Posters from the Spanish Civil War represent one of the most painful documents of this historical period. As many eyewitness accounts show, posters were an essential part of the visual landscape in which people experiencing the tragedy of war carried out their daily tasks of survival.

The British writer Christopher Caudwell wrote home from Barcelona in December of 1936:

"On almost every building there are party posters: posters against Fascism, posters about the defense of Madrid, posters appealing for recruits to the militia...and even posters for the emancipation of women and against venereal disease."

Robert Merriman, an American volunteer fighting in Spain wrote from the same city in January of 1937:

"Streets aflame with posters of all parties for all causes, some of them put out by combinations of parties."

In Republican territory, when a house was destroyed by the enemy bombs, propaganda agencies would fix posters on the ruins in order to denounce the enemy, hoping to turn aggression into rage. In Madrid, the capital of the Republic, shop owners were exhorted to fill their store fronts with posters: "Every space must be used to incite the spirit in its fight against the enemy," stated an article in the newspaper ABC on October 30, 1936.

In Seville, portraits of two of the leaders of the military rebellion that originated the war, Generals Queipo de Llano and Franco, were posted everywhere shortly after the city was taken. Further from the front, a different lifestyle was accompanied by the same backdrop of war posters. Arturo Barea, a patent officer who is the author of one of the most sensitive memoirs of the war, wrote about his experience in Valencia, where he had arrived from the front in Madrid:

"I walked slowly through an outlandish world where the war existed only in the huge anti-fascist posters and in the uniforms of lounging militia men...a wealth of loose cash was spent in hectic gaiety. Legions of people had turned rich overnight, against the background of the giant posters which were calling for sacrifices in the name of Madrid."

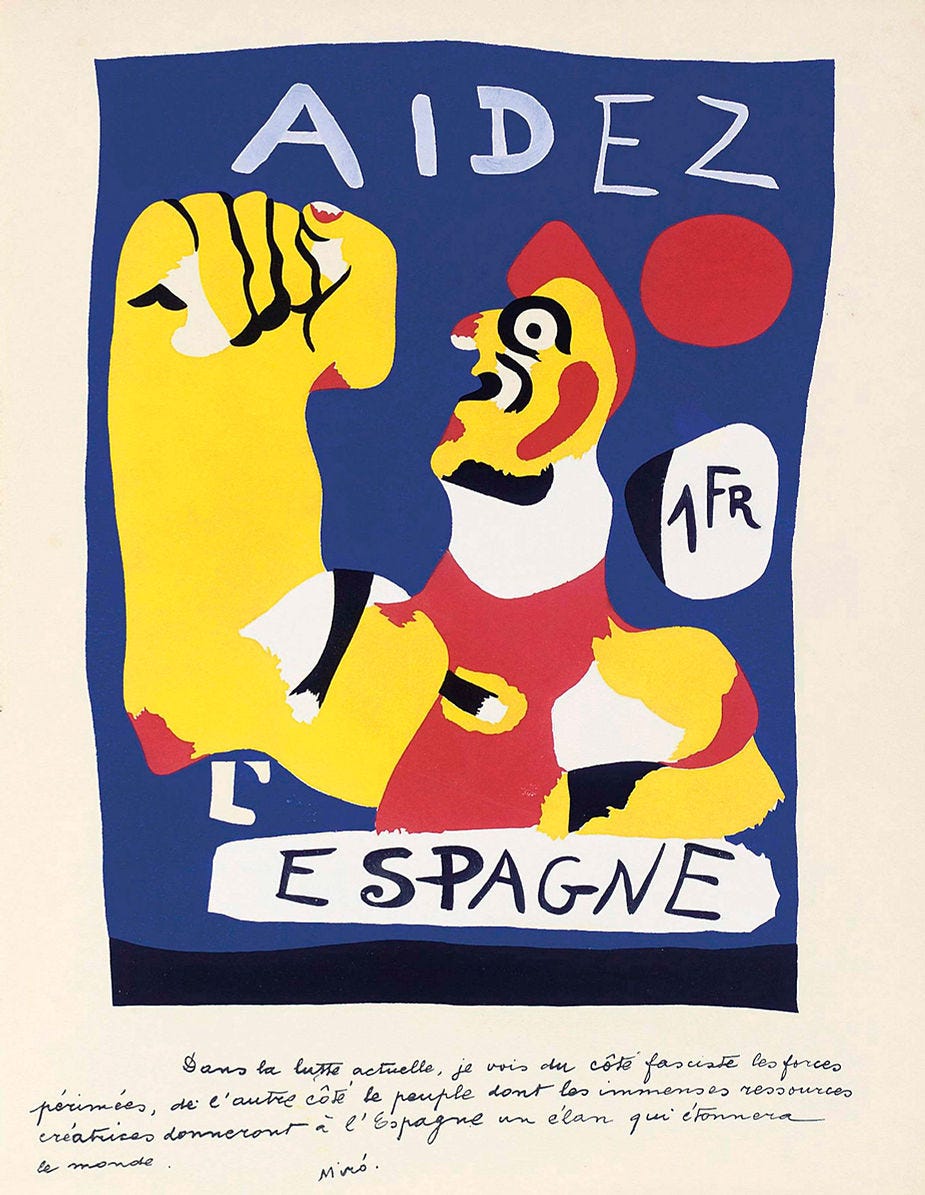

Aidez Espagne (Help Spain) Joan Miró, 1937

Miro in this poster, appeals to the international community to intervene and help the Spanish people. It reflects the themes and values of Modernism, such as experimentation, fragmentation, and disillusionment.

It was created in 1937 to raise money and support for the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War. The poster shows a Catalan peasant raising a clenched fist, a symbol of resistance and solidarity, against a bright yellow background.

The poster also features the colors of the Catalan flag, red and yellow, and the slogan “Help Spain” in four languages: French, English, Catalan, and Basque.

Miro was a Catalan artist who opposed Franco’s fascist regime and sympathized with the Republican side. He moved to Paris in 1936 to escape the violence and turmoil in Spain. He was influenced by Surrealism and developed his own style of abstract and symbolic imagery. His poster was one of the many artistic responses to the Spanish Civil War, along with Picasso’s Guernica and Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia.

By Oliver

Josep Renau:

Born in Valencia in 1907, Josep Renau was one of the artists most heavily involved in the Civil War. He was the director of the Republican government’s propaganda department and a member of the Communist Party. He created posters that used photomontage, surrealism, and social realism to promote the Republican cause and denounce fascism. He also designed the famous mural “The Spanish People Have a Path That Leads to a Star” for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris World Fair.

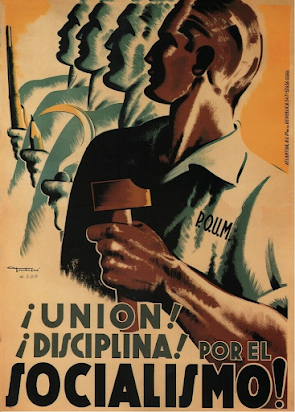

Antoni Clavé:

Antoni Clavé was born in Barcelona on 5 April 1913. He was a Catalan painter and sculptor who joined the Republican army as a volunteer. He created posters that used abstract and geometric forms, bright colors, and symbolic elements to convey messages of hope, resistance, and solidarity. He also collaborated with Pablo Picasso on the stage design for the ballet “Romeo and Juliet”. During the Spanish Civil War Clavé served as a draughtsman for the Republican government but at the end of the war he fled to France. After internment at Les Haras camp in Perpignan, Clavé settled in Paris in 1939, drawing comics and working as an illustrator. During the 1940s Clavé's painting showed the stylistic influence of Bonnard, Vuillard, Rouault and especially Picasso, with whom he became acquainted in 1944.

Carles Fontserè:

He was a Catalan painter and illustrator who was influenced by Miró and Picasso. Influenced by the art of the Mexican and Russian revolutions, Fontserè led a life that reads like a picaresque novel. Self-taught, he started work at the age of 15 in a theatre design workshop, developing his skills with cinema posters, book covers and adverts. When the civil war broke out in 1936, he became active in the union of graphic artists. He created posters that used expressionist and cubist techniques, dynamic compositions, and vivid contrasts to depict the heroism and suffering of the Republican fighters and civilians. He also designed the poster for the film “Land Without Bread” by Luis Buñuel.

Helios Gómez:

Spanish-born Roma artist Helios Gómez (1905–1956) was a gypsy painter and activist who was a member of the anarcho-syndicalist trade union CNT.

He was among the most prolific of the left wing anti-fascist political graphic artists from the country’s Republican period, before Franco’s Falange Party Fascists overtook the nation. Gómez was first published in the anarchist newspaper Páginas Libres, and he also illustrated books by Seville’s political authors. In 1927, political disputes forced his exile to Paris. According to the French writer, poet and museum director Jean Cassou, Gómez “was an artist because he was a revolutionary and a revolutionary because he was an artist.”

He created posters that used woodcut, collage, and stencil methods, dark tones, and dramatic images to portray the brutality of war and the oppression of the working class. He also participated in the defense of Barcelona against the Nationalist troops.

Spanish civil wars and modernist movement in art

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the radical modernist movement emerged in art, literature and culture, aiming to challenge the traditions of the past. The Modernists were avant-garde artists, writers, musicians and architects who challenged the status-quo and sought to understand and analyse the human condition through their own unique interpretive style.

Inspired by the industrial revolution, urbanization, social changes and the tragic consequences of multiple wars, modernists experimented with new forms of expression, new materials and techniques to reflect modern life from a new perspective.

The Second Republic of Spain, that had came to power in 1931, was made up primarily of leftists and centrists. The king Alfonso XIII, a constitutional monarch, was forced to abdicate. Those victorious at the election then declared Spain a republic and monarchy was abolished. They enacted reforms to breakup the feudal system, and attempted to reduce the size of the military. As well, the republicans introduced a number of acts against the catholic church. State stopped paying priests' salaries, demanding that they should be paid by Roman Catholic Church’s funds. These reforms angered many privileged groups including the military, industrialists, land owners and the Roman Catholic clergy. They were supported by right wing countries in Europe that were fearful of Stalin’s Russia, in particular Italian fascists under Mussolini, and Nazi Germany after Hitler came to power in January 1933. The 1930’s Depression, weakened the government position further. Two powerful left wing political parties, the anarchists and syndicalists (powerful trade union groups), criticized Azana’s government for not paying attention to the plight of the unemployed workers and poor farmers who were devastated by the impact of the depression, and the extreme left organised strikes and riots in an effort to destabilize his government. Azana resigned as prime minister and elections were called for November 1933, in which the Nationalist won a majority of seats. The new government immediately nullified all the reforms.

A period of instability, strikes and riots ensued, and as result a general election was called for February 1936, in which Azana's Popular Front won and once again he became prime minister. However, the ongoing instability intensified. Franco's coup against Azana made some headway in parts of the country but in Catalonia, and especially Barcelona, the CNT (Anarcho-Syndicalist union) resisted fiercely. They declared a general strike and took to the streets looking for arms which the government refused to give them. In the end they stormed the barracks, and took what they needed. The Republicans were supported by the European left and the Soviet Union, while the Nationalists were armed and equipped by the Fascist governments of Germany and Italy.

The Spanish Civil War would prove not only both tragic and bloody, but also as David Sanders writes:

..retained an evocative quality which the other crises preceding World War II lack. Although its concrete result was a fascist triumph, it also offered international communism its greatest political opportunity since the Soviet revolution by converting the concept of a united front against fascism from a topic for discussion to battlefield reality. And, long before the surrender of of Madrid, it had inspired an impressive literature, even though party line reportage must be entered into the canon with Man's Hope and For Whom the Bell Tolls.Studying the amazing works of the graphic artists who dealt with the Spanish civil war, and here we can see the works of artists both, the Nationalist and the Republican, sides, it would be very difficult to disagree with Hemingway's profound judgement.

The inescapable relationship between politics and writing in this war is, of course, the obscuring factor in judging the real worth of its literature . This problem of how far communist objectives came to be shared by noncommunist writers may be seen most clearly in the relevant works of Ernest Hemingway. No other writer, so involved , was more provably noncommunist than the author of Green Hills of Africa, yet none was to call more urgently for militant struggle against fascists. Twenty years later, Hemingway, of all American writers dealing with the struggle, has been most consistently faithful to his early convictions."

|

|

|

| To speak of the Falange is to name Spain |

No comments:

Post a Comment