-----------

The motives which guide the hands of the sculptors and architects of Black Africa, the strait jacket of ritual and symbolism in which the work of art is confined, the looser framework of institutions which surrounds it, the connection between some works themselves inside a society or from one people to anther - all these factors should be as much subjects study as the actual works themselves. For the arts of the Blacks, just like their ritual, their symbolism, and their social and political organization, are a means of exhibiting a general conception of the universe, its origins, workings, goal and meaning. Marcel Griaule,

Africa is the home to the oldest images in the world. The 1991 discoveries of symbolic geometric designs from Blombos Cave on the southern coast of Africa, in the form of engraved ocher plaques, date back almost as far as the one hundred millennium B.C. The artefacts discovered in Blombos cave were made of the iron ore stone ochre. Small pieces of ochre were first scraped and ground to create flat surfaces. The early artist decorated the stones with a complex geometric array of carved lines. Other finds which indicated a relatively advanced Blombos culture, included ground and polished animal bone tools, dated to the eighty millennium BC, making them some of the oldest bone tools in Africa.

African artifacts are created first and foremost in order to serve particular socio-cultural functions, that are rooted in African philosophical world view. They can therefore only be understood in relation to their original context - in political or spiritual-ritual activities, for example. The motifs are often based on symbolic or cultural ideas rather than natural forms, and their meanings are not necessarily accessible to all members of a given society.

There is a Hegelian misconception in western academia that African culture is just an oral culture. Hegel, thought that the north Africa was "to be attached to Europe," and

"Africa proper, as far as History goes back, has remained-for all purposes of connection with the rest of the World-shut up; it is the Gold-land compressed within itself-the land of childhood, which lying beyond the day of history, is enveloped in the dark mantle of Night. Its isolated character originates, not merely in its tropical nature, but essentially in its geographical condition ". This is why Africa is considered by the western academia to be absent from philosophy.

A Timbuktu Manuscript on Astronomy

Nothing can be further from truth. Timbuktu that was founded in the 11th century by Tuareg nomads as a camp by the Niger river in Mali, West Africa, at the southern tip of the Sahara Desert, and quickly established itself as a trade hub for both north and south traveling caravans is a case in point. Timbuktu flourished as a center of philosophical scholarship from the fourteenth through the sixteenth centuries. Books and libraries evolved into blessed symbols of scholarship.

A west African copy of Qurán

There are thousands of West African manuscripts in varied forms and contents, in Arabic and Ajami (African languages written in Arabic script). The development of these manuscript traditions dates back to the 11th century. In addition to these Arabic and Ajami manuscripts, there have been others written in indigenous scripts. These include those in the Vai script invented in Liberia; Tifinagh, the traditional writing system of the Amazigh (Berber) people; and the N’KO script invented in Guinea for Mande languages. While the writings in indigenous scripts are rare less numerous and widespread, they nonetheless constitute an important component of West Africa’s written heritage. There are manuscripts in history, astronomy and astrology, arithmetic and mathematics, numerology and amulets, politics, health, medicine and religion. Many of the irreplaceable manuscripts and artifacts plundered during colonial times.

Page from an illuminated Qur’an in a style typical of the region of southern Niger, northern Nigeria and Chad, late 18th/early 19th century (British Library Or 16,751)

|

| Three minarets mosque of Endé |

|

| A Toguna, or meeting house of Dogons |

|

| A wall painting in Endé |

|

| A Dogon Carved wooden door |

|

| Dogon Carved wooden posts |

|

| A Dogon Mosque in kani kombolé |

In 2018, a report commissioned by the French president, Emmanuel Macron, and authored by French art historian Bénédicte Savoy and Senegalese writer and economist Felwine Sarr, has recommended that art plundered from sub-Saharan Africa during the colonial era should be returned through permanent restitution. According to the report colonial powers acquired these materials by the “theft, looting, despoilment, trickery and forced consent”. For Instance, the Benin expedition of 1897 was a punitive attack on the ancient kingdom of Benin, famous not only for its huge city and ramparts but its extraordinary cast bronze and brass plaques and statues. The city was burnt down, and the British Admiralty auctioned the booty – more than 2,000 art works – to “pay” for the expedition. The British Museum got around 40% of the haul. None of the artifacts stayed in Africa – they’re now scattered in museums and private collections around the world.

Objects on display in Paris at the Quai Branly Museum, which has 70,000 pieces from sub-Saharan Africa.

A Timbuktu Manuscript on Astronomy

The author discusses how to use the movements of the stars to calculate the beginning of the seasons and how to cast horoscopes, among many other aspects of astronomy. Displayed is a diagram demonstrating the rotation of the heavens.Nasir al-Din Abu al-Abbas Ahmad ibn al-Hajj al-Amin al-Tawathi al-Ghalawi. Kashf al-Ghummah fi Nafa al-Ummah (The Important Stars Among the Multitude of the Heavens),

The 1867 British expedition to the ancient kingdom of Abyssinia – which never fully acceded to colonial control – was mounted to ostensibly free missionaries and government agents detained by the emperor Tewodros II. It culminated in the Battle of Magdala, and the looting of priceless manuscripts, paintings and artifacts from the Ethiopian church, which reputedly needed 15 elephants and 200 mules to carry them all away. Most ended up in the British Library, the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert, where they remain today.

Other African treasures were also taken without question. The famous ruins of Great Zimbabwe were subject to numerous digs by associates of British businessman Cecil Rhodes – who set up the Rhodesia Ancient Ruins Ltd in 1895 to loot more than 40 sites of their gold – and much of the archaeology on the site was destroyed. The iconic soapstone birds were returned to Zimbabwe from South Africa in 1981, but many items still remain in Western museums. Similarly, the Musée du quai Branly, a great treasure house of world ethnography in Paris, holds more than 70,000 objects from Africa. As well, the Ethnological Museum in Berlin's new Humboldt Forum has the second largest collection of "Benin Bronzes," sculptural artifacts looted by the British from the ancient kingdom of Benin. Along with a network of European museums, the Berlin institution has agreed to loan some of the 500-odd objects to a museum in Benin under the auspices of the Benin Dialogue Group. Fortunately, African scholars, particularly in west Africa, have began to reclaim and revive their philosophical heritage.

A stunning West African layout and calligraphy

The origins of African art can be traced back to long before its recorded history. About thirty millennium BC, rock art was used to depict different aspects of life with imagery appearing on rocks. The rock art which includes paintings, drawings and engravings depicts animals and human figures in narrative scenes. In fact Southern Africa is sometimes referred to as one of the richest depositories of prehistoric mural art in the world. There are at least 15,000 discovered San rock, or Bushmen,art sites in South Africa with many more sites that are still undiscovered not only in South Africa but also in the neighboring countries of Swaziland, Lesotho, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Namibia. Later on the rock art of the Sahara in Niger from the fourth millennium B.C. continues this tradition. The earliest known sculptures are from the Nok culture of Nigeria, made around 500 B.C. Along with art of Nubia in the ancient Sudan the cultural arts of the western tribes, ancient Egyptian paintings and artifacts, and indigenous southern crafts also contributed greatly to African art.

One of these sites is the Ukhahlamba Drakensberg Park, which contains many caves and rock-shelters with the largest and most concentrated group of paintings in Africa, made by the San people over a period of 4,000 years. These rock paintings are of exquisite quality that through which San people expressed themselves and their universe more fully to themselves and to others. They depicted their spiritual life and their deepest aspirations. In the mid-17th century, when Europeans first discovered the San rock, they described it as churlish and callow, created by a primitive bushman, who was trying to document his savage life style defined by hunting and endless quarrels. Today, however, we have a better understanding and much more respect for this authentic art form, which often depicts the enigma of surrounding nature with abstract interpretations of animals, plant life, and natural designs and shapes. We admire its powerful aesthetics, balanced compositions and harmonious and elegant color schemes. But, more than that, we respect the artists efforts to communicate with us and share with the posterity their wisdom and their sentiments.

|

The most spectacular discoveries in Libyan desert were made by a Belgian expedition in 1968. Far from the main concentration of sites, they came unexpectedly on a very large shelter, some thirty meters long, that is covered by superb paintings of the late Bovidian Phase that is thought to have commenced about 6000 years ago, some showing humans in the characteristic Karnasahi style The above painting is one example of these paintings, in which the artist exhibt an astonishing sense of perspective and composition.

The geographical area defined as Western Sudan refers to the stretch of savanna in West Africa to the south of the Sahara and to the north of the great forests. Since the early 20th century archaeologists have been making new inroads into understanding of Nubia or 'land of Kush' these were the ancient people of Sudan. From the evidence recorded by Egyptians at about two millennium BC, we can infer that they were a powerful nation until the fourth century B.C., after which they were defeated by Ethiopians. The evidence of their sophisticated culture has been discovered in the archeological sites. Among them the oldest tombs of Kingdom of Qustul. These thirty-three tombs appear in Nubia before the dynastic period. The art of Nubia is characterized by a variety of stylistic tendencies, although there is a general preference for abstract forms.

|

The minimalist approach in the design of this Nubian Vessel is aesthetically powerful and elegant. The artist depicts a rowing boat with multiple oars, ostriches and undulating lines symbolizing water. 3800-3100 B.C.,Nubia Museum, Aswan, Egypt. |

|

| In this eggshell thin, handmade polished ware of Nubian design the artist uses the most simple geometric basket pattern that is painted in red to create a pleasing impact. |

The Dogon art is among the most interesting of African tribal art. Dogons live in Mali, on the cliffs of Bandiagara, a remote area high in the hills. They were rather an isolated community that built their villages on steep mountain cliffs. This protected and preserved their culture up to the present time. They flee from the Mossi kingdom and settled on to the cliffs of Bandiagara in the fourteenth century. Like many other African people Dogon artists tend to favor three-dimensional artworks. The Dogon Art embodies all that is fascinating about Africa; mystical, spiritual, emotive and arresting . It evokes joy, fear, emotional exuberance or startling enigma. It is aesthetically complex , spiritually illuminating, and in its defining features, beautiful beyond measure.

|

| Seated Figure Dogon, Mali, 19th-20th Century, Wood, Private Collection |

The Dogon wood figures, Dege, depicting a man and woman on an altar. Most of these wood figures are dedicated to real or mythical ancestors. Every house dedicates an altar containing figurative sculpture representing their ancestors , known as vageu. Ancestors are envisioned as an animating force governing the land of the living and the realm of the spirits. In this sense they are the guarantor of the harmony in the community affairs. The African style, is neither explicative nor emulous, a statue does not represent or describe an ancestor, rather, it suggests an idealized effigy that eulogizes the power of its élan vital. By disproportionate representations of head and trunk; and sexual organs the African style symbolizes the élan vital and fecundity. The rigid but elastic poses of the figures are the indicative of an impending awakening which is suggested by the emphasis on the angular depiction of elbows and knees. The figures usually exhibit a distant dispositions, that can be interpreted, as a state of equanimity and composure, they are emotionless and do not express any particular countenance.

According to the Dogon legends when the first man died, a wooden sculpture was carved and together with a ceramic bowl were placed on the dead man's roof. The carved figure was to provide shelter for his soul and his élan vital (nyama), which were discharged at his death, and the ceramic bowl for libations. This custom then established for all mankind. Not all of a deceased relatives are commemorated on the family altar (vageu). The souls of dead pregnant women, or dead woman when giving birth are regarded as ominous, and the dark forces that precipitate such fatality are exceptionally hazardous. The souls of such women, called "white women" (yaupilu), are buried in a specific repository cave outside the village, which are supervised by a shaman who acts as intermediary between the natural and supernatural worlds and uses spiritual techniques to heal illness.

"I have felt my strongest artistic emotions when suddenly confronted with the sublime beauty of sculptures executed by the anonymous artists of Africa ... These works of a religious, passionate and rigorously logical art are the most powerful and most beautiful things the human imagination has ever produced." Pablo Picasso

The forested region of the Lower Zaire River is important in the artistic history of black Africa, because it boasts the greatest concentration of maternity figures and stone statuary. The vast Yombe area is the focal point of this region, where various artistic styles are profusely practiced. The representation of motherhood is a distinct motif in the majority of African cultures. The African artist celebrates the fecundity of women and cherishes the love of mythical mother who gave life to humankind. The characters of mother figures are generally composed in a seated or kneeling position with a baby at her laps, breast or on her back. The African artist depicts the motherhood in an idealistic state with an abstraction that emphasizes the life-giving, and life-sustaining features of the character .

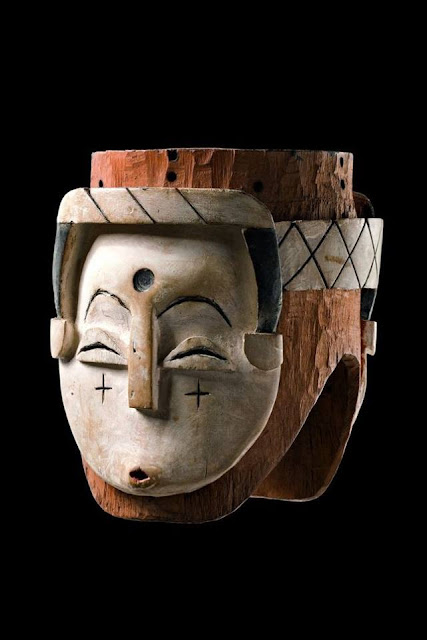

There are more than 60 ethnic groups in Cote D'Ivore, the main ones are the Baoulé in the center, the Agri in the east, the Senufo in the north, the Dioula in the northwest and west, the Bété in the center-west and the Dan-Yacouba in the west. Each one of these groups have their own distinct art. It is said that no one produces a wider variety of masks than the people of the Ivory Coast. Masks are used to represent the souls of deceased people, lesser dieties, or even caricatures of animals. The ownership of masks is restricted to certain powerful individuals or to families. This Baoulé mask is part of ‘portrait masks’ of men and women, Kpan Pre, Kpan Kpan. The masks usually portray a distinguished elder of the village who is celebrated during a ceremonial dance known as “Mblo”. Mblo is an artistic performance in which the guests wear exquisitely carved masks along with a colorful costumes and participate in a ritual dance. The dance celebrates feminine virtues including graceful movements and elegant dancing steps. One of Côte d'Ivoire's most famous festivals is the Fêtes des Masques (Festival of Masks), which takes place in the region of Man occurs in November. Numerous small villages in the region hold contests to determine the best dancers and to pay homage to forest spirits who are embodied in the elaborate masks.

The other important events are the week long carnival in Bouaké each March, and the Fête du Dipri in Gomon, near Abidjan in April. The starts around midnight, when women and children sneak out of their huts and, naked, carry out nocturnal rites to exorcise the village of evil spells. Before sunrise the chief appears, drums pound and villagers go into trances. The frenzy continues until late afternoon of the next day. Only specifically designated, specially trained individuals are permitted to wear the masks. It is believed dangerous for others to wear ceremonial masks because each mask has a soul, or life force, and when a person's face comes in contact with the inside of the mask that person is transformed into the entity the mask represents.

A Gallery of African Masks

The African rock paintings suggest that masks have been used for at least 4,000 years, and yet it is possible that masks of animal heads were used by Paleolithic man at least 35,000 years ago. Nevertheless, the oldest African artifact that is definitely a mask is the highly realistic copper mask of the oni (leader) Obalufon, from the Ife kingdom of Nigeria (12th to 15th century). The eyeholes and the holes in the mask for strings of beads or raffia attachments indicate that it was worn in some ceremony. Wearing their sacred masks during their festivals, African masked performers, usually dancing on stilts, enacted rituals of myth of creation, hero worship, fertility rituals, agricultural festivities, funerals or burials, ancestor cults, and initiations,

Their high priest possessed the masks and guarded them in a sacred hut. Being, in fact, spirits of the wilderness each mask were used for a number of different functions, sometimes as the agents, who intermediates between the village and the forest initiation camp, may prevent bush fires during the dry season, used in pre-war rituals , and for peace-making festivals.

In their spiritual journey to understand the unknown, African artists create the most exquisite stylized designs, with a stunning sense of balanced compositions that are usually unique, with various combinations of curved surfaces, an elongated linear nose, a protruding and sometimes geometric mouth which are often covered in a richly colored patina. The majority of these masks are wood, and mask usage is clearly tied to areas where wood is available. There are symbolic references to the kind of wood used from various trees and the dancers who may often dance in masks taller than their own heights perform their rituals with utmost conviction . The use of raffia attachments add to the aesthetics of the mask in an artistically elegant way.

The carving of the masks are mostly done with a large long-handled axe known as an adze. The African carver is able to acquire amazing accuracy with this large instrument, and even though he has double-edged knives and chisels for fine detailing, the majority of the work is handled with the adze. To some extent, the use of better technology is not welcome for something that has ritual purpose.

Various cultures specialize in different materials for their masks - Basketwork in the Congo, Bronze masks of the Senufo, or metal surfacing among the Marka. African authentic carvers have also been resourceful in the many materials they might include on the mask, like sheet metal, fur, animal teeth, cock`s feather, human hair, textile, glass, cowrie shells, or glass beads.

The masks in Africa are usually tied to the face with bands or held there by a scarf or a wig made of raffia. Some have a horizontal peg inside for the dancer to hold between their teeth. Costumes can be made with palm leafs or various local fabrics or leather. Some have used bark cloth, but not to the degree that Oceanic masks have.

West Africa, and in particular modern Nigeria, provides the longest surviving tradition of African terracotta sculpture . They date back two and a half millennia to the extraordinary Nok sculptures. The people of the Nok culture occupied the Bauchi plateau of central Nigeria from approximately 1000 BC to 500 AD. They were innovative iron smelters, but the Nok culture is best known today for its Nok and associated Katsina and Sokoto terracotta figures. They portray both animals and humans in various postures. The human figures often have elaborate hair, modeled jewellery, and sometimes portray physical ailments. Because the vast majority of Nok terracottas have been looted from their archaeological contexts, their function in Nok society is unknown.

The Nok statuettes are mainly of human subjects. Made of terracotta, they combine strong formal elements with a complete disregard for precise anatomy. Their expressive quality places them unmistakably at the start of the African sculptural tradition. By around the 1st century figures of a wonderful severity are being modeled in the Sokoto region of northwest Nigeria.

Terracotta heads and figures have been found in Ife, dating from the 12th to 15th century - the same period as the first cast-metal sculptures of this region. The so-called Djenné statuary emerged circa A.D. 700 and flourished until 1750. The terracotta statues were manufactured by various groups inhabiting the Inland Niger Delta region of present-day Mali, centered around the ancient urban center of Djenné-Jeno. These terracotta sculptures express a remarkable range of physical conditions and human emotions, providing the largest corpus of ancient sacred gestures of any civilization in Sub-Saharan Africa.

One extraordinary group of terracottas is the exception in this mainly west African story, in that they come from south Africa where they are the earliest known sculptures. The Lydenburg heads are one of the earliest known forms of African sculpture in Southern Africa and are dated at between AD500 and AD800. There are seven hollow terracotta sculptures which are named after the site at which they were discovered in the late 1950s. Replicas of the seven terracotta 'Lydenburg heads' found in the valley of the Sterkspruit and dating to the 5th century are to be found at the local museum. Six of the heads are human and the seventh is some kind of animal replica. It is believed that they were used as ceremonial objects during the performance of initiation ritual

Powerful terracotta figures in traditional style continue to be made in Africa in the 19th and 20th century, contemporary with the superb carved wooden figures which survive from those two centuries.

Madonna and Child, an Ethiopian masterpiece of African art from an illuminated Amharic manuscript. The compositional balance of the design along with the stylistic definition of faces are stunningly expressive and elegant It contained elements of fluidity and symmetry, that are conventional representations sufficiently suggestive to convey the intended images to the mind, without destroying the unity of the theme.

Abraham and Isaac, an illuminated Amharic manuscript

“The masks weren’t like other kinds of sculpture. Not at all. They were magical things. And why weren’t the Egyptian pieces or the Chaldean? We hadn’t realized it: those were primitive, not magical things. The Negroes’ sculptures were intercessors… Against everything, against the unknown, threatening spirits. I kept looking at the fetishes. I understood; I too am against everything. I too think that everything is unknown, is the enemy! I understood what the purpose of the sculpture was for the Negroes. Why sculpt like that and not some other way? After all, they weren’t Cubists! Since Cubism didn’t exist… all the fetishes were used for the same thing. They were weapons. To help people stop being dominated by spirits, to become independent. Tools. If we give form to the spirits, we become independent of them. The spirits, the unconscious, emotion, it’s the same thing. I understood why I was a painter… Les Demoiselles d’Avignon must have come to me that day – not at all because of the forms, but because it was my first canvas of exorcism – yes, absolutely!” Picasso as quoted by André Malraux, in La Tête obsidienne (Paris: Gallimard, 1974; pp. 17–19)The African face masks are for the most part very characterful and vibrant. They are usually made of wood, and are used to cover the face or the head. Many of them are decorated with rhythmical geometric patterns. These artistic masks depict varied expressions and project different pathos. They may suggest a brutish or belligerent look; or a jubilant or amusing expression, and at times convey an air of wisdom and solemnity. Some are part of a traditional costume of festivities, and have been created for specific purpose. Some are created to spell demonic spirits, while others are used to attract favors from the benevolent forces of the universe. The sage Ogotemmeli, the first Sudanese to explicate the meanings of the African culture, has said;

The society of masked men is the whole world. And when it moves in the public square, it mimes the movement of the world, it mimes the system of the world.To understand the intricacy of these masks' meaning, as Marcel Griaule has argued; they should be studied in the context of their rituals, where "the hole corps de ballet sheds light on the order of the world. The rhythms of the drums are the actual rhythms of the creation 'danced' by the demiurge".

The highly artistic Yaka people reside in Kwango River area in the southwest of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Yaka carve numerous masks and headgears for use in initiation ceremonies (n-Khanda) and to be worn by traditional leaders.Oral history suggests that the Yaka, along with the Suku, were part of an invasion against the Kongo Kingdom that came from the Lunda Plateau in the 16th century. Among the Yaka, the males contribute to the local economy largely through hunting. They may hunt either individually or in groups and most often use bow and arrow or old rifles. The Yaka follow matriarchal descent patterns, which are overlapped with a reckoning of patriarchal ascent, family name, and land ownership. In their system of belief, the creator who inhabits the sky (ndzambyaphuungu) is responsible for life, death, and all metaphysical questions. They follow no specific religious practices that actively pay homage to this god. Instead, religious celebrations focus on honoring the elders and ancestors (bambuta). The death of an elder is cause for a public ceremony performed by other elders. Bambuta may be honored by recognizing and practicing the traditional ways and through offerings and gifts.

The initiation ceremony is organized every time there are enough eligible youths between ten and fifteen years of age. A special hut is built in the forest to give shelter to the aspirants during their retreat; the event ends in circumcision, an occasion for great masked festivities including dances and songs. The main feature of these masks are their remarkable personal characters . The above mask is of the popular kholuka form, featuring globular or tubular eyes, a turned-up nose, and an open mouth showing its teeth.

The initiation ceremony is organized every time there are enough eligible youths between ten and fifteen years of age. A special hut is built in the forest to give shelter to the aspirants during their retreat; the event ends in circumcision, an occasion for great masked festivities including dances and songs. The main feature of these masks are their remarkable personal characters . The above mask is of the popular kholuka form, featuring globular or tubular eyes, a turned-up nose, and an open mouth showing its teeth.

There are more than 60 ethnic groups in Cote D'Ivore, the main ones are the Baoulé in the center, the Agri in the east, the Senufo in the north, the Dioula in the northwest and west, the Bété in the center-west and the Dan-Yacouba in the west. Each one of these groups have their own distinct art. It is said that no one produces a wider variety of masks than the people of the Ivory Coast. Masks are used to represent the souls of deceased people, lesser dieties, or even caricatures of animals. The ownership of masks is restricted to certain powerful individuals or to families. This Baoulé mask is part of ‘portrait masks’ of men and women, Kpan Pre, Kpan Kpan. The masks usually portray a distinguished elder of the village who is celebrated during a ceremonial dance known as “Mblo”. Mblo is an artistic performance in which the guests wear exquisitely carved masks along with a colorful costumes and participate in a ritual dance. The dance celebrates feminine virtues including graceful movements and elegant dancing steps. One of Côte d'Ivoire's most famous festivals is the Fêtes des Masques (Festival of Masks), which takes place in the region of Man occurs in November. Numerous small villages in the region hold contests to determine the best dancers and to pay homage to forest spirits who are embodied in the elaborate masks.

The other important events are the week long carnival in Bouaké each March, and the Fête du Dipri in Gomon, near Abidjan in April. The starts around midnight, when women and children sneak out of their huts and, naked, carry out nocturnal rites to exorcise the village of evil spells. Before sunrise the chief appears, drums pound and villagers go into trances. The frenzy continues until late afternoon of the next day. Only specifically designated, specially trained individuals are permitted to wear the masks. It is believed dangerous for others to wear ceremonial masks because each mask has a soul, or life force, and when a person's face comes in contact with the inside of the mask that person is transformed into the entity the mask represents.

|

| Carved Mother and Twins, Anyi Tribe, 1940. |

The Anyi tribe is part of the Akan residing in the Southern portion of the Ivory Coast. Twins have always been prized among the tribes of West Africa. This figure is of a mother on stool with twins sitting on her knees each holding a breast. It has some encrustation and the neck has rings of white pigmentation. More than likely this was symbolic of fertility.

|

| Maiden-spirit mask, Eastern Ibo - Igbo (Nigeria). |

Igbo are known for masquerades associated with the Iko Okochi harvest festival, in which the forms of the masks are determined by tradition. The festival theme varies each year. The Igbo use thousands of masks, which incarnate unspecified spirits or the dead, forming a vast community of souls.The masks are made of wood and fabric. The remarkable characteristic of these masks is that they are painted chalk white, the color of the spirit. Masked dancers wore extremely elaborate costumes (sometimes ornamented with mirrors) and often their feet and hands were covered. With their masks, the Igbo oppose beauty to bestiality, the feminine to the masculine, black to white. The masks, of wood or fabric, are employed in a variety of dramas: social satires, sacred rituals for ancestors or invocation of the gods, initiation, and public festivals. The white maiden masks, danced by men, have several layers of meanings encompassing spirit characters of different ages. The masks of the eldest daughter and her younger sisters, are characterized distinctively and are decorated with elaborate crested hairstyles. They all have small pointed breasts and wear bright polychrome appliqué cloth "body suits" whose patterning loosely resemble monochromatic designs painted on youthful females in the area. Other characters in the drama are a mother, a father, sometimes an irresponsible son, and a suitor costumed as a titled elder, whose amorous, often bawdy advances to one or more "girls" are invariably rebuffed.

Among the Igbo peoples it is believed that once a person died communication from the spirit world was possible through funerary masks worn by members of a secret society at the funeral. These individuals are responsible for ensuring that the spirit of the deceased found its way to the spirit world and did not remain in the village to cause trouble. The bright color masks suggest that they are from the South, whereas in the North the masks typically are painted white. Each year during the peak of the rainy season Ibo village groups in the southwestern region stop everyday activities for a full month. This season is dedicated to Owu, the time when water spirits descend to earth from their homes in the clouds in order to dwell and cavort among human beings. These legendary spirits materialize in villages as masqueraders. Two main opponent groups of dramatic spirit characters dance and strut and flog people in the villages most days of the month — hence the cessation of ordinary life.

Among the Igbo peoples it is believed that once a person died communication from the spirit world was possible through funerary masks worn by members of a secret society at the funeral. These individuals are responsible for ensuring that the spirit of the deceased found its way to the spirit world and did not remain in the village to cause trouble. The bright color masks suggest that they are from the South, whereas in the North the masks typically are painted white. Each year during the peak of the rainy season Ibo village groups in the southwestern region stop everyday activities for a full month. This season is dedicated to Owu, the time when water spirits descend to earth from their homes in the clouds in order to dwell and cavort among human beings. These legendary spirits materialize in villages as masqueraders. Two main opponent groups of dramatic spirit characters dance and strut and flog people in the villages most days of the month — hence the cessation of ordinary life.

|

| Igbo Male Figure |

The use of bold graphic design with its broad and vibrant application of color that reinforces the strength of the carving are striking features of this African artifact. Among the Igbo such figures are sculpted by men and painted by women. This male figure probably represented a community's founding ancestor or a warrior and was one of a large number of monumental figures kept in the men's meetinghouse to guard the private areas from intrusion. It likely was part of a group that included the founding ancestor's wife and other members of the village, such as warriors and hunters. This is one of only two published terracotta Oshugbo figures; others are copper alloy. (National Museum of African Art)

This is a Tsogo people mask, which inhabit the Ogowe River region of Gabon. It is dated between the late 19th to early 20th century. The striking disconnect between the divisions of the painted surface of this mask and the underlying carved form is a remarkable aspect of African graphic design that fascinated many Western researchers. When this mask was first exhibited in the 1950s in France, it was wrongly attributed to a different part of Africa. Later research found out that it belongs to the Tsogo peoples. It represents a wider regional tradition of facial divided color surfaces. An American writer who visited a Tsogo village in the 1860s was most impressed by the decorative designs on the doors of many of the houses and commented on the red, white and black patterns of their complicated graphic designs . (National Museum of African Art)

A Gallery of African Masks

The African rock paintings suggest that masks have been used for at least 4,000 years, and yet it is possible that masks of animal heads were used by Paleolithic man at least 35,000 years ago. Nevertheless, the oldest African artifact that is definitely a mask is the highly realistic copper mask of the oni (leader) Obalufon, from the Ife kingdom of Nigeria (12th to 15th century). The eyeholes and the holes in the mask for strings of beads or raffia attachments indicate that it was worn in some ceremony. Wearing their sacred masks during their festivals, African masked performers, usually dancing on stilts, enacted rituals of myth of creation, hero worship, fertility rituals, agricultural festivities, funerals or burials, ancestor cults, and initiations,

Their high priest possessed the masks and guarded them in a sacred hut. Being, in fact, spirits of the wilderness each mask were used for a number of different functions, sometimes as the agents, who intermediates between the village and the forest initiation camp, may prevent bush fires during the dry season, used in pre-war rituals , and for peace-making festivals.

In their spiritual journey to understand the unknown, African artists create the most exquisite stylized designs, with a stunning sense of balanced compositions that are usually unique, with various combinations of curved surfaces, an elongated linear nose, a protruding and sometimes geometric mouth which are often covered in a richly colored patina. The majority of these masks are wood, and mask usage is clearly tied to areas where wood is available. There are symbolic references to the kind of wood used from various trees and the dancers who may often dance in masks taller than their own heights perform their rituals with utmost conviction . The use of raffia attachments add to the aesthetics of the mask in an artistically elegant way.

The carving of the masks are mostly done with a large long-handled axe known as an adze. The African carver is able to acquire amazing accuracy with this large instrument, and even though he has double-edged knives and chisels for fine detailing, the majority of the work is handled with the adze. To some extent, the use of better technology is not welcome for something that has ritual purpose.

Various cultures specialize in different materials for their masks - Basketwork in the Congo, Bronze masks of the Senufo, or metal surfacing among the Marka. African authentic carvers have also been resourceful in the many materials they might include on the mask, like sheet metal, fur, animal teeth, cock`s feather, human hair, textile, glass, cowrie shells, or glass beads.

The masks in Africa are usually tied to the face with bands or held there by a scarf or a wig made of raffia. Some have a horizontal peg inside for the dancer to hold between their teeth. Costumes can be made with palm leafs or various local fabrics or leather. Some have used bark cloth, but not to the degree that Oceanic masks have.

West Africa, and in particular modern Nigeria, provides the longest surviving tradition of African terracotta sculpture . They date back two and a half millennia to the extraordinary Nok sculptures. The people of the Nok culture occupied the Bauchi plateau of central Nigeria from approximately 1000 BC to 500 AD. They were innovative iron smelters, but the Nok culture is best known today for its Nok and associated Katsina and Sokoto terracotta figures. They portray both animals and humans in various postures. The human figures often have elaborate hair, modeled jewellery, and sometimes portray physical ailments. Because the vast majority of Nok terracottas have been looted from their archaeological contexts, their function in Nok society is unknown.

The Nok statuettes are mainly of human subjects. Made of terracotta, they combine strong formal elements with a complete disregard for precise anatomy. Their expressive quality places them unmistakably at the start of the African sculptural tradition. By around the 1st century figures of a wonderful severity are being modeled in the Sokoto region of northwest Nigeria.

Terracotta heads and figures have been found in Ife, dating from the 12th to 15th century - the same period as the first cast-metal sculptures of this region. The so-called Djenné statuary emerged circa A.D. 700 and flourished until 1750. The terracotta statues were manufactured by various groups inhabiting the Inland Niger Delta region of present-day Mali, centered around the ancient urban center of Djenné-Jeno. These terracotta sculptures express a remarkable range of physical conditions and human emotions, providing the largest corpus of ancient sacred gestures of any civilization in Sub-Saharan Africa.

One extraordinary group of terracottas is the exception in this mainly west African story, in that they come from south Africa where they are the earliest known sculptures. The Lydenburg heads are one of the earliest known forms of African sculpture in Southern Africa and are dated at between AD500 and AD800. There are seven hollow terracotta sculptures which are named after the site at which they were discovered in the late 1950s. Replicas of the seven terracotta 'Lydenburg heads' found in the valley of the Sterkspruit and dating to the 5th century are to be found at the local museum. Six of the heads are human and the seventh is some kind of animal replica. It is believed that they were used as ceremonial objects during the performance of initiation ritual

Powerful terracotta figures in traditional style continue to be made in Africa in the 19th and 20th century, contemporary with the superb carved wooden figures which survive from those two centuries.

The bronze head of Olokun, (divine king or Oni) founder of the Yoruba Dynasty. British Museum. The strong realism of this and other magnificent Ife sculptures is in sharp contrast to the usual abstract forms of African art. Ancient Ile-Ife situated at southwest of Nigeria was a splendid walled city covering a considerable area and at its heart was the royal palace. The city had a network of sacred shrines, planned complexes of buildings, streets, courtyards, and patterned potsherd and stone paved roads. In Yoruba mythology the city of Ile-Ife is “the navel of the world,” the place where creation took place and the tradition of kingship began.

T here it was that the gods Oduduwa and Obatala descended from the heaven to create earth and its inhabitants. Oduduwa himself became the first ruler, oni, of Ile-Ife. To this day Yoruba kings trace ancestry to Oduduwa. Of all the centers of African art, there is none so remarkable for extraordinary accomplishments in many fields of art as the ancient town of Ife, the ritual center of the great Yoruba tribe of western Nigeria.

The art of Ile-Ife flourished from about A.D. 800 to 1600 and exhibited great technical excellence and artistic refinement. Between the eleventh and fifteenth century the artists of Ile-Ife developed a highly naturalistic sculptural tradition in terra-cotta or pottery sculpture. Later, this was translated into bronze and brass castings using alloys of copper and zinc. Bronze portrait heads and figures were produced to commemorate deceased kings and chiefs.

T here it was that the gods Oduduwa and Obatala descended from the heaven to create earth and its inhabitants. Oduduwa himself became the first ruler, oni, of Ile-Ife. To this day Yoruba kings trace ancestry to Oduduwa. Of all the centers of African art, there is none so remarkable for extraordinary accomplishments in many fields of art as the ancient town of Ife, the ritual center of the great Yoruba tribe of western Nigeria.

The art of Ile-Ife flourished from about A.D. 800 to 1600 and exhibited great technical excellence and artistic refinement. Between the eleventh and fifteenth century the artists of Ile-Ife developed a highly naturalistic sculptural tradition in terra-cotta or pottery sculpture. Later, this was translated into bronze and brass castings using alloys of copper and zinc. Bronze portrait heads and figures were produced to commemorate deceased kings and chiefs.

Ife Wooden Divination Tray, Areogun of Osi-Ilorin, Nigeria; Yoruba People, about 1880 - 1956.This is a fine example of African graphic design. The tray depicts some of the most important fortunes, that are at the heart of Yoruba philosophy: a healthy long life, wealth, love, children, wisdom and security. All these good fortunes are conveyed by the graphic designer of this tray .Eshu, the god who mediates between the world of the spirit and the human world symbolizes a healthy long life and is carved at the top of this tray. At the bottom, a kneeling woman with a child on her back, presenting offerings in a calabash represents children and fertility. In the left, a soldier stands in guard with a crossbow, he is a symbol of security or victory over the enemies. In the right, a priest of Osanyin, a god of healing and wisdom is depicted. He represents the health, and wisdom . At the lower left, love is represented by a couple making love, and at the lower right, a seated figure, probably a second representation of Eshu closes this circle of life . Representing wealth, a band of cowry shells, formerly used as money in West Africa, runs around the central part of the tray.The diviner sits with the tray in front of him, placed so that Eshu is opposite, facing him.

Benin Head, A bronze sculpture from the Kingdom of Benin. The Benin kingdom was a thriving empire situated in present-day Nigeria. Accruing its economic wealth through commerce with countries north of the Sahara, Benin rose during the 16th century and became the dominant military power and imperial force on the West Coast of Africa. At its political and religious center was a fortified city surrounded by a wall almost ten feet high. The king, or oba , of Benin, was both a political and a religious leader, and believed to be divine. Iconic works of this kind are among the masterpieces of the arts of Africa. To exalt Oba and his lineage, artists created a vast variety of cast-metal objects in the technically challenging ciré perdue technique.

Benin Head of a queen mother wearing a headdress and collar of coral bead. Cast bronze. The ancient Benin kingdom was founded in the early 14th century. The Benin resided in the forest area of southwestern Nigeria. The art of lost wax bronze casting was introduced around the year 1280 and reached its peak in the 15th and 16th centuries. Fabulous bronze castings from this period and later have resided in the museums of Europe since the late 19th century.

According to the legends, when the first Oba of Benin died his head was sent to Ife for burial. Ife sent back a bronze replica of his head to be placed in the ancestors altar. Fascinated by this artifact the royal house of Benin beseeched the Ife king to send them an artist in order to teach the Benin artisans how to cast in bronze. The Ife king oliged the request and sent the renowned artist Ighea who thought them the ciré perdue technique.

According to the legends, when the first Oba of Benin died his head was sent to Ife for burial. Ife sent back a bronze replica of his head to be placed in the ancestors altar. Fascinated by this artifact the royal house of Benin beseeched the Ife king to send them an artist in order to teach the Benin artisans how to cast in bronze. The Ife king oliged the request and sent the renowned artist Ighea who thought them the ciré perdue technique.

Madonna and Child, an Ethiopian masterpiece of African art from an illuminated Amharic manuscript. The compositional balance of the design along with the stylistic definition of faces are stunningly expressive and elegant It contained elements of fluidity and symmetry, that are conventional representations sufficiently suggestive to convey the intended images to the mind, without destroying the unity of the theme.

Abraham and Isaac, an illuminated Amharic manuscript

This detail from an Ethiopian painting with its line drawing, and coloring scheme anticipates many of the techniques used in modern posters. (end of 17th century). The painting is from the northern wall of the Church of Abbas Antonios, Gondar, Ethiopia and now is in Musée des Arts Premiers, Musée du quai Branly, Paris.

Ethiopia is the oldest independent country in Sub Saharan Africa. The earliest evidence of Ethiopian history was in around 1,000BC when the Queen of Sheba visited King Solomon. The first recorded kingdom in Ethiopia grew around Axum between the 1 st and 3rd century BC. Axum was an offshoot of the Semitic Sabeam kingdoms of southern Arabia, it became the greatest ivory market in the north east. Christianity was adopted in the country by a Syrian bishop named Frumentius who grew up in Axum and converted King Ezana; the youth was later made the first Bishop in 330 AD. Ezana declared Axum to be a Christian state , thus making it the first Christian state in the history of the world, and began actively converting the population to Christianity.

An Iilluminated Ethiopian Christian manuscript on display at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art in Salem.

Axum conquered parts of Yemen and southern Arabia and remained a great power until the death of the Prophet Mohammed. Islam was expanding which had the effect of cutting off Ethiopia from its former Mediterranean trading partners and allies, Muslims replaced the Egyptians in the Red Sea ports. Ethiopians were allowed to consecrate their Bishops in Cairo and pilgrims were allowed to travel to Jerusalem.

Archangel Raphael, Ethiopian, 20th century, tempera on parchment, collection of Father David Janes, Yamhill, Oregon, Photo: Frank Miller

Featured in the exhibition: Glory of Kings: Ethiopian Christian Art from Oregon Collections

Ethiopia is the oldest independent country in Sub Saharan Africa. The earliest evidence of Ethiopian history was in around 1,000BC when the Queen of Sheba visited King Solomon. The first recorded kingdom in Ethiopia grew around Axum between the 1 st and 3rd century BC. Axum was an offshoot of the Semitic Sabeam kingdoms of southern Arabia, it became the greatest ivory market in the north east. Christianity was adopted in the country by a Syrian bishop named Frumentius who grew up in Axum and converted King Ezana; the youth was later made the first Bishop in 330 AD. Ezana declared Axum to be a Christian state , thus making it the first Christian state in the history of the world, and began actively converting the population to Christianity.

An Iilluminated Ethiopian Christian manuscript on display at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art in Salem.

Axum conquered parts of Yemen and southern Arabia and remained a great power until the death of the Prophet Mohammed. Islam was expanding which had the effect of cutting off Ethiopia from its former Mediterranean trading partners and allies, Muslims replaced the Egyptians in the Red Sea ports. Ethiopians were allowed to consecrate their Bishops in Cairo and pilgrims were allowed to travel to Jerusalem.

Archangel Raphael, Ethiopian, 20th century, tempera on parchment, collection of Father David Janes, Yamhill, Oregon, Photo: Frank Miller

Featured in the exhibition: Glory of Kings: Ethiopian Christian Art from Oregon Collections

Handbuilt pottery made by women, including those from the Kabyle, an older, probably indigenous tradition, dates back 2000 years before the birth of Christ. The vessel depicted here originates from earlier prototypes. To this day, Kabyle women coil and decorate pottery with painted geometric designs for their own household use and for sale. The inhabitants of the mountainous Kabyle region along the Mediterranean coast in northeastern Algeria were superb artists noted for their jewelry making, textiles, mats, basketry, pottery and house mural decoration. In North Africa, wheel-thrown pottery made by men dates from the 7th century B.C. when the Phoenicians introduced the potter's wheel to the Algerian coast. Kabyle women handmade vessels of various sizes and shapes for holding water, milk, oil, cooking and eating food, and oil lamps.

The Bamelike is the largest of the ethnic groups inhabiting the grasslands of Cameroon. The ancient kingdoms of the Cameroon Grasslands are famous for their splendid artworks – thrones ornamented with precious beads, wooden figures sculptured by unknown masters, enormous drums, finely carved jewelery made from ivory and brass, as well as fabulous masks. These unusual broze, leather, and rafia headdresses would have been used during rituals of planting and harvesting.

Nubia is a loosely defined region of southern Egypt and northern Sudan which used to stretch more or less 800 kilometers from Aswan to the Forth Cataract on the Nile in Sudan but now extends from south of Luxor to Khartoum, Sudan. In Pharonic times, Nubia was known as the ancient kingdom of Kush. Beginning in the Middle Kingdom the ancient Egyptians obtained gold from Nubia. Gold was called nub in ancient Egypt and may be the source of the name Nubia. Ebony, ivory, leopard skins and incenses also came from Nubia or at least were transported through it from sub-Saharan Africa.

A Nubian Princess in her ox-chariot, from the Egyptian tomb of Huy, 1320 BC

A Meriotic period (250 BC - AD 350) pot. The shape of this pot is typically and distinctively Nubian with its large round shape, the lack of a base, and its short narrow neck. These pots are also typically a burnished orange color that was a result of the pot being fired and then polished. The lively images of animals, including snakes, frogs, and rabbits are another feature of the pottery from this era. The animals symbolize various aspects of life such as fertility, health and immortality,

The Egyptian God Amun also became the state god of the later Nubian kingdoms of the Sudan. This amulet is made of silver and overlain with gold. According to Egyptian mythology, the bones of the gods were silver and the flesh was gold. Its distinctive features, the long kilt and broad hips, and the image of the sun on the horizon, mark it as a Nubian, rather than Egyptian piece.

Ancient Nubian painting resembles Egyptian painting but that does not mean all of their art was derivative. Meroitic art was especially idiosyncratic and full of playfulness.Emily Teeter of the Oriental Institute told Smithsonian, "It became a very spontaneous art, full of free-flowing improvisation."

... In Short Africa Means Graphic Design!

Go to the next chapter; Chapter 16 - Minimalism

Nubia is a loosely defined region of southern Egypt and northern Sudan which used to stretch more or less 800 kilometers from Aswan to the Forth Cataract on the Nile in Sudan but now extends from south of Luxor to Khartoum, Sudan. In Pharonic times, Nubia was known as the ancient kingdom of Kush. Beginning in the Middle Kingdom the ancient Egyptians obtained gold from Nubia. Gold was called nub in ancient Egypt and may be the source of the name Nubia. Ebony, ivory, leopard skins and incenses also came from Nubia or at least were transported through it from sub-Saharan Africa.

A Nubian Princess in her ox-chariot, from the Egyptian tomb of Huy, 1320 BC

A Meriotic period (250 BC - AD 350) pot. The shape of this pot is typically and distinctively Nubian with its large round shape, the lack of a base, and its short narrow neck. These pots are also typically a burnished orange color that was a result of the pot being fired and then polished. The lively images of animals, including snakes, frogs, and rabbits are another feature of the pottery from this era. The animals symbolize various aspects of life such as fertility, health and immortality,

The Egyptian God Amun also became the state god of the later Nubian kingdoms of the Sudan. This amulet is made of silver and overlain with gold. According to Egyptian mythology, the bones of the gods were silver and the flesh was gold. Its distinctive features, the long kilt and broad hips, and the image of the sun on the horizon, mark it as a Nubian, rather than Egyptian piece.

Ancient Nubian painting resembles Egyptian painting but that does not mean all of their art was derivative. Meroitic art was especially idiosyncratic and full of playfulness.Emily Teeter of the Oriental Institute told Smithsonian, "It became a very spontaneous art, full of free-flowing improvisation."

... In Short Africa Means Graphic Design!

Go to the next chapter; Chapter 16 - Minimalism

References

- Augé, Gillon, Hollier Larousse Moreau et Cie, L'Art et L'homme, Librarie Larousse , Paris, 1957.

- Susan Mullin Vogel, Baule: ''African Art, Western Eyes'', Yale University Press (October 20, 1997), ISBN 0300073178, ISBN 978-0300073171, Peter Stepan, Prestel Publishing (October 31, 2005), ISBN 3791332287, ISBN 978-3791332284

- Andreae, Christopher. "African Art: Its Beauty, Form, and Function." Christian Science Monitor IS Apr. 1996, SIRS Inc.

- J. D. Fage, J. Desmond Clark, The Cambridge history of Africa: From the earliest times to c. 500 BC,Cambridge University Press, 1982, ISBN 052122215X,

- Werner Gillon, A Short History of African Art, Penguin (Non-Classics), 1991, ISBN-10: 0140136118

- Jean-Baptiste Bacquart, The Tribal Arts of Africa, Thames & Hudson ,2002 , ISBN-10: 0500282315

- Ezio Bassani, Arts of Africa: 7000 Years of African Art, Skira, 2005, ISBN-10: 8876242848

- Monica Blackmun Visona, Robin Poynor, Herbert M. Cole, and Preston Biler History of Art in Africa, Prentice Hall; 2 edition, 2007, ISBN-10: 0136128726

It is very helpful. Thank you for this wonderful service you provide to us.

ReplyDeleteBut I have a question that I think hopeful you will assist us. I want to know "How African Art viewed on Western Eyes''

Authentic art can always be approached from various cultural sensitivities, and can always communicate with other great artistic traditions. For instance, the outstanding artistic achievements of Baule artists from Cote d'Ivoire in West Africa can be appreciated from the perspective of Greek sculpture, which from Herodotus we learn that images were also magical. If a Spartan king died abroad, an image was made and placed on a decorated bier and carried to the grave at Sparta. The magical quality of art, like its African counterpart is illustrated by the action of Phocaeans who, fleeing from the city before the Persians, took with them the images of their gods. Herodotus says specifically that the paintings, stone and bronze objects were left behind. He does not discuss how Greeks viewed the Greek art, its content, style, and artistic personality, but describes expense, materials and clever workmanship. Such an attitude is in a way, universal, shared by the unsophisticated of our own day. Nevertheless, as R. Ross Holloway argues:

ReplyDelete" In fact for archaic Greece and for a significant element of classical Greece art was truly what the Greek work techne implies, craft. It was appreciated for the dexterity of its makers, its complexity and material splendor. Good design, harmony and balance were appreciated. The presences evoked by art, whether divinities or heroes, were magical with all the connotations of that word, and although the themes of narrative art were not chosen randomly, it was the combination of awe before the magical image, and naive response to vitality and action that gave early Greek art its power. "

In a similar vein for African art as Susan Mullin Vogel’s Baule: African Art, Western Eyes (Yale University Press), describes:

“Although Baule art is important in the Western view of African art, the people who made and used these objects do not conceive them as ’art,’ and may equate even the finest sculptures with mundane things, devoid of any visual interest, that have the same function and meaning.... ’Art’ in our sense does not exist in Baule villages, or if it does villagers might point to modern house decorations, rather than famous traditional sculptures still made and used in villages and evoked by the term ’African art.’”

THANK YOU FOR ALL INFORMATIONS!!!! YOUR WORK IS VERY PRECIOUS!!!!!

ReplyDeleteBe blessed

ReplyDelete