During the 19th century many artists looked at their art as a means for social change and correcting the ills and injustices of the society. Inspired by the ideas of enlightenment, they were taking the role of social critics. They were influenced by the values of modernity and enlightenment. Such values were in stark contrast to those of society at large. Poster art as social commentary was introduced by artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Theophile Steinlen, and Leonetto Cappiello . They assumed the roles of reporter and analyst in an exploration of their era and their society. Their subjects ranged from the daily struggles of working poor, the scenes in brothels, the lifestyles of addicts and outcasts and the hardships of the old and humble. It appears that these artists wished to analyze the social fabric of society and draw conclusions, perhaps for changing it. Their art appears to be critical of socio-economic structures which are seen as harmful, but it also celebrates the simple joys of humanity and somehow poeticize everyday life.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) was born as the son of an aristocratic and rich family in the South of France. From early childhood he developed a passion for drawing and painting and received painting and drawing lessons by a professional artist, Rene Princeteau. He went to Paris in 1882 to study painting, where he met Émile Bernard and Vincent van Gogh . He became attracted to the Impressionist style and joined the movement. Lautrec became a part of the bohemian community of Montmartre with its nightlife of cabarets, cafes, restaurants, sleazy dance halls and brothels. Lautrec, was deeply influenced by Japanese woodblock printing. From the 1850s onwards, Japanese art work flowed into the west and attracted the attention of both artists and collectors. The term "japonisme" was coined in 1872 by Philippe Burty, a French art critic.

Lautrec lived during the height of what have been called 'La Belle Époque' of Paris. Although his handicap and his alcohol abuse kept him from enjoying some of life's pleasures. He applied Cheret's style to depict the nightlife of Montmartre. Although Lautrec was not the only poster artist that used Montmartre as a backdrop to his work, as some of Cheret's pupils, such as Georges Meunier in his poster L'Elysee Montmartre (1895), and Lucien Lefevre in Electricine (1895) have already done so, his however revolutionized Cheret's style in that they were social commentaries of his era. His posters were bold, and his aesthetics avant-garde with a radically flattened space, satirical characters with virtually no graduated shading, Japanese-inspired simplifications, clear silhouettes, and stark colors.

The ideal, elegant, and joyful women of Jules Chéret were replaced in Lautrec's posters by prostitutes and madams who accepted him as a fellow outcast, and permitted him to wander about, sketching and painting freely on his own initiative or on commission to the brothels. He grew close to his prostitute models; he played games with them, brought them presents, and accompanied them to his studio, restaurants, circuses, or theaters during their time off. He neither vilified nor glamorized these women, but presented an objective, almost documentary view of the everyday life they shared with him. According to André Mellerio: Lautrec

Lautrec gradually reduced the role of text in his posters. His last poster has all the necessary information captured by the name of the dancer; Jane Avril (1893).

Theophile Alexandre Steinlen or 'Theophile Steinlen' (1859-1923) was born in Switzerland, where he studied art at Lausanne and later became active as a textile designer in Mulhause. Mainly self-taught, he arrived in Paris at the age of twenty three in 1882. He quickly established himself as a leading illustrator of popular journals such as Le Rire, Mirliton, Assiette au Beurre, Chat Noir, and Gil Blas, for which he produced over four hundred lithographs. As an artist he was not merely a commercial success but showed great sensitivity toward social issues. Besides illustrating advertisements for a variety of products, Steinlen was famous for his posters of cabaret and music hall performers. He also contributed a large amount of drawings and lithographs to the radical press publications, Pere Peinard, Les Temps Nouveaux and La Chambard. In order to avoid political repercussions for some of his art dealing with strong social content he often employed pseudonyms such as, 'Treelan' and 'Pierre'. Steinlen's contributions to the Socialist journal, La Chambard, were particularly influential. He was a regular artist for this publisher during the years of 1893 and 1894.

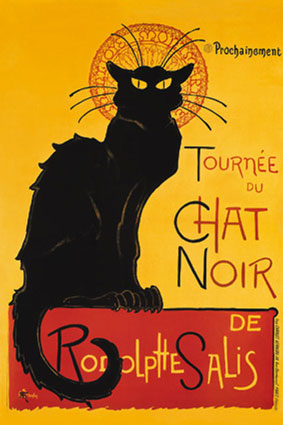

Steinlen's lithographs were reproduced upon thin newsprint in the journal by photography and typography with added captions. Steinlen's images were critica of social contrasts, which he depicted with a sure handed simplicity, fine imagery and stylistic elegance. Theophile Steinlen's wonderful use of line and design led to some of the most famous posters of his era. These include, Tournee du Chat Noir (1896), La Rue (1896) and Lait pur Sterilise (1894). Yet the majority of his great art continued to explore the living struggles of the working class . Known as "the Millet of the Streets", Theophile Steinlen's influence was vast. Among other artists both Toulouse-Lautrec and the young Picasso paid direct homage to his art.

Some of Theophile Steinlen's most famous lithographs from Le Chambard were published in limited editions of one hundred impressions on high quality paper by Kleinmann in Paris. From 1893 to 1895 this publisher also commissioned lithographic art from Toulouse-Lautrec, Cheret, Forain, Grasset, Vallatton and others. Most of the original lithographs published by Kleinmann bear his blindstamp and publication number in red pencil in the extreme lower left margin. In total, Theophile Alexandre Steinlen created 382 original lithographs and 115 etchings.

Leonetto Cappiello (1875-1942) was born in Livorno, Italy. He had no formal training. In 1898, he decided to visit Paris, and immediately fell in love with the city and decided to stay. He did two sketch caricatures of his compatriots, the actor Novelli and the composer Puccini and submitted them to "Le Rire," a popular humour magazine. They wre accepted, and he became an overnight sensation. His career for "Le Rire," earned him resulted in his first poster commission and by in 1900 his posters were in high demand. He was influenced by Cheret, but anticipating a more modern approach to poster design, his work incorporated a sophisticated simplification which abstracted from unnecessary details, and concentrating on a dynamic composition.

In fact, his was the first posters that recorded the quickening pace of life in the streets as the new era of automobiles took hold. He is called "The Father of modern advertising," and his posters exhibited a profound understanding of the subtle communication techniques. For instance his famous 1894 design for Absinthe Parisienne by P. Gélis-Didot and Louis Malteste depicts a coyish erotic message, subtilely suggesting in its text "Bois donc, tu verras après..." (Drink - then you'll see...) .An overly self-assured male character, based on Molière's comic doctor Diafoirus, is enticing an apparently chaste redhead, whose body language projects a pretense to innocence.

Cappiello's portraits and posters were mischievous, cheerful and uncommon. His compositions were strong, harmonious and balanced. Because of his minimalism approach, Cappiello was able to produce nearly 1000 posters in his time.

By 1920s the idea of graphic arts as a vehicle for social commentary had gained a solid ground throughout Europe. Artists became more daring in their experimentation and as consequence they revolutionized the grammar and the vocabulary of the communication design discipline. The graphic arts became a mixture of bold and innovative typefaces, elaborate collages, and experimentation with geometrical illustration, and architectural rendering sometimes with a playful bawdiness and irreverence. Graphic artists like John Heartfield, who changed his name from Hertzfeld in protest against German war machine, revolutionized typography and created the first photomontage. He became a member of the Berlin dada and eschewed the title of artist in favour of monteur which mean engineer. Many artists followed suit abandoning aesthetic approach in favour of collage and functionality, trying to reinterpret the reality of the new age. Their assemblage of new materials introduced some powerful elements of subjectivity into the visual communication design.

Whereas some Russian visual designers like Malevich and Kandinsky, argued that art must remain an essentially spiritual activity apart from the utilitarian needs of society, and rejected a social or political role, believing the sole aim of art to be realizing perceptions of the world by inventing forms in space and time others led by Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953) and Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956), advanced the opposing viewpoint. Renouncing "art for art's sake", these constructivists devoted themselves to industrial design, visual communications, and applied arts serving the new communist society.

They called on the artist to stop producing useless things such as paintings and turn to the poster, for "such work now belongs to the duty of the artist as a citizen of the community who is clearing the field of the old rubbish in preparation for the new life." They considered propaganda ethical as long as it would serve to establish a modern society, many sculptors, architects, photographers, filmmakers, and set designers joined this movement, among them were Stenberg brothers.

The brothers were born in Moscow, Vladimir in 1899, Georgi in 1900. Their father was Swedish who married their Russian mother. After studying engineering, they become active in revolutionary art, contributing to manifestos from Moscow's new cafe commissars which read:''Constructivism will enable mankind to achieve the maximum level of culture with the minimum expense of energy,''. They created film posters, which was considered an ideal medium for a constructivists since it involved mass production, a conduit for communicating with masses, and it was linked to the modern technology of cinema. Beginning in 1923, the Stenbergs made many imaginative and bold posters. They also landed commissions that ranged from railway cars to women's shoes, but their most significant contribution was in the field of visual communication design, particularly their movie posters. The film posters of the Stenberg bothers, produced from 1923 until Georgii's untimely death in 1933, represent an uncommon synthesis of the philosophical, formal, and theoretical elements of what has become known as the Russian avant-garde.

Their posters, avant-garde even by today's standards, are born out of their aestheticizing impulse, which at the same time that try to sell specific movies tend to develop an independent existence as visual communication art rooted in the hermetic discourse of the fine arts, with a hostile tendency to artistic traditions and popular culture. They exploited their intimate knowledge of contemporary avant grade movements, which were deteriorating into something much too close to a reactionary "commodity aesthetics" to create a bold advertising technique that put more traditional ideas about both advertising and the avant-garde into question.

The Stenberg's functionalism may be detected as inherent in the totality of their design actions - the drastic conceptual change the film poster, the dynamic geometry of composition, the purposeful utilization of typography and color, the reformulation of scale and perspective -taken to produce a desired effect. Their complete rethinking of the production of posters, and experimentation with photographic images and letterforms anticipates the revolutionary charges of digital technology. The Stenberg's posters have affected the architecture and aesthetics of visual design. Their posters are a reminder of what the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss has terned bricolage, their process of creating a poster is not a matter of the calculated choice and use of whatever materials are technically best-adapted to a clearly predetermined purpose, but rather it involves a 'dialogue with the materials and means of execution' (Lévi-Strauss 1974, 29). In such a dialogue, the materials which are ready-to-hand may (as we say) 'suggest' adaptive courses of action, and the initial aim may be modified. Consequently, such acts of creation are not purely instrumental: the bricoleur '"speaks" not only with things... but also through the medium of things'(ibid., 21): the use of the medium can be expressive. Their elasticity and the pure anatomy of compositions creates astonishing results without fitting together harmoniously. Often enigmatic, with subtle sense of humor, and emtionally complex, the arrangement of these basic elements in a visual space, leads to the field of visual thinking and forms their basic grammar of visual communication.

Go to the next chapter; Chapter 29 -- Propaganda Posters

References

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) was born as the son of an aristocratic and rich family in the South of France. From early childhood he developed a passion for drawing and painting and received painting and drawing lessons by a professional artist, Rene Princeteau. He went to Paris in 1882 to study painting, where he met Émile Bernard and Vincent van Gogh . He became attracted to the Impressionist style and joined the movement. Lautrec became a part of the bohemian community of Montmartre with its nightlife of cabarets, cafes, restaurants, sleazy dance halls and brothels. Lautrec, was deeply influenced by Japanese woodblock printing. From the 1850s onwards, Japanese art work flowed into the west and attracted the attention of both artists and collectors. The term "japonisme" was coined in 1872 by Philippe Burty, a French art critic.

Lautrec lived during the height of what have been called 'La Belle Époque' of Paris. Although his handicap and his alcohol abuse kept him from enjoying some of life's pleasures. He applied Cheret's style to depict the nightlife of Montmartre. Although Lautrec was not the only poster artist that used Montmartre as a backdrop to his work, as some of Cheret's pupils, such as Georges Meunier in his poster L'Elysee Montmartre (1895), and Lucien Lefevre in Electricine (1895) have already done so, his however revolutionized Cheret's style in that they were social commentaries of his era. His posters were bold, and his aesthetics avant-garde with a radically flattened space, satirical characters with virtually no graduated shading, Japanese-inspired simplifications, clear silhouettes, and stark colors.

The ideal, elegant, and joyful women of Jules Chéret were replaced in Lautrec's posters by prostitutes and madams who accepted him as a fellow outcast, and permitted him to wander about, sketching and painting freely on his own initiative or on commission to the brothels. He grew close to his prostitute models; he played games with them, brought them presents, and accompanied them to his studio, restaurants, circuses, or theaters during their time off. He neither vilified nor glamorized these women, but presented an objective, almost documentary view of the everyday life they shared with him. According to André Mellerio: Lautrec

smells a vague stench of moral corruption and captures its effect without naming it, and does it without seeming to place the blame. One almost gets the feeling he experiences a kind of bitter pleasure from soaking up this aroma ... If M. de Toulouse-Lautrec’s art is not uplifting in terms of virtue overcoming vice, at least he has analyzed vice with a highly unusual degree of perceptiveness.

Lautrec gradually reduced the role of text in his posters. His last poster has all the necessary information captured by the name of the dancer; Jane Avril (1893).

Theophile Alexandre Steinlen or 'Theophile Steinlen' (1859-1923) was born in Switzerland, where he studied art at Lausanne and later became active as a textile designer in Mulhause. Mainly self-taught, he arrived in Paris at the age of twenty three in 1882. He quickly established himself as a leading illustrator of popular journals such as Le Rire, Mirliton, Assiette au Beurre, Chat Noir, and Gil Blas, for which he produced over four hundred lithographs. As an artist he was not merely a commercial success but showed great sensitivity toward social issues. Besides illustrating advertisements for a variety of products, Steinlen was famous for his posters of cabaret and music hall performers. He also contributed a large amount of drawings and lithographs to the radical press publications, Pere Peinard, Les Temps Nouveaux and La Chambard. In order to avoid political repercussions for some of his art dealing with strong social content he often employed pseudonyms such as, 'Treelan' and 'Pierre'. Steinlen's contributions to the Socialist journal, La Chambard, were particularly influential. He was a regular artist for this publisher during the years of 1893 and 1894.

Steinlen's lithographs were reproduced upon thin newsprint in the journal by photography and typography with added captions. Steinlen's images were critica of social contrasts, which he depicted with a sure handed simplicity, fine imagery and stylistic elegance. Theophile Steinlen's wonderful use of line and design led to some of the most famous posters of his era. These include, Tournee du Chat Noir (1896), La Rue (1896) and Lait pur Sterilise (1894). Yet the majority of his great art continued to explore the living struggles of the working class . Known as "the Millet of the Streets", Theophile Steinlen's influence was vast. Among other artists both Toulouse-Lautrec and the young Picasso paid direct homage to his art.

Some of Theophile Steinlen's most famous lithographs from Le Chambard were published in limited editions of one hundred impressions on high quality paper by Kleinmann in Paris. From 1893 to 1895 this publisher also commissioned lithographic art from Toulouse-Lautrec, Cheret, Forain, Grasset, Vallatton and others. Most of the original lithographs published by Kleinmann bear his blindstamp and publication number in red pencil in the extreme lower left margin. In total, Theophile Alexandre Steinlen created 382 original lithographs and 115 etchings.

Leonetto Cappiello (1875-1942) was born in Livorno, Italy. He had no formal training. In 1898, he decided to visit Paris, and immediately fell in love with the city and decided to stay. He did two sketch caricatures of his compatriots, the actor Novelli and the composer Puccini and submitted them to "Le Rire," a popular humour magazine. They wre accepted, and he became an overnight sensation. His career for "Le Rire," earned him resulted in his first poster commission and by in 1900 his posters were in high demand. He was influenced by Cheret, but anticipating a more modern approach to poster design, his work incorporated a sophisticated simplification which abstracted from unnecessary details, and concentrating on a dynamic composition.

In fact, his was the first posters that recorded the quickening pace of life in the streets as the new era of automobiles took hold. He is called "The Father of modern advertising," and his posters exhibited a profound understanding of the subtle communication techniques. For instance his famous 1894 design for Absinthe Parisienne by P. Gélis-Didot and Louis Malteste depicts a coyish erotic message, subtilely suggesting in its text "Bois donc, tu verras après..." (Drink - then you'll see...) .An overly self-assured male character, based on Molière's comic doctor Diafoirus, is enticing an apparently chaste redhead, whose body language projects a pretense to innocence.

Cappiello's portraits and posters were mischievous, cheerful and uncommon. His compositions were strong, harmonious and balanced. Because of his minimalism approach, Cappiello was able to produce nearly 1000 posters in his time.

Stenberg Brothers

By 1920s the idea of graphic arts as a vehicle for social commentary had gained a solid ground throughout Europe. Artists became more daring in their experimentation and as consequence they revolutionized the grammar and the vocabulary of the communication design discipline. The graphic arts became a mixture of bold and innovative typefaces, elaborate collages, and experimentation with geometrical illustration, and architectural rendering sometimes with a playful bawdiness and irreverence. Graphic artists like John Heartfield, who changed his name from Hertzfeld in protest against German war machine, revolutionized typography and created the first photomontage. He became a member of the Berlin dada and eschewed the title of artist in favour of monteur which mean engineer. Many artists followed suit abandoning aesthetic approach in favour of collage and functionality, trying to reinterpret the reality of the new age. Their assemblage of new materials introduced some powerful elements of subjectivity into the visual communication design.

Whereas some Russian visual designers like Malevich and Kandinsky, argued that art must remain an essentially spiritual activity apart from the utilitarian needs of society, and rejected a social or political role, believing the sole aim of art to be realizing perceptions of the world by inventing forms in space and time others led by Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953) and Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956), advanced the opposing viewpoint. Renouncing "art for art's sake", these constructivists devoted themselves to industrial design, visual communications, and applied arts serving the new communist society.

They called on the artist to stop producing useless things such as paintings and turn to the poster, for "such work now belongs to the duty of the artist as a citizen of the community who is clearing the field of the old rubbish in preparation for the new life." They considered propaganda ethical as long as it would serve to establish a modern society, many sculptors, architects, photographers, filmmakers, and set designers joined this movement, among them were Stenberg brothers.

The brothers were born in Moscow, Vladimir in 1899, Georgi in 1900. Their father was Swedish who married their Russian mother. After studying engineering, they become active in revolutionary art, contributing to manifestos from Moscow's new cafe commissars which read:''Constructivism will enable mankind to achieve the maximum level of culture with the minimum expense of energy,''. They created film posters, which was considered an ideal medium for a constructivists since it involved mass production, a conduit for communicating with masses, and it was linked to the modern technology of cinema. Beginning in 1923, the Stenbergs made many imaginative and bold posters. They also landed commissions that ranged from railway cars to women's shoes, but their most significant contribution was in the field of visual communication design, particularly their movie posters. The film posters of the Stenberg bothers, produced from 1923 until Georgii's untimely death in 1933, represent an uncommon synthesis of the philosophical, formal, and theoretical elements of what has become known as the Russian avant-garde.

Their posters, avant-garde even by today's standards, are born out of their aestheticizing impulse, which at the same time that try to sell specific movies tend to develop an independent existence as visual communication art rooted in the hermetic discourse of the fine arts, with a hostile tendency to artistic traditions and popular culture. They exploited their intimate knowledge of contemporary avant grade movements, which were deteriorating into something much too close to a reactionary "commodity aesthetics" to create a bold advertising technique that put more traditional ideas about both advertising and the avant-garde into question.

The Stenberg's functionalism may be detected as inherent in the totality of their design actions - the drastic conceptual change the film poster, the dynamic geometry of composition, the purposeful utilization of typography and color, the reformulation of scale and perspective -taken to produce a desired effect. Their complete rethinking of the production of posters, and experimentation with photographic images and letterforms anticipates the revolutionary charges of digital technology. The Stenberg's posters have affected the architecture and aesthetics of visual design. Their posters are a reminder of what the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss has terned bricolage, their process of creating a poster is not a matter of the calculated choice and use of whatever materials are technically best-adapted to a clearly predetermined purpose, but rather it involves a 'dialogue with the materials and means of execution' (Lévi-Strauss 1974, 29). In such a dialogue, the materials which are ready-to-hand may (as we say) 'suggest' adaptive courses of action, and the initial aim may be modified. Consequently, such acts of creation are not purely instrumental: the bricoleur '"speaks" not only with things... but also through the medium of things'(ibid., 21): the use of the medium can be expressive. Their elasticity and the pure anatomy of compositions creates astonishing results without fitting together harmoniously. Often enigmatic, with subtle sense of humor, and emtionally complex, the arrangement of these basic elements in a visual space, leads to the field of visual thinking and forms their basic grammar of visual communication.

Go to the next chapter; Chapter 29 -- Propaganda Posters

References

- Ackroyd, Christopher. Toulouse-Lautrec. Chartwell Books, 1989

- Toulouse-Lautrec: the Baldwin M. Baldwin Collection, San Diego Museum of Art. San Diego Museum of Art, 1988, ISBN13: 9780937108079.

- André Mellerio, Le Mouvement Idéaliste en peinture (Paris: Floury, 1896), 35–36, trans. in Murray, Retrospective, 248–49, at 249.

- D'esparbes, Georges et al. Les Demi-cabots, le café concert, le cirque, les forains. Paris, 1896.

- Iskin, Ruth E., Identity and Interpretation: Receptions of Toulouse-Lautrec’s Reine de joie Poster in the 1890s, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide , Volume 8, Issue 1, Spring 2009

- Feinblatt, Ebria & Bruce Davis. Toulouse-Lautrec and his contemporaries: posters of the belle époque from the Wagner Collection. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1985.

- Gauzi , Françoise. Lautrec et son temps. Paris, 1954.

- Schimmel, Herbert D. & Phillip Dennis Cate. The Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and W. H. B. Sands correspondence. New York, 1983.

- Stuckey, Charles F. Toulouse-Lautrec paintings. Art Institute of Chicago, 1979.

- Sugana, G.M. The complete paintings of Toulouse-Lautrec. New York, 1969.

- Adhemar, Jean. Toulouse-Lautrec: his complete lithographs and drypoints. New York, 1965.

- Adriani, Götz. Toulouse-Lautrec. London, 1987. Trans. Sebastian Wormell; first published Cologne, 1986. Adriani, Götz. Toulouse-Lautrec: the complete graphic works; a catalogue raisonné, the Gerstenberg collection. Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1988.

- Castleman, Riva & Wolfgang Wittrock. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, images of the 1890s. Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1985.

- Cate, Phillip Dennis & Patricia Eckert Boyer. The Circle of Toulouse-Lautrec. The Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, 1985.

- Cooper, Douglas. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. New York, 1966.

- Hayward Gallery. Toulouse-Lautrec. New Haven, 1991. Catalogue for an exhibition held at the Hayward Gallery, London, October 10, 1991 through January 19, 1992, and at the Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, February 21 through June 1, 1992.

- Huisman, Philippe & M.G. Dortu. Lautrec by Lautrec. New York, 1968. Trans. Corinne Bellow; first published in France, 1964.

- Weisberg, Gabriel P. et al. Japonisme: the Japanese influence on French art, 1854-1910. Cleveland Museum of Art, 1975.

- Ralph E. Shikes, The Indignant Eye: The Artist as Social Critic, Boston, Beacon Press, 1969,

- Ernest de Crauzat, L'Oeuvre Grave et Lithographie de Steinlen, Paris, Societe de Propagation des Livres d'Art, 1913 (Reprint, 1983).

- Rennert, Jack. Cappiello, the posters of Leonetto Cappiello,Poster Auctions Intl Inc, ISBN 0-9664202-7-6

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License.

Nice

ReplyDelete