adhere to certain minimalism principles. The artists abstract from play of light and shadow, and minimalize the illusion of space and atmosphere in outdoor scenes. The images are sharpened by clear outlines, and the complexity of interrelationships among spatial forms are simplified. The artists use flat areas of color to enhance order and clarity, and compose figurative scenes in horizontal registers. The figures were portrayed emotionless since artists wanted to avoid the transient aspect of life, as they were interested in eternal features and immortality.

|

The Gods Osiris and Atum, from the Tomb of Nefertari, New Kingdom (wall painting), Egyptian 19th Dynasty (c.1297-1185 BC) / Valley of the Queens, Thebes

Egyptian gods are depicted wearing headdresses with a solar disk. Ostrich feathers, and animal horns. Usually the deities hold an ankh and a scepter. When in human form, the gods are shown wearing a false beard with a curved tip.

|

The Visual Communications and the Egyptian System of Beliefs

“Greetings to you, Osiris, Lord of Eternity

King of the Two Lands, Chief of both banks…<

Youth, King, who took the White Crown for himself…

Who makes himself young again a million times…

What he loves is that every face looks up to him…

Shining youth, who is in the primordial water, born on the first of the year…

From the outflow of his limbs both lands drink.

Of him it is arranged that the corn springs forth from the water

In which he is situated….

In the Egyptian system of beliefs Gods, such as Atum and Osiris, as well as many others, played the key roles in the management of universe and all its affairs. Not only they symbolized all natural phenomena but also abstract concepts such as truth, justice, kinship, and love.

|

Geb, the earth god is reclining beneath Nut, the sky goddess, while Shu, the air god, is preventing her from falling, and two ram-headed Heh deities, are supporting Shu's arms, Detail from the Greenfield Papyrus, from the Book of the Dead of Nesitanebtashru, c. 950 BC. |

In a dialogue between Atum and Osiris in the Book of the Dead, Atum states that he will eventually destroy the world, submerging gods, men and Egypt back into Nun, the primal waters, which were all that existed at the beginning of time. In this nonexistence, Atum and Osiris will survive in the form of serpents.

Atum’s myth merged with that of the great sun god Ra, giving rise to the deity Atum-Ra. In the beginning there was only Nun, a primordial mass of unstructured water, Atum-Ra, lived in Nun. After a period of time he rose from the splendor of the Sun. Atum-Ra was the father of the gods, creating the first divine couple, Tefnut and Shu, the first female and male gods. He created these two children out of dust and his own spittle; Tefnut, was the Goddess of Moisture, and Shu was the god of Air and together with their father they formed a trinity. Tefnut and Shu, gave birth to Geb, the earth God, who married Nut, the Goddess of sky, and with her fathered four children; Osiris, Isis, Seth and Nephthys.

|

| Judgement before Osiris, from the papyrus of the scribe Hunefer, from the book of the dead of Hunefer, 19th Dynasty. 1285 BC, painted papyrus, British Museum, London |

Osiris was the ruler of the underworld. The oldest and simplest hieroglyphic form of his name is written by a "throne" and an "eye." He was the eldest offspring of Geb, the god of Earth and Nut, the goddess of sky. He married Isis, who the Book of the Dead describes as "She who gives birth to heaven and earth, knows the orphan, knows the widow, seeks justice for the poor, and shelter for the weak". Osiris and his wife Isis became the king and the queen of Egypt when his father, Geb, retired. Osiris promulgated just and fine laws for his people who were considered privileged among the mankind. Osiris then asked Isis to assume the throne of Egypt and himself traveled afar to spread his laws around the world.

When Osiris returned, Seth, his jealous brother, plotted to murder him in order to usurp his throne. Seth gave a royal banquet and offered his guests, including Osiris, a prize in the form of a magnificent coffin, which was specially built to fit Osiris’ body. The winer was supposed to be the one who best fitted in the coffin, and when Osiris tried it, Seth shut the lid and threw the coffin in the Nile river. Seth assumed the kingship, and the grieving Isis went out to look for Osiris' body, where she found it in Byblos. She brought the corpse back to Egypt, and through her powerful magic brought him back to life for a while to conceive a son, Horus, who was to avenge his father's death. Seth found the Osiris body, tore it apart into pieces, and threw them back into the Nile. Isis stubbornly searched for him and found every piece of his body and reassembled it by papyrus bands into a mummy. Osiris then transformed to an akh, and traveled to the underworld to become king and judge of the dead.

Meanwhile, Seth continued his cruel rule. Isis was hidden with her baby Horus in the marshes. When Isis went to buy food in the villages Seth's spies found where she was hiding. Seth disguised as a snake and went into her hiding place. He found Horus alone and being a snake bit and poisoned the child. The poor mother brought the baby to the villagers and asked for their help to no avail. she cried out in despair. Nephtys, her sister, advised her to stop the Sun Boat of Ra and ask him for help. Isis, who was aware of Ra's secret name, used it to stop his boat. Ra through his messenger, Thoth assured her of the safety of Horus by promising that the Sun Boat would stop untill Horus was recovered. Ra kept his promises and Horus was cured. Horus grew to become a hero, and when he was ready, Isis gave him great Magic to use against Seth. Horus found Seth and challenged him for the throne. They fought for many days, until Seth gave up, and was castrated. Horus did not kill him, lest he be just as wicked as him. A fight broke up among the Gods who supported Horus and the Gods who supported Seth. But realizing that their quarrel would disturb Ma'at, or the balance of life,they asked the wise Neith for for his arbitration. Neith ruled that Horus was the rightful heir to the throne. Thus, Horus cast Seth into Darkness, where he lives to this day, still scheming to overthrow Horus.

|

Judgement before Osiris (detail),

This is the weighing of the heart scene. Anubis conducts the weighing on the scale of Maat, against the feather of truth. The ibis-headed Thoth, scribe of the gods, records the result. If his heart is lighter than the feather, it is the sign of his innocence and Hunefer is allowed to pass into the afterlife. If not, it is the sign of his wickedness and his heart will be eaten by the waiting chimeric devouring creature Ammit, which is composed of the deadly crocodile, lion, and hippopotamus.

|

Every king of Egypt was identified with Horus during his life and with Osiris after his death, and Egyptians performed rituals and made offerings to gain the favor of these gods who are featured prominently in their art.

Canonical Proportions in Egyptian Design

|

(From L. to R.) Hesire Seqqara of the Third Dynasty, a nobleman of the Sixth Dynasty, and Mererurka Seqqqara of the Sixth Dynasty.

Note that these three figures are depicted on a grid of 19 squares in height. The canonical ratio of 18/11 shows 18 square from the hairline and 11 square from the navel.

|

Whether carving statues or painting figures, the Egyptian graphic designers used a grid system in order to adhere to a canon of aesthetics, which determined some strict ratios. As Iversen has pointed out, the Egyptians frequently referred to their works of art as being 'true', which means they wanted to represent the natural proportions, and perhaps even the true dimensions of the objects. Grids were used to control the proportions of two-dimensional relief sculpture and to line up the sides, back, and front of sculpture. The evidence of grids is often found in unfinished relief sculpture or in paintings where a layer of paint has peeled off to reveal the traces of grids. These traces have provided the data to study how Egyptian artists worked.

Grids are first appeared in 2125–1991 BC during the Eleventh Dynasty and remained in force until the end of the 26th Dynasty in the New Kingdom. The Egyptian artists first drew horizontal and vertical grid-lines on the surface of the wall they intended to paint, or on a rock they intended to carve. The grid canonically determined the aesthetic proportions of the figures, which was 18 units to the hairline, or 19 units to the top of the head. The height of the figure was usually measured to the hairline rather than the top of the head, perhaps because the head often were concealed by a crown or head piece. Various parts of body was placed on precise segments of grid lines. For instance, the connection of the neck and shoulders was placed at the row sixteenth, the elbow at the row ninth with width of six squares. The width of female figures was only between four and five squares. The face is two squares high, the shoulders are aligned at sixteen squares from the base of the figure, the elbows align at twelve from the base, and the knees at six. The grid system thus allowed artists to create striking compositions of harmony and consistency that are scalable to colossal statues or tiny figures in hieroglyphic scripts.

Vertical Perspectives with Multiple Viewpoints

|

| Nebamun hunting in the marshes, fragment of a scene from the tomb-chapel of a wealthy Egyptian official called Nebamun, C. 1350 BC. |

|

| Nakht hunting birds in the marsh: Nakht is shown both on the left and the right (his family is also shown twice). On the left he holds a boomerang, on the right he hunts with a spear - the spear was never painted in (most probably because Nakht had died), Tomb of Nakht - Scribe of the Granaries (reign of Tuthmosis IV) |

The grammatical rules of Egyptian visual communication were framed within the two aspects of 'Frontality' and 'Axiality'. The rules of axiality meant figures were placed on an axis. Proportions of figures were related to the width of the palm of the hand so there were rules about proportions of head to body. The faces were devoid of emotional expression. Hieratic scaling dictated that the sizes of figures were determined by their importance. The proportions of children did not change; they are just depicted smaller in scale. Servants and animals were usually shown in smaller scale. In order to clearly define the social hierarchy of a situation, figures were drawn to sizes based not on their distance from the painter's point of view but on relative importance. For instance, the Pharaoh would be drawn as the largest figure in a painting no matter where he was situated, and a greater God would be drawn larger than a lesser god.

Axiality, proportion and hieratic scaling indicate that Egyptian artists would have had to use mathematics to construct their composition. Ancient Egyptian artists used vertical and horizontal reference lines in order to maintain the correct proportions in their work. The tombs walls still carry the traces of these grids used to ensure the conventions were kept to by the lower and apprentice artists working for the master artist. Political and religious, as well as artistic order was maintained in Egyptian art. Important figures were not usually depicted overlapping, but figures of servants were. Each object or element in a scene was designed and drawn from its most recognizable angle. The objects in a scene were then grouped together to create the whole. This is why images of people show their face, waist, and limbs in profile, but the eye and shoulders are shown facing frontally. These scenes are composite images designed to provide complete information about the relationship of the objects to each other, rather than from a single viewpoint.

In short, Egyptian art's perspective was complex and geared towards enhancing the harmony of a composition, while providing the most complete information. In their figurative paintings artists realizing the fact that they are representing a three dimensional geometric body in a restricted two dimensional surface, opted to add other visual dimensions to achieve their orderly aesthetics ideals while conveying a "true" message. They typically used size as one of their dimensions in order to indicates the hierarchical importance of characters. For instance, as we argued before kings are often depicted much larger than his subjects. In general, this resulted in a vertical perspective. Other dimensions were employed through multiple points of view, that would allow the human figures to be represented from the angle of view where they are best defined. Thus, heads are defined in profile with protruding nose and lips. The eyes in profile are depicted from the front view, looking at the viewers. The shoulders are seen from the front, their torsos and hips are depicted in three-quarter view point which allow the legs and arms to be seen in profile with legs extended when the figure is walking.

Distance of a figure, with respect to the viewer, is either presented by the overlapping of the bodies or by placing of the more distant figures above the ones in the foreground. However, the prominent dignitaries rarely overlap one another. Husbands and wives are depicted in a close distance from each other so that only their arms may overlap. The important peoples' bodies had to be represented complete and according to the canons. However, the lower ranking individuals, servants and slaves were often depicted as overlapping. The artists used such occasions to introduce some rhythmic repetitive patterns with these overlapping bodies so as to enhance the aesthetics of their works.

|

| Queen Nefertari bringing an offering to Goddesses Hathor and Selkis, Tomb of Queen Nefertari, wife of Rameses IInd. Thebes. |

In representing objects and landscapes the artists used the same multiple points of view technique. For instance, in the image Queen Nefertari bringing an offering to Goddesses Hathor and Selkis, we can see the goddesses are sitting in profile. The table-leg in front of them is represented from front viewpoint, the tabletop is viewed directly from above. The offerings on the tabletop are arranged vertically, so that each item can be identified by the viewer.

Egyptians paid particular attention to represent various modes of production at various stages of the of work, in farming, wine making and so on. In many of their tombs, such as tomb of nakht, various scenes of daily works such as ploughing, digging, sowing, stages of the harvest: the measuring and winnowing of the grain , the reaping and pressing of the grain into baskets and so on are depicted.

|

Various Stages in the Production of Grains. The Mortuary Chapel of Menna, superintendent of the estates of the king and of Amen, at the middle of the 18th dynasty, Thebes.

In the top row from left to right, a slave is kissing the foot of the overseer, the lands are measured by means of a rope, from which the knobs, that assured the correctness of the measurement, have been struck out by the avenger, in order that Menna may never again count his acres. In the second row, Menna's chariot and servants await to carry him to his fields, the quantity of his grain is recorded by the scribes; Menna stands under a canopy while servants bring him drink. In the third row, Menna sits under a canopy, outside of which is a tree with birds-nests built in it.

|

|

Mortuary Chapel of Menna, superintendent of the estates of the king and of Amen, at the middle of the 18th dynasty, Thebes.

In the top row from left to right, a boy walks along driving an animal, and carrying a small kid. Menna waits under a canopy to watch the arrival of a transportation boat. A servant receives the traders as they come ashore, and two sailors are punished with lashes for their wrong doings. In the second row, scenes of winnowing and threshing are illustrated.

|

|

| Sennedjem and his wife harvesting grain, from the tomb Sennedjems at Deir el Medina. |

|

| Production of wine - two laborers pick the grapes, the juices are then squeezed out of them by men on the left - while a man is filling jars from a tap |

The Egyptians believed that the pleasures of life including the times of prosperity could be made permanent by depicting scenes like; A feast for Nebamum, Nebamun hunting in the marshes, Sennedjem and his wife harvesting grain, Nakht and his wife sit before offerings, and so on. In these paintings the humanity rejoice, the family and friendship is glad, the nature and water resound; and the fields are jubilant. Overall, scenes of life, hunting and farming in the Nile marshes and the abundant wildlife supported by that environment symbolized rejuvenation and eternal life. As images like; Nakht hunting birds in the marsh, or Nebamun hunting in the marshes reveals, The geese, of several different species are depicted, and the colours are natural and subtle. Egyptian artists studied carefully the wildlife of their surroundings and paid utmost attention to detail in depicting the birds, fish, cattle, crocodiles, wildcats, butterflies and so on.

The Egyptian nobles were fond of elaborate parties and feasts as their main form of entertainment. Listening to music, watching dances, being served with foods, and friendly chats in an orderly and civilized manner were the main features of these parties. Both men and women were invited, and dining couches and small tables were provided for the guests, who regaled themselves with dishes of fowl, game, fish, bread, and wine. Women wore elegant dresses, and they paid particular attention to style and design of their dress, jewelery and furniture.

|

| Nebamun’s cattle, fragment of a scene from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, around 1350 BC |

|

| A feast for Nebamum, bottom half of a scene from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, C. 1350 BC |

|

| A feast for Nebamum, top half of a scene from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, C. 1350 BC |

|

| A feast for Nebamum, top half of a scene from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, C. 1350 BC |

|

| Senejem and His Wife, Tomb of Nakht |

|

| Nakht and his wife sit before offerings, Tomb of Nakht - Scribe of the Granaries (reign of Tuthmosis IV) |

|

| These female musicians are sensually painted in such a striking detail. The graceful nude lute-player dances to the accompaniment of a beautiful harpist and an elegant flute player. Her body is seen in front-view while her head is turned in profile to speak to her friend. |

|

| The tomb of Nakht; his wife tenderly holds a bird in her hand. |

|

| The tomb of Nakht, a nude young girl leaning to offer perfume to three female dignitaries. |

|

| Birds are being caught in nets and plucked. The filled net is a complex of wings and colors |

|

Detail from the joint Book of the dead of Herihor and Queen Nodjmet.

They both make obeisance towards offerings and a Weighting of the Heart scene, and Osiris seated beyond. Removed from the Deir el-Bahari royal cache before 1881. British Museum. |

|

| The tomb of Sebekhotep in the reign of Thutmose IV (c. 1400-1390 BC), The wall from which this fragment came almost certainly showed Sebekhotep receiving the produce of the Levant and Africa, which he then presented to the king. |

Sebekhotep's tomb is located on the West Bank at Luxor, at the north end of the hill of Sheikh Abdel Qurna, the site of the tombs of most of the high officials of the Theban region in the Eighteenth Dynasty before the reign of Amenhotep III. He was an important treasury official in the reign of Thutmose IV (c. 1400-1390 BC), bearing the title 'overseer of the seal', in effect the minister of finance.

Visual Communication on the Pazyryk Carpet (Circa 400 BC)

The Pazyryk carpet, hailed as the oldest known example of visual communication through textile art, was uncovered in 1949 within the Pazyryk Valley of Siberia, nestled in the Altai Mountains. This extraordinary artifact, excavated from the tomb of an Iranian-Scythian noble, has been dated through radiocarbon analysis to the 5th century BC.

Despite its ancient origins, the weaving technique employed in the creation of the Pazyryk carpet reveals a remarkable sophistication, suggesting a well-established tradition of carpet-making long before its time. Nearly square in shape, measuring 1.98 by 1.89 meters, the carpet's intricate design is a testament to both artistic and technical mastery.

The central field, a rich blend of dark red and gold, is framed by two distinct borders. The inner border showcases elegantly stylized depictions of deer, while the outer border presents dynamic images of knights on horseback. Within the central area, the design is dominated by minimalist rectangles adorned with X-shaped patterns, stars, and cross motifs. These repeating symbols are meticulously arranged, creating a visual rhythm that divides the space into harmonious sections. Such motifs are not isolated to this singular piece but are emblematic of a broader tradition in the creation of Oriental carpets, reappearing in numerous other examples from the same cultural sphere.

Housed today in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, the Pazyryk carpet is not only an artistic masterpiece but also a valuable cultural artifact, offering profound insights into the rich visual language of ancient societies.

Mural art of Pompeii and Herculaneum

The visual arts of ancient Rome included a long history of mural painting, and much of what we know about it comes from the excavated ruins of Pompeii and the nearby small town of Herculaneum. Interestingly, visual artists from both cities provided a wealth of information and can communicate with us about various aspects of Roman life in AD 79. Herculaneum, for example, was once a thriving city and port in the region surrounding the Bay of Naples. It was made up of amazing villas and beautiful homes for the rich and famous. Unfortunately, it is much less excavated, as it now sits beneath a bustling modern city, and its soil is so much more compacted than Pompeii due to the dense volcanic material littering the site.

Roman painting in general did not survive, but the eruption of Vesuvius near Naples in AD 79 buried the cities in volcanic ash, which served to preserve these works of art. An important eyewitness account by Pliny the Younger (A.D. 61-113) offers us a glimpse of that fateful day in A.D. 79 when the eruption of Mount Vesuvius buried an entire town and most of its inhabitants. Pliny, whose uncle died in the disaster, vividly describes sheets of fire and enormous pumice stones raining down from the volcano as well as people running desperately towards the sea, terrified for their lives. Pompeii was covered with a thick layer of pumice stone and ash up to five meters deep, while its nearest neighbor Herculaneum was buried in lava mud up to fifteen to twenty meters deep. It was not until 1748 that Pompeii and to a lesser extent Herculaneum were accidentally rediscovered.

Rather than having windows, Roman houses were built around a central courtyard, so the mural was both decorative and served to visually enlarge the interiors. They were expensive to put into service and were mostly found in the homes of the wealthy.

Dionysiac Frieze,Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii, 60-50 BC

It is thought that the figures here are performing rituals associated into the initiation into the cult of the god Dionysus (Bacchus).

Fresco of the rite of the goddess Isis, Herculaneum, Italy.

Isis was an Egyptian goddess whose worship spread all over the Mediterranean. It arrived on Pompeii’s doorstep at the end of the 2nd century B.C and archeological evidence suggests that the cult of Isis (and of Dionysus) reached its height in popularity probably in Pompeii and Herculaneum’s final years. When Pompeii’s origin Temple of Isis was destroyed in an earthquake in 62 AD, a new one was fully restored in its place, highlighting the importance the cult of Isis held over the town.

A rehearsal for a satire or Choregos and actors mosaic, National Archaeological Museum, Naples, c.62-79 CE.

The mosaic on the tablinum floor of the House of the Tragic Poet, which features a rehearsal scene for a theatrical performance, tells us how seriously the Pompeiians took their theaters. Interestingly, Pompeii had two stone theaters almost two decades before Rome had its first permanent stone theater.

Go to the next chapter: Chapter 2 - The Medium is the Message

.jpeg)

Wow... this website is absolutely amazing and a testament to the future. I can't believe that all of this beautiful information is available with an internet connection. This is gorgeous and I can't think of a better time to be alive.

ReplyDelete