The graphic design of the native American pottery is original and almost always symbolic . Technically, all known Pre-Colombian American pottery was made entirely by hand and there is no evidence that a native American potter ever invented the potter's wheel.

History

Native Americans entered the continental United States from Asia, traveling across the Bering Strait and through Canada, between 25th to 8th millennium B.C., when a land path existed. At the beginning of the agriculture era in North America, at about first century AD, the native hunters, who had a nomadic life style, settled down around their farms. The new life style required vessels for gathering water and storing grains, wine and oils, and thus they developed pottery. The designs were different at different communities according to the creativity of various artists and to the extent that they wanted to adhere to their legends and customs as well as according to their ingenuity in solving the technical problems of gathering and storing water. Native villages all over the continent developed their unique styles. Because their cultural respects for the artistic talent of their women, native women became the chief pottery makers.

The stalling culture, on Stalling Island near Augusta, Georgia, has produced the oldest documented pottery in North America. Its archaeological site has been the source of study and conjecture by archaeologists since 1873. They speculate that the origins of the culture began about 5,000 years ago in the Lower Savannah River Valley. Nevertheless, the most widely known Native American pottery is from the civilizations of the American southwest. It is not yet known if the US southeast pottery making was brought by immigrant indigenous peoples from other areas or if it originated independently.

Ceramics from northern Florida cultures date to 2,460 BC. Ceramics of these cultures are all older than any other dated ceramics from north of Colombia, Brazil. Ceramics appeared later elsewhere in North America reaching southern Florida (Mount Elizabeth) by 2000 BC, Nebo Hill (in Missouri) by 1750 BC, and Poverty Point (in Louisiana) by 1450 BC. Two major pottery types appeared in the eastern United States. Ceramic pieces found in Nebo Hill, Missouri date to 1,750 BC. It is believed that pottery making in the southwestern United States came to the Chaco area, in what is now New Mexico, from Central America. The oldest known pottery from this area is only about 3,600 years old. The descendants of those people, the Anasazi, then migrated over large areas carrying the tradition of pottery making with each settlement and personalizing the end result.

Early Native American pottery, such as that made by the Hopi, used basic designs with crude decorations. Other tribes, such as the Anasazi, created white pottery with black designs. It was discovered that different types of wood used for firing pottery would create different colors, such as orange and yellow. The Sikyatki style of Native American pottery introduced geometric designs and included images of nature.

History

Native Americans entered the continental United States from Asia, traveling across the Bering Strait and through Canada, between 25th to 8th millennium B.C., when a land path existed. At the beginning of the agriculture era in North America, at about first century AD, the native hunters, who had a nomadic life style, settled down around their farms. The new life style required vessels for gathering water and storing grains, wine and oils, and thus they developed pottery. The designs were different at different communities according to the creativity of various artists and to the extent that they wanted to adhere to their legends and customs as well as according to their ingenuity in solving the technical problems of gathering and storing water. Native villages all over the continent developed their unique styles. Because their cultural respects for the artistic talent of their women, native women became the chief pottery makers.

The stalling culture, on Stalling Island near Augusta, Georgia, has produced the oldest documented pottery in North America. Its archaeological site has been the source of study and conjecture by archaeologists since 1873. They speculate that the origins of the culture began about 5,000 years ago in the Lower Savannah River Valley. Nevertheless, the most widely known Native American pottery is from the civilizations of the American southwest. It is not yet known if the US southeast pottery making was brought by immigrant indigenous peoples from other areas or if it originated independently.

Ceramics from northern Florida cultures date to 2,460 BC. Ceramics of these cultures are all older than any other dated ceramics from north of Colombia, Brazil. Ceramics appeared later elsewhere in North America reaching southern Florida (Mount Elizabeth) by 2000 BC, Nebo Hill (in Missouri) by 1750 BC, and Poverty Point (in Louisiana) by 1450 BC. Two major pottery types appeared in the eastern United States. Ceramic pieces found in Nebo Hill, Missouri date to 1,750 BC. It is believed that pottery making in the southwestern United States came to the Chaco area, in what is now New Mexico, from Central America. The oldest known pottery from this area is only about 3,600 years old. The descendants of those people, the Anasazi, then migrated over large areas carrying the tradition of pottery making with each settlement and personalizing the end result.

|

| Florida's Native Pottery Types |

Early Native American pottery, such as that made by the Hopi, used basic designs with crude decorations. Other tribes, such as the Anasazi, created white pottery with black designs. It was discovered that different types of wood used for firing pottery would create different colors, such as orange and yellow. The Sikyatki style of Native American pottery introduced geometric designs and included images of nature.

Most terracotta pottery requires the use of a tempering agent , which consists of small pieces of solid material, to lessen the effects of heat and shrinkage on the clay. Native Americans used a variety of tempering agents over the past two millennia or so when they fired clay vessels. In general, the early temperaments consisted of pieces of crushed rock such as igneous or metamorphic rocks, sand and even limestone. While rock is of good temper and performed well during firing and use, pots with rock temper tend to be brittle and therefore shattered into small shards. From AD 1000, Native Americans began to use crushed freshwater bivalve shells to temper their pots. At first they added rock to the shell mix, but over time the shell alone became the preferred temperament. Because the shell is lenticular (in thin lenses), thinner, stronger pots could be made.

The early surfaces of Native American pots, although corded or rough, were generally simple and minimalist. Plain pots aren't as common as corded pots, but most pots will feature a combination of smooth and corded areas, like a smooth neck with a corded body. The marking of the cords makes the surface rough for easier handling and also allows for better heat transfer to the pan when cooking.The Spanish missionaries influenced Native pottery design, and new techniques were learned, such as glazing.

Some of the oldest pottery in North America has been found along the Savannah River in Georgia and South Carolina. The design of this pottery is generally minimalist with some simple decoration being paddled or rolled textures. The designers use their local terra cotta form of ceramics, usually wood fired in the pit method. As time passed, new techniques were discovered and primarily in the Mississippian period decoration began to get more elaborate, with iron slips being created from grinding of iron ore rich rocks being ground up in mortals and pestles and designs being painted on the outside of the pots.

Mimbres Pottery

The Mimbres were part of a larger group known as the Mogollon who settled around the somewhat isolated mountain and river valleys of southwestern New Mexico from about the 11th to the mid-13 th century. They were concentrated around the Mimbres River, which was named by early Spanish settlers for the abundance of mimbres or small willows found along its banks. Walter Fewkes (1850-1930) was the first researcher who classified the Mimbres designs painted on the pottery. According to his classification there were three types of designs; geometric, conventionalized, and realistic. Fewkes also identified a number of graphic design themes within these categories, including: human figures performing various activities; the representation of multiple animals ranging from realistic to whimsical; and varied geometrical designs ranging in complexity. Subsequent researchers have extended Fewkes' classification and have introduced more refind stylistic design systems.

Sources of Inspiration and techniques,

Art and religion are integral to all Native American indigenous peoples that come from many cultural groups and more than 500 tribal nations. They create designs that have been described as bold and imaginative graphic designs in both ceremonial and utilitarian objects.

The Nazca natives of Peru are best known for their polychrome pottery, with colorful graphic designs. The term Nazca refers to the archaeological culture flourished from the first to eighth centuries AD beside the dry southern coast of Peru in the river valleys of the Rio Grande de Nazca drainage and the Ica valley. Having been heavily influenced by the preceding Paracas culture, which was known for extremely complex textiles, the Nazca produced an array of beautiful crafts and technologies including ceramics. The Nazca pottery is characterized by its beautiful polychrome of at least 15 distinct colors. The shift from post-fire resin painting to pre-fire slip painting marked the end of Paracas style and the beginning of Nazca style pottery. The use of pre-fire slip painting meant that a great deal of experimentation took place in order to know which slips produced certain colors.

The customary method of interring the dead of the ancient people of the coast provinces of Ecuador was urn burial. In the ruins of Manta cemetery great quantities of potsherds of a red ware are scattered over the ground. These fragments are thick and massive, showing that they are the remains of large urns. This was the location of the ancient temple where the remains of many large jars were found while grading for the cemetery.The greater number of pottery objects are found in regions where the burials were rather near the surface, and they are brought to light by the plough and the frequent washouts which occur during the rainy season .

Firing of Narino vessels seems to have been done by the open pit or hearth method. One clue to the conditions of firing is the extreme variability of the color of the paste within a given ceramic complex. Control of oxygen was apparently not good since many vessels seem to have been unintentionally reduced and there is also a very high percentage of fire, eluded vessels.

Finishing techniques include scraping, wiping, burnishing, polishing, and retouching of modeled features. All coiled vessels were scraped to obliterate the coil joins and then wiped. Burnishing seems to have been done with a small stone or, perhaps, an animal tooth since the strokes are generally quite narrow. Most of the slip painted wares are polished on the decorated surface. The damp vessel was rubbed to a high gloss, probably with the same sort of tool used for burnishing. Generally only the decorated surface is polished. Slip painting in shades of red and orange and white is found throughout the valley. The exact shades of color vary, presumably with the source of the clay for slip, but in general painted vessels are given a coat of slip of a redder color than the paste.

The ceramic art of West Mexico is among the finest made in the ancient Americas. Over 2,000 years ago, creative ceramicists achieved technical and artistic excellence in modeling and baking clay, and in creating exquisite surface finishes and compelling detail. In a society that lacked a writing system, the spectrum of outstanding ceramic art from West Mexico bears witness to the culture and achievements of its fascinating people.

Buried in underground shaft tombs, the ceramic art of West Mexico lay hidden and protected for hundreds of years. In the late-1800s, European explorers such as Adela Breton and Carl Lumholtz first brought outside attention to West Mexico's striking ceramic art. It was Mexico's great artist couple, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, who in the early 20th century began collecting West Mexican ceramic art. Their passion and knowledge gave immediate stature to the ceramic art of ancient West Mexico.

Teotihuacan was dedicated to Tlaloc, the water god, and originally Quetzalcoatl, as a snake, is representation of the fertility of the earth, was subordinate to him, and the feathers make him a celestial being, a representations of the winds that bring the rain. In time Quetzalcoatl was mixed with other gods, and acquired their attributes. Quetzalcoatl is often asociated with Ehecatl, the wind god, and represents the forces of nature, and is also associated with the morning star (Venus). Quetzalcoatl became a representation of rain, the celestial water and their asociated winds, while Tlaloc would be the god of the earthly water, the water in the lakes, caverns, rivers and also of the vegetation. Eventually Quetzalcoatl was transformed into one of the gods of the creation (Ipalnemohuani).

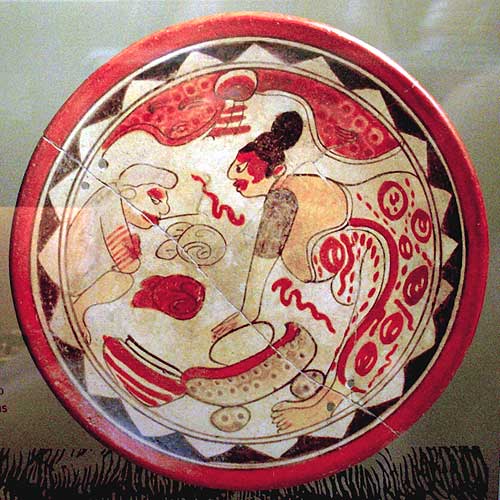

Large Maya Swimmer bowl from El Salvador (550 AD - 900 AD). Exterior has a lower band of two prone figures thought to represent the Hero Twins "Hunahpu" and "Xbalanque" on their journey through Xibalba, the Maya Underworld. An upper band of nicely detailed Copador glyphs around the rim. The interior has a band of repeating glyphs and concentric circles. Painted in red, orange and black over cream.

Mesoamerican pottery has some great traditions. Not only did the various Mesoamerican cultures make and use very utilitarian vessels for food storage and cooking, but they also made more ceremonial vessels, funerary urns, and figures. The term "Mesoamerica" itself gives a clue to the interrelated styles and motifs we will find. Pre-columbian archeology sees Mesoamerica as a culturally-related area comprising the southern states of Mexico and the countries of Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, western Honduras and Nicaragua, and northwestern Costa Rica.

Cocoa was of significant importance in Mesoamerican cultures, to the extent that the Mayan civilization worshiped the cacao tree and believed that cacao was the food of the gods. Cacao even had a specific deity, Ek-chuah, to watch over the trees, pods, and preparation. Cacao pods were used in the Mayan rituals and ceremonies.

Go to the next chapter; Chapter 14 - The Mayan, Aztecs, Incas, and the Aboriginal Canadian Art

Go to the next chapter; Chapter 14 - The Mayan, Aztecs, Incas, and the Aboriginal Canadian Art

- Coe, Michael, (1999) ''The Maya'' (6th ed.), Thames and Hudson: New York. Miller, Mary Ellen (1999) ''Maya Art and Architecture'', Thames and Hudson: New York. Reents-Budet, Dorie, et al. (1994) ''Painting the Maya Universe: Royal Ceramics of the Classic Period'', Duke University Press: Durham, NC and London.

- http://museum.stanford.edu/view/native_america.html Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Stanford University, California, USA]

- Frederick Webb Hodge, Editor, Notched Plate of Stone from Mississippi , With Artistic Engraving of Feathered Rattlesnakes. 1907

- Jesse Walter Fewkes, Designs on Prehistoric Pottery from the Mimbres Valley, New Mexico (1925)

- Allen, Catherine J., ''The Nasca Creatures: Some Problems of Iconography''. Anthropology, 1981, Stony Brook: Department of Anthropology, State University of New York-Stony Brook. Carmichael, Patrick, Interpreting Nasca Iconography. in Ancient Images, Ancient Thought: The Archaeology of Ideology, 1992, Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Chacmool Conference, University of Calgary. Calgary: Department of Archaeology, University of Calgary.

- Brody, J.J. , Mimbres Painted Pottery. School of American Research: Santa Fe, New Mexico. 1977.

- Brody, J.J., Steven A. Leblanc, and Catherine J. Scott

Mimbres Pottery: Ancient Art of the Southwest. NY: Hudson Hills Press, 1983. - Creel, Darrell

Excavations at the old Town Ruin, Luna County, New Mexico, 1989-2003. Cultural Resource Series No. 16, New Mexico Bureau of Land Management. 2006 - Fewkes, J. Walter , Archaeology of the Lower Mimbres Valley, New Mexico. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1914.

- Fewkes, J. Walter , Designs on Prehistoric Pottery from the Mimbres Valley, New Mexico. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Vol. 74, No. 6, pp 1-47, 1925

- Hegman, Michele, Recent Issues in the Archaeology of the Mimbres Region of the North American Southwest. Journal of Archaeological Research Vol 10, No. 4, December 2002.

- Leblanc, Steven A. , The Mimbres People: Ancient Pueblo painters of the American Southwest. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1983.

- Munson, Marit K. , Sex, Gender, and Status: Human Images from the Classic mibres. American Antiquity 65(1): 127-143, 2000.

- Shafer, Harry J. and Robbie L. Brewington, "Microstylistic Changes in mimbres Black-on-White Pottery: Examples from the NAN Ruin, Grant County, New Mexico" 1995. Kiva 64(3): 5-29.

- Shafer, Harry J. , 2003 Mimbres Archaeology at the NAN Ranch Ruin. University of New Mexico Press.

- Steinbach, Tom Sr. , Mimbres Classic Mysteries: Reconstructing a Lost Culture Through its Pottery. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2002.

- Woosley, Anne I. and Allen J. McIntyre. Mimbres Mogollon Archaeology. Amerind Foundation, Archaeology Series No. 10, 1996.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License.

No comments:

Post a Comment