|

| Leszek Zebrowski, Carmen - Bizet, 2009 |

The Polish opera, film, and circus posters occupy a prominent place in the history of graphic design. Firmly grounded in the vast, rich and sophisticated heritage of Poland's visual communications since the early 20th century, they are informed by the tragic history of the Polish life under long centuries of captivity. The Polish heritage have inspired the creation of a symbolic language for transmission of various layers of socio-cultural meanings which are at the core of its culture and forms the Polish School of Opera, Film, and Circus Posters. A school that is distinguished by its thought provoking and bold compositions, masterful craftsmanship, and a unique aesthetic design that amalgamates some of the Polish cultural identity in the framework of various styles such as Jugendstil, Secessionism, Japanism, Surrealism, Cubism and other modernist elements of Pop art and Street Art. Above all, the Polish visual communication posters are characterized by their artistic integration of image and text that set them apart from the usual western design of advertising. To comprehend the intricacies of the artistic vision of the Polish Schoolone has to approach it from a historical perspective.

The Polish history starts at the 11th century, when various principalities became united for the first time under a Polish banner. But the first reunification was short-lived. Nevertheless, two centuries after its second reunification, in the 14th century, Poland reached the zenith of its power, when its territories stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Yet, it suffered in the tumultuous years of the 17th century with the invasion of the Swedes, breaking up of hostilities with the Turks, and a Cossack rebellion in its southeastern territories. An exhausted Poland was divided up by the three autocratic monarchies of Russia, Austria and Prussia at the end of the 18th century. During more than a century of occupation successive generations of Poles struggled for their independence. The motto of "For your freedom and ours" -- Za naszą i waszą wolność, was the battle cry of the exiled Polish soldiers from their occupied country, fighting in various struggles all over Europe against tyrants, which became the symbol of Polish struggle for a democratized Europe.

Poland gained back her freedom at the turn of the 19th century, when France under Napoleon became her ally and defeated the three occupying powers. Under the Treaty of Tilsit the Duchy of Warsaw was established on the Prussian occupied Poland. A Polish government was formed, the Napoleonic Code was introduced and peasants were given personal freedoms. However, with the defeat of Napoleon at Leipzig in 1813, after his disastrous expedition to Russia, the Congress of Vienna returned part of the Duchy, together with Poznan, to Prussia. The remaining lands were turned into the Kingdom of Poland, but it became a protectorate of Tsar Alexander I of Russia. Many Poles joined underground movements and planed for an uprising. The first uprising broke out in Warsaw on November 29, 1830. An independent government was established , with the Sejm dethroning the Tsar. But, the Poles were defeated in the Polish-Russian war that followed, and Russia regained its control.

The post-uprising period saw an intensification of Russification pressures in the Russian occupied Poland, and Germanization in the Prussian part. Those pressures resulted in a growth of national awareness. The Polish culture responded in the context of its 19th century Romanticism and Positivism. Jan Matejko (1838-1893), the most popular creator of romantic visions of Polish history, declared, "Art is a weapon of sorts; one ought not to separate art from the love of one's homeland." Romantic literature promoted the image of a heroic freedom fighter, who by sheer strength of his spirit engages in a lonely battle the evil forces of violence : "Reach where your vision does not reach, break up what mind cannot break," was the call of romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz. The other literary giant of the time, Juliusz Slowacki, described heroes as "like stones thrown by God on a rampart." In music Frederic Chopin used Polish folk and national motifs. This romantic image of Poles as a chosen people with a messianic mission was challenged by Positivist of Cracow who were loyal to the Austrian Empire, and were reacting to the disastrous aftermath of the January Uprising of 1863 against Russia.

|

| Polonia by Stanislaw Wyspianski, 1893-94, Pastel, National Museum, Cracow |

After decades of forcible Germanization, Vienna offered some limited measure of political, cultural and economic autonomy to Galicia, the Polish area under the Austrian occupation. In 1869 Cracow gained some limited degrees of self rule and, the right to use the Polish language in schools and in the courts. Four years later with the establishment of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences, the city turned into a Polish center for academic research, particularly in the humanities. In 1898, Jan Wdowiszewski,organized the first International Exposition of the Poster in Krakow. Wdowiszewski who for thirteen years, from 1891, was the managing director of the Technical Industrial Museum of Krakow, in his introduction to the exhibition argued that the power of posters stems from the fact that, like a mirror, they reflect both the physical image as well as the ideological thinking of a society. Two years later the Polish Science and Literature Association -- Związku Naukowo-Literackiego in Łódź published William Morris's Art and the Beauty of the Earth, in which Morris argued that if one desires to live with art then

it must be part of your daily lives, and the daily life of every man. It will be with us wherever we go, in the ancient city full of traditions of past time, in the newly-cleared farm in America or the colonies, where no man has dwelt for traditions to gather round him; in the quiet countryside as in the busy town, no place shall be without it. You will have it with you in your sorrow as in your joy, in your work-a-day hours as in your leisure. It shall be no respecter of persons, but be shared by gentle and simple, learned and unlearned, and be as a language that all can understand. It will not hinder any work that is necessary to the life of man at the best, but it will destroy all degrading toil, all enervating luxury, all foppish frivolity. It will be the deadly foe of ignorance, dishonesty, and tyranny, and will foster good-will, fair dealing, and confidence between man and man. It will teach you to respect the highest intellect with a manly reverence, but not to despise any man who does not pretend to be what he is not; and that which will be the instrument that it shall work with and the food that shall nourish it shall be man's pleasure in his daily labour, the kindest and best gift that the world has ever had.

And, these words appear to have resonated with the polish soul.

|

| Stanislaw Wyspianski (1869 - 1907), Caritas (Love), 1904 |

|

| Jozef Mehoffer – 1923 |

|

| Karol Frycz, "Helena Sulima as Rachel in Stanislaw Wyspianski's Drama Wesele (the Wedding), from the Melpomene's Portfolio" , colour lithograph, 1904, National Museum, Cracow |

|

| Kazimierz Sichulski – Contemporary Polish Exhibition of Architecture, Sculpture and Painting , 1910 |

|

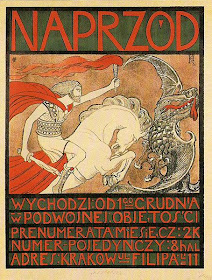

| Henryk Kunzek – Forward , 1910 |

After the onset of the WWI, Germany and the dual empire of Austria-Hungary occupied the entire Polish territory, in 1915. The victors permitted the organization of local self-governments and city councils, as well as the Polonization of education and the setting up of a university and a polytechnic. However, the Polish economy was in ruin, and what remained of industry and farming was ruthlessly plundered by the occupiers. Nevertheless, Poland was lucky that by the end of the WWI, all of its three occupiers were weakened drastically. Austria-Hungary, and Germany were defeated, and the Bolshevik Russia was being isolated and was not a member of the victorious side. As a result, a free Polish Republic was established by France, Britain and the US in the congress of Versailles.

The twenty years of independence, until the onset of WWII, was a period of Polish growth and prosperity. The Polish Airlines, LOT, was established on January 1st, 1929. Advertising posters were used as an effective tool, to shape the company's image at home and abroad. LOT worked with leading Polish graphic artists to build confidence in its flight and to reduce any flight anxiety. In 1924, Józef Mehoffer, one of the most renowned representatives of Art Nouveau school, created a poster advertising Polish Airline Aero Lloyd that flew from Gdańsk, Lvov and Warsaw. Five years later, a poster by Tadeusz Gronowski (1894-1990) encouraged the public to “carry passengers, mail and cargo” by LOT Airlines. An elegant silhouette of Fokker is accompanied by three storks, as a symbol of safe flight under the blue skies.

Tadeusz Gronowski (1894-1990) became the first Polish artist dedicated solely to posters. Gronowski maintained that a graphic designer must not impose his taste on the viewer since the poster is a "communication between seller and public". His 1926 poster for Radion soap exemplifies this attitude. The simple geometric image of a black cat going into the wash basin and coming out white personified "Radion does the cleaning for you!" .

|

| Tadeusz Gronowski, Tier, 1923 |

|

| Tadeusz Gronowski ,7th International Eastern Fair, Warsaw 1927 |

|

| Tadeusz Gronowski, Advertisement Radion soap, 1927 |

|

| Tadeusz Gronowski, LOT the Polish Airlines, 1939 |

A nother artist Stefan Norblin (1892, -1952), known primarily for his modernist and Art Nouveau style was commissioned for a series of tourism promotional posters.Born in Warsaw into a family of artists. Stefan Norblin's great-grandfather was known painter Peter Norblin. Stefan studied painting in Antwerp and Dresden. In 1920 he took part in the Polish-Soviet war. After the war he returned to Warsaw, where he married Lena Żelichowska, then well-known actress and dancer. He left Poland in 1939. During the Second World War he was in India, where he created a series of paintings for the Maharajah of Jodhpur while decorating the interior of the Umaid Bhawan Palace, the largest private residence in the country. After the war he settled in the United States, where he earned his living as a portraitist. He died in San Francisco in 1952.

|

| Stefana Norblina, Polska Zakopane, 1925 |

|

| Stefana Norblina,Gdynia, 1925 |

|

| Stefana Norblina, Polska, 1925 |

|

| Stefana Norblina, Warszawa, 1928 |

|

| Stefana Norblina, Wilno, 1928 |

|

Stefana Norblina, Lwow, 1928

|

T

adeusz Trepkowski a renowned graphic designer pushed the minimalism approach to a new horizon and created some of the most effective visual communication posters, such as his 1937 Reka skaleczona nie moza pracowac -- The hand crippled, Meuse not work, in which the three rhythmic hammer holding hands with a fourth of injured one convey the message of the importance of safety. Except for a few month study at the Municipal School of Decorative Arts, he was basically a self-taught artist. When he was a teenager of just sixteen years old he undertook his first project. He won a number of prizes for his posters in various competitions including for PKO in1933 , and for the Tychy brewery in 1935 and the Grand Prix at the International Exhibition in Paris for his poster, Caution,in 1937. His posters were of political, social, health and safety nature. He also created some film posters.

In the final years of his life he was criticized for its departure from the rules of socialist realism. He died suddenly of a heart attack , when he was just forty years old .

|

Tadeusz Trepkowski, The hand crippled, Meuse not work, 1937

|

|

Maciej Nowicki &Stanislawa Sandecka, Everyone Fight Against Tuberculosis, 1934

|

|

| Maciej Nowicki & Stanislawa Sandecka, 2nd Meeting of Polish Youth from Abroad, 1935 |

|

Jerzy Hryniewiecki & Andrzej Stypinski, Eastern Trade Fair, 1930

|

|

| Ball of Young Architecture |

|

| 10 Years of PZP, 1934 |

Russia and Germany could not accept the outcome of Versailles treaty with respect to Poland, but to buy time they both concluded non-aggression pacts with Poland -- Russia in 1932 and Germany in 1934. At the beginning of 1939, the Nazi Germany were ready to attack Poland, and in response Britain guaranteed the independence of Poland, which was later affirmed by France. The German onslaught on Poland on September 1, 1939, started the WWII. On September 3, Britain and France declared war on Germany, and on September 17, the Soviet Russia invaded Poland. Confronted with the enormous military might of the enemies and receiving no assistance from France and Britain, Poland was forced to submit.

|

| Hubert Hilscher, Francesca da Rimini, Opera of Peter Tchaikovsky, 1968 Henryk Tomaszewsk, Zemsta nietoperza - Johann Strauss, 1970 |

|

| Maciej Urbaniec, Boris Godunov, opera of Modest Musorgsky, 1972 |

|

| S. Bakowski, La Gioconda of Amilcare Ponchielli, 1973 |

|

| Stasys Eidrigevicius, Neocantes - capilla barroca, 1989 |

|

| Jan Lenica, Norma of Vincenzo Bellini, 1992 |

|

| Rafal Olbinski, La Traviata - Giuseppe Verdi, 1992 |

|

| Ryszard Kaja, Orfeusz w piekle / Orpheus in the Underworld Operetta of Jacques Offenbach, 1995 |

|

| Ryszard Kaja, Tosca - Giacomo Puccini, 2005 |

|

| Adam Pekalski, Chorus Festival, 2005 |

|

| Mieczyslaw Gorowski, Charles Gounod - Faust, 2006 |

|

| Andrzej Pagowski, Boris Godunov, opera of Modest Musorgsky, 2007 |

After the German defeat at the end of WWII the advancing Soviet troops occupied the rest of the Poland territory. Military cooperation with local Home Army units lasted until the Germans were defeated. Upon victory, Polish units were taken prisoners, and transported to the Gulag camps and Siberia. Poland's destiny was sealed at the Yalta Conference, in 1945, when its was relegated to the Soviet Russia's sphere of influence. By 1948 communists destroyed the private sector, and the market disciplines, and introduced a centrally controlled plan economy. The inevitability of change in the nature of Polish culture was evident. Heated arguments among the artists that longed for the twenty years of freedom during the inter-war period gradually silenced over the 1946- 48, and the communists exerted full control over all spheres of culture and social activities. In fact, the artists in Soviet Russia, since 1934, were instructed that their work should reflect the principle of Socialist Realism. "truthful and historically correct portrayal of reality in its revolutionary development". As far as 1973, Butkovich urged artists in an article in the Soviet Culture that they should "express the principal ideas of the time ,,, that is to follow the way of Soviet realists".

|

| Tadeusz Trepkowski, Grunwald 1410 – Berlin 1945, 1945 |

|

| Jan Lenica, Cul de Sac, 1966 |

By the Mid-Fifities, the fierce Stalinist approach was somewhat relaxed, and some artistic expression were tolerated. The Polish film industry was able to prosper. And the graphic designers used their ingenuity to express their artistic visions in dimensions that were beyond the reach of the culture-police. Furthermore, Polish film producers were able to establish relationships with the western producers, especially in France and Italy. As the Polish film establishment was not concerned about commercial aspects of the studio demand the poster became artist-driven. Posters became part of fine art, and instead of being led by the lowest common denominator in public taste, artists shaped the society's taste. In words of one commentator; "The artists requested and received complete artistic freedom and created powerful imagery inspired by the movies without actually showing them: no star headshots, no movie stills, no necessary direct connection to the title".Unburdened by the western commercial and legal restrictions Polish graphic designers used film poster venue to flourish their artistic creativity and continued working in the beaux-arts tradition of pictorial and artistic lithography.

Flisak graduated from Jose Marti High School in Warsaw, and studied architecture at the Warsaw University of Technology. He made his debut in 1950, still as a student, in the competition organized by the weekly magazine Szpilki, where later he became its graphic editor. Flisak's designs were published in Świerszczyk, Płomyczek, Polityka, weekly magazine Świat, Przeglądz Kulturalny. He also designed many movie posters. Flisak's Posters' style is often described as clumsy, deliberately ugly, non-aesthetic, and done almost casually.

|

| Jerzy Flisak, “Pane, amore e..”, Italy 1955. Directed by Dino Risi, 1958 |

|

| Jerzy Flisak, “Roman Holiday”, US 1953. Directed by William Wyler, 1959 |

|

| Rancho Texas, by Jerzy Flisak |

|

| Jerzy Flisak, “The Hitman”, Italy 1960. Directed by Damiano Damiani, 1962 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A graduate of Academy of Fine Arts in Cracow, 1952, Gorka worked for Poland's largest publishing houses and film distributors: RSW "Prasa", "WAG", "CWF" since 1950s. He was a visiting professor at a number of artistic academies in Mexico.

Lenica studied in the Faculty of Architecture at the Poznan Technical University. He was specialized in poster, graphic design, book illustration, stage design and animation. He authored numerous articles and books on poster art, and coined the term "Polish School of Poster". He lectured on poster art at Harvard University in 1974 and in Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin 1986-1994.

Mlodozeniec was born in Warsaw, the son of an experimental futurist poet, Stanislaw Mlodozeniec. He studied from 1948 to 1955 at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts at Department of Graphic Arts and Posters of Henryk Tomaszewski. He designed over 400 posters.

Eryk Lipiński was born in Kraków. He started as a caricaturist at Pobudka magazine in 1928 before enrolling at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts in 1933 graduating in 1939. In 1935, together with Zbigniew Mitzner, he founded a Polish satirical newspaper Szpilki acting as its chief editor for several years. Lipiński contributed to many other periodicals and newspapers as a caricaturist and essayist. During World War II he was one of the artists working with the Polish resistance, and was imprisoned by the Nazis in various prisons including Pawiak, Mokotów, and Auschwitz concentration camp. Lipiński joined the Polish United Workers' Party, after the war, contributing to many newspapers and magazines. In 1966 he organized the First International Poster Biennale in Poland. In 1978 he founded the Museum of Caricature in Warsaw and was its first director (it would be named after him in 2002). In 1987 he founded the Association of Polish Cartoonists (Stowarzyszenie Polskich Artystów Karykatury, SPAK).

Marek Mosinski was born in Warsaw and died in Katowice. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow and graduated with honours in 1962 in the studio of B. Gorecki. Author of more than 300 posters, he is one of the prominent representatives of the Polish poster school. His works was exhibited in 10 one-man exhibitions and about 200 collective exhibitions at home and abroad. He was awarded the Gold Cross of Merit, and was a member of the Association of Polish Artists and Graphic Designers.

|

|

| Waldemar Swierzy, Sunset Boulevard , US 1950. Directed by Billy Wilder, 1957 |

|

| Maciej Hibner, Pickpocket, France 1959. Directed by Robert Bresson, 1962 |

|

| Michal Ksiazek, Breakfast at Tiffany's , USA, 1961, director Blake Edwards, 2006 |

|

| Michal Ksiazek, Leon; the Professional, USA, director Luc Besson, 2010 |

|

| Henryk Tomaszewski, Film Poster, Ditta, 1952 |

|

| Henryk Tomaszewski, Jazz Jamboree 71, 1971 |

In words of Tomaszewski, "Politics is like the weather, you have to live with it." Tomaszewski was born in 1914 in Warsaw into a family of musicians. who expected him to devote his life to music, but in 1934, he enrolled in the Warsaw Academy of Art to study painting student. After graduating in 1939, he became interested in the work of the exiled German satirists Georg Grosz and John Heartfield, and began to draw satiric cartoons and caricatures for the Polish humor magazine Szpilki. During the Nazi occupation he continued to paint, draw, and make woodcuts, all of which were destroyed during the Warsaw Uprising. After the defeat of Nazis, he and other graphic designers like Tadeusz Trepkowski and Tadeusz Gronowski, was hired to produce posters for the state-run film distribution agency, Central Wynajmu Filmow.

|

| Henryk Tomaszewski, Film Poster, Obywatel Kane (Citizen Kane), 1948. |

|

| Henryk Tomaszewski, Inspector, 1953 |

In his posters, Tomaszewski tried to capture the mood of the films by using photographic montage, exaggerated perspectives and innovative cropping, in the context of a minimalist compositional approach, using bold colors and abstract shapes. Instead of standard typeset typefacese, he used abstract collage with expressive lettering for his Polish Cyrk (circus) posters, which became a distinct feature of his style. His art benefited from this resistance, since he was forced to come up with concealed satiric images in his work. He stayed clear of overtly political issues and focused entirely on designing posters for cultural institutions and events. During the1952 -1985 period, Tomaszewski taught at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, where he was a co-director, along with Josef Mroszczak. In 1996, he was paralyzed due to a nerve degeneration. He died in 2005.

|

| Henryk Tomaszewski, Circus, 1965 |

Maciej Ździeblan-Urbaniec was born near Zamość in 1925. He used "Urbaniec" as his nom de guerre during the Warsaw Uprising in 1944, and kept it throughout his life. In 1952 he enrolled in a two years program at the National Academy of Plastic Arts in Wrocław, and after completing the program in 1954 he entered the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw studying in Henryk Tomaszewski’s Poster Studio. He graduated graduated with honours in 1958. He became Assistant Professor in the Graphic Design Studio at the Department of Painting, Graphics and Sculpture in the National Academy of Plastic Arts in Wrocław in 1970 and five years later assumed the directorship of Graphic Design Studio of Warsaw’s ASP (Academy of Fine Arts), where he was appreciated and liked by students.

|

| Urbaniec, Leader Of Working Classes Lenin |

|

| Don't Make Noise Without Reason |

|

| Come and see Polish mountains, Poster for Tourism, 1967 |

|

| Auschwitz 1945-1965 |

|

| Work Without Such Wastes |

|

| ABC, abc |

|

| Card-Index. Rózewicz |

|

| Special SARP Congress, 1977 |

Urbaniec also worked as a graphic designer, on posters for Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy (the State Publishing Institute) for which he created book jackets and posters; including a well-known popular science book series – "plus-minus nieskończoność” or “plus-minus infinity". He won a number of awards for Best Published Novel of the Year in a competition organized by the State Association of Book Publishers in Poland, a medal in International Editorial Art Exhibition (IBA) in Leipzig and at the International Biennale of Graphic Art in Bern. He was a member of Alliance Graphique International, and participated in many poster exhibitions in Poland and around the world. In the 1970’s Urbaniec developed his unique and original style in the form of simple and powerful messages; often with the use of ingenious and humorous photographic props, rich symbolism, iconography, and exceptionally sophisticated metaphors, such as his last poster, created shortly before his death in 2004, Historia malowana na niebie or History painted in the sky.

|

| Circus |

|

| Circus |

|

| Circus |

|

| Circus |

Stasys Eidrigevičius was born in Mediniškiai Lithuania. He graduated from the College of Fine Arts and Crafts in Kaunas in 1968. In 1973, he obtained a diploma from Vilnius Academy of Fine Arts. Since 1980 he has lived in Poland. Eidrigevičius is active in many artistic fields, such as: oil painting, book-plate, book illustration, studio graphics, and photography. He has been interested in posters since 1984.

|

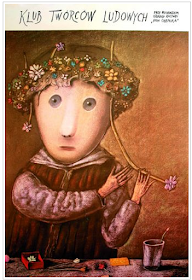

| klub tworcow ludowych, by Stasys Eidrigevicius |

|

| XIXe Rencontres internationales de marionnettiste de Pulawy, ville située au sud-est de Warszawa,by Stasys Eidrigevicius |

|

| Le thème espagnol dans l'affiche polonaise. by Stasys Eidrigevicius |

|

| Le grand théâtre du monde de Pedro Calderon de la Barca, au théâtre Lalek de Wroclaw. by Stasys Eidrigevicius |

|

| Théâtre, monde du théâtre, by Romuald Sakowicz |

Wiktor Sadowski was Born in Olendry. In 1981 he graduated from Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts with a diploma under the supervision of prof. Tomaszewski). Sadowski specializes in posters and book illustration.

|

|

| Le coq d'or opéra de Nikolai Rimski-Korsakov., by Wiktor Sadowski |

|

| La route des Indes, Wiktor Sadowski |

|

| Zupełnie nieoczekiwanie, by Wiktor Sadowski |

|

| Le maître et Marguerite by Mikhaïl Boulgakov,Wiktor Sadowski |

Starowieyski studied painting at the Cracow Academy of Fine Arts under Wojciech Weiss and Adam Marczynski (1949-52) Studied Painting at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts under Michal Bylina, and graduated in 1955. For a number of years he divided his time between Warsaw and Paris, intensively making some 300+ posters, quickly becoming one of the finest representatives of the first Polish school of posters. His posters are often full of drama, tension, exuberance, grandeur, and ornament. At once both grotesque and beautiful, his baroque style and macabre attention to anatomy often begets the surreal and fantastic. His penchant for 17th century draftsmanship is apparent in his masterful use of chiaroscuro and calligraphy. He often worked ambidextrously. He was the first Pole to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (1985).

|

| Franciszek Starowieyski, Upior z Morrisville (The Phantom of Morrisville) Poster for the Czech comedy film directed by Borivoj Zeman, 1967 |

|

| Franciszek Starowieyski, Tragiczne polowanie, film poster, Poland, 1967 |

|

| Franciszek Starowieyski, Teresa Desqueyroux, film poster, Poland, 1964 |

|

| Billet de retour, 1978 Franciszek Starowieyski |

|

| Adalen 31, Franciszek Starowieyski |

|

| Ali Baba et les 40 voleurs, by Witold Chmielewski |

CYRK posters, created over the 1945- 1989 0eriod are the quintessential posters of the golden age of the Polish School of Posters. During this time, the Polish Government financially supported and encouraged poster art. In 1962,the state circus agency, the United Entertainment Enterprises (ZPR), commissioned leading artists to develop a modern approach to the circus poster. The aim was a revised look for the circus poster to parallel the circus’ efforts to upgrade its image. These new CYRK posters were of contemporary artistic look with a minimum concern for advertisements in terms of concrete pitch for sale; but rather, an aesthetically pleasing visual communication device that informed the public that an exciting and modern circus was coming to town. Based usually on a single theme of common symbols––jugglers, clowns, and animals–their metaphors and allusions created a wonderful artistic expression that should not only be viewed, but should also be read, pondered, and digested.

|

| Antoni Cetnarowski, Upside down cyclist, 1970 |

|

Jan Gruszczynski, bathers on unicycle, 1970 |

| |||

| Jacek Neugebauer, Tightrope walker, 1970 |

|

| Hubert Hilscher - Circus, 1979 |

|

| Anna Kozniewska, Gal roller skating, 1971 |

|

| Jan Sawka, Acrobatic Pyramid, 1975 |

In 2003, Joanna Gorska and Jerzy Skakun have established Homework, a Warsaw-based studio that has been creating posters for cultural events. Their work is inspired by the simple visual puns of Mieczysław Wasilewski and the playful illustrative style of Witkor Gorka. The artists attempt to create a distinctive style. According to Ellen Lupton they are “bringing the medium [of the Polish poster] back to life, and updating it for the twenty-first century”, Joanna and Jerzy just want their posters “to set themselves apart from the masses, simply through their quality”.

Go to the next chapter; Chapter 38 - Saul Bass, and the Art of Film Title Sequence & Film Poster

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License.

No comments:

Post a Comment