|

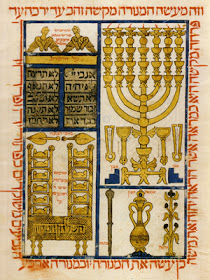

| Detail of Darmstadt Haggadah, Scribe, Israel b. Meir of Heidelberg, Germany. Courtesy of Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Darmstad (Cod. or 8, fol. 37v). |

Throughout their long history Jews had always understood the importance of visual communications in preserving their cultural identity. According to 1 Kings 6:1

Now it came about in the four hundred and eightieth year after the sons of Israel came out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon's reign over Israel, in the month of Ziv which is the second month, that he began to build the house of the LORD.The First Temple was built in the 10th century B.C. in Jerusalem and the Old Testament describes it as a magnificent piece of art in which Solomon spared no expense for its beautification. It is described as overlaid with gold and decorated with cherubim (I Kings 6). He ordered vast quantities of cedar wood from King Hiram of Tyre (I Kings 5:2025), had huge blocks of the choicest stone quarried, and commanded that the building's foundation be laid with hewn stone. To complete the massive project, he imposed forced labor on all his subjects, drafting people for work shifts that sometimes lasted a month at a time. He assumed such heavy debts in building the Temple that he is forced to pay off King Hiram by handing over twenty towns in the Galilee (I Kings 9:11).

|

| An incised depiction of the Temple Menorah, found at the site of the Temple in the Old City of Jerusalem. Israel Antiquities Authority |

In 597 BCE. King Nebuchadnezzar the Great of Babylon after plundering the gold and silver of the Jerusalem Temple and Royal Palace marched back to Babylon with several thousand Judean prisoners of war. Ten years later he would return to Jerusalem to avenge and to destroy First Temple, because Zedekiah had become king of Judah and he had not been the loyal vassal.

The original structure of the Second Temple, before it was refurbished by the Hasmoneans, and later, more extensively by king Herod, was built at the decree of Cyrus the Great, King of Iran . Indeed, vessels from the First Temple, recovered by the Persians from the Babylonians whom they had conquered, were returned to the Jews to facilitate and encourage the rebuilding of the Temple.The Talmud describes the beauty of the Herod’s Second Temple, declaring, “He who has not seen the Temple in its full construction has never seen a glorious building in his life” (Tractate Succot 51b). After the destruction of the Second Temple by Roman emperor Titus in 70 A.D—an event commemorated on the Arch of Titus in Rome and in Jewish liturgy—images of the Temple’s furnishings, especially the celebrated gold menorah, or seven-branched lamp, became emblematic of Jewish religion.

|

| Judaic Vessels |

For instance, with the discovery of the third-century archaeological site of a synagogue in the Roman garrison town of Dura-Europos, in Asia Minor we learn that a narrative form of Judaic art also existed, which depicted the figures from Bible stories as a way of sharing and teaching Torah to its prosperous community. Like its neighboring Christian meeting house and the Mithraic shrine, devoted to the Persian sun god, the Jewish narrative or ceremonial art, that was deeply rooted in its rich culture, were sumptuously adorned on the splendid murals and manuscripts with narrative scenes from their collective memories. On their synagogues painted tiles of zodiacal symbols ornamented the ceiling, and plaques with dedicatory inscriptions give some indication of the individuals and families who funded the building of such synagogues.

|

| Bowl Fragments with Menorah, Shofar, and Torah Ark |

The earliest Judaic illuminated manuscripts that are found belong to the 10th century, and were created in the Middle East . There are also later manuscripts from the early 13th century Iberia, France, Germany, and Italy. Some the colophons in certain manuscripts indicate that the illuminations and illustrations were done by renowned Jewish artists. As well, some Christian miniaturists have been commissioned to produce the art works for other manuscripts . Hence the definition of “Jewish Manuscript Art” in the Middle Ages does not necessarily implies creation by Jewish artists.

The first Hebrew illuminated manuscript to attract scholarly attention was the Sarajevo Haggadah, a Sefardi manuscript from the 1330s. It was eventually published in 1898, and from that time on scholars have utilized various methodological approaches to study and analyze medieval Jewish book art. In 1950s Kurt Weitzmann’s recension theory replaced the bibliographical approach of the earlier decades. Weitzmann theorized that every narrative image cycle was necessarily emulated from an early predecessor, and that it is the aim of the art historian to reconstruct a prototypical version. According to this theory the earliest surviving example of a Hebrew illuminated manuscript is a Pentateuch fragment from Egypt, dated 929, and several Middle Eastern Bibles and other texts were produced during the subsequent centuries. The decoration of these books was rooted in the tradition of Middle Eastern manuscript illumination and did not include any figurative art.

|

| Detail of the 'Maror' page of the Sarajevo Haggadah (courtesy of the Foundation for Jewish Culture) |

The reality of the Jewish community under Islamic rule, during the Middle Ages and during the Renaissance, explains much of the evidence of restrictions in Jewish art which focused on the construction of synagogues and the illustration of manuscripts, in those eras. Countries with strong Muslim influences, including Spain, featured much less physical representation of human forms in art than the Northern European communities, because Muslims shun such literal renderings of human forms.

|

| "Moses Receives the Ten Commandments." Machsor mechol hashana. Germany, ca. 1290, leaves 59b, 50a. Vellum (2) |

|

| The Rothschild family commissioned this Persian-style Haggadah from Victor Bouton in the second half of the 19th century. The Braginsky Collection (Ardon Bar-Hama) |

A similar tradition of aniconic book decoration appeared later in post-reconquest Iberia. In parallel, beginning in the 1230s, a rich figurative and narrative art began to develop in Christian Europe, including Bibles, prayer books, haggadot (the liturgical text for the Passover ceremony), compilations of the ritual law, and miscellanies. Hardly any Hebrew illuminated manuscripts from the Byzantine world have survived, the only extant works being a few haggadot from the 16th century, which have not yet been studied in any depth. It should however be noted that unlike Christian Hellenist and Latin communities the Jewish culture was quite familiar with their own Biblical stories that made it unnecessary for visual communication of those narratives to the illiterate pagan masses. As the Encyclopedia Judaica states, “For the Jews, with their high degree of literacy due to their almost universal system of education and their familiarity with the scripture story, this was superfluous.”

By the 20th century, Jewish artists of the Diaspora while moving away from Judaism were among the vanguard of the modern artistic liberation. Artists like Camille Pissarro, Marc Chagall, Amedeo Modigliani, Chaim Soutine, Jacques Lipchitz, Moïse Kisling, Ossip Zadkine, Joseph Csáky , Jacques Chapiro, El Lissitzky, were able to incorporate their Jewish cultural heritage into the grammar of their modernist art. In their book Peintres juifs à Paris-- (Paris: Denoel, 2000) the authors; Nadine Nieszawer, Marie Boye, and Paul Fogel, estimate that over five hundred Jewish artists were working in Paris in the interwar era. Many of these artist were part of the École de Paris movement, who arrived in Paris in the decade before the First World War.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License.

No comments:

Post a Comment