|

The double-winged farohar motif surrounded by six Amesha Spentas (archangels). Achaemenid era Persian earring. Gold with cloisonné style inlays of turquoise, carnelian, and lapis

lazuli. Diameter: 5.1 cm . Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

|

Jewelry has been a form of visual communication from the start of human history, and from the beginning it has always assumed a form of personal adornment while it projected a type of status symbol up to the position of kings and emperors. It is likely that from an early date Jewelry was also worn as a protection from the dangers of life, and as a conduit for dealing with mystical aspects of culture. Jewelry made from shells, stone and bones has survived from prehistoric times. In the ancient world the discovery of how to work metals was an important stage in the development of the art of jewelry. Over time, metalworking techniques became more sophisticated and decoration more intricate. In many cultures, as we shall see, jewelry was frequently included in burials and at times was offered to various temples by believers. The contextual information uncovered through excavations provides important clues about beliefs, customs, cultures, relationships, and the use of jewelry as talismans. Of course, one has to be extremely careful in these types of analysis, as Megan Cifarelli(2009) has argued at times various exhibitions provide misleading information. For example, in the absence of detailed contextual information for the following Mesopotamian necklace an exhibition text was focusing on"the use of materials such as gold, silver, lapis lazuli, carnelian, shell, and agate" Cifarelli argues:

As the exhibition text indicates, none of these materials was available locally, suggesting that they were valued not just for their beauty but because they were difficult to obtain. Gold, lapis lazuli, and carnel;ian were imported as raw materials: gold from Anatolia, Iran, and Egypt; carnelian from Iran and Indus Valley; lapis from the Badakhshan region of what is now Afghanistan. Two types of carnelian beads, those etched with alkali and long, biconical tubes, were likely crafted at Indus Valley Sites (...) Excavators have often published finds of beads as reconstructed "nrcklace" without articulating any rationale for the reconstructions, and these hpothetical reconstructions are perpetuated by scholars and museum displays. One such 'necklace is highlighted in the Mesopotamia case; it is a symmetrical grouping of beads typical of the late Early Dynastic period / Akkadian era and consisting of gold tubes, lapis lazuli in biconical and globular forms, long biconical carnelian tubes, etched and plain carnelian barrels, and carnelian lentoids etched with a white ring. Despite the persistent necklace reconstruction, paralles from Mohenjo Daro and possibly Ur suggest that these weighty carnelian tubes were used for hip and waist gridles rather than necklace.

.

|

Mesopotamian carnelian, lapis lazuli, and gold beads, restored as a necklace, mid third millennium BC from Irak, Kish. Chicago, The Field Museum of Natural History. |

|

| Native American Indian ring |

|

Native Indian American jewelry |

|

African beads, jewelry and crafts |

|

African bridal jewellery |

.

|

| African Collar |

Much archaeological jewelry

comes from tombs and hoards. The best-known ornaments in early

Neolithic graves in central Europe are those of the marine spondylus

shell, imported from the Aegean, or to a lesser extent from the Adriatic

coast. These ornaments are clearly connected to the richest burials and

must have been of extremely high value. They are the most important

evidence of long-distance connections through Europe in early to middle

Neolithic times (Séfériades 1995; Müller 1997; Kalicz and Szénászky

2001).

|

Elite gold jewelry in the La Tène style from a 'chieftain's' grave at Waldalgesheim, in the Rhineland, Germany

|

Today, the Akan tradition in

Ghana in Africa still believes in life after death – Saman Adzi, where

one continues life in relative luxury to when living. This is why

families bury their dead with basic items like clothing, jewellery,

hankies and money for the journey into the next world. Other burial

items differ from family to family. As early as the 15th century,

European merchants wrote about the richness of African gold objects used

for adornment and intended for public display. Gold deposits were

discovered in all regions of Africa, and became the most important

commodity during pre- colonial times. The region of the Akan, spreading

from the forest zone and costal areas of Ghana to the southern shores of

the Ivory Coast, is the richest auriferous zone in West Africa. Several

individual tribes make up the Akan people, the Asante and Baule being

among the most famous, all united by their common ancestry and language.

The royal courts of the Akan people were reportedly the most splendid

in Africa. Oral tradition and iconography in Akan works of art are very

closely connected. Verbal and visual symbolism tells stories or

proverbs. Imagery of royal power on court ornaments carry out messages

that helps keep the balance and continuity within the society.

|

Akan Gold Bead Necklace |

|

18th century African Beaded Necklaces |

Burying valuable objects with the dead has

also been a practice in China and other Asian countries for several

thousand years. In addition to gold, silver and other valuables, burial

objects include daily necessities, arts and crafts, the four treasures

of study (writing brush, ink stick, ink slab and paper), books and

paintings, tools of production and scientific and technological devices,

and these have turned many tombs into priceless underground treasure

houses, telling the vogues of the times. At the Cambodian sites of Vat

Komnou/Angkor Borei (Takeo province) and Village (Kampong Cham

province) about 100 burials of the 4th century BC to the 2nd century AD

with many offerings have been discovered.

Further, about 50 burials

excavated at Go O Chua in Long An province in southern Vietnam provide

additional information from the late phase of the Pre-Angkor period.

With its unusually rich offerings, the burial site of Prohear surpasses

all expectations. The burial sites of this region show clear cultural

similarities (e.g. high pedestalled bowls of the same shape and

ornamentation), but also display strikingly distinctive local features.

Thus, the wealth of gold offerings is without comparison at any other

burial site of the early Iron Age period in this region and the great

number of bronze drums from the site - although mostly undocumented - is

hitherto unique for the southern parts of mainland Southeast Asia, far

away from the Dong Son cultural area.

|

Gold jewelry from different Cambodian burials |

In 2003, an archaeological expedition dug up a burial

mound in the Shiliktinskaya Valley to find a Golden Man – a presumed

leader of the Saka tribe, a branch of the Scythian nomads that populated

Central Asia

and southern Siberia in the 1st millennium BC. The pagan Saka fought the

ancient Persians, and grew rich

through trading across the great steppes of Central Asia. Some of their

wealth ended up in the tombs of their chieftains, who were buried

wearing jewelry and gold-plated armor – like the man in the

Shiliktinskaya mound, the third such find in Kazakhstan since 1970.

|

Jewelry found in the burial mound of the first “Golden Man” in 1970 |

The Bronze Age civilization

that flourished on the Mediterranean island of Crete is known as the

Minoan. Because Crete lay near the coasts of Asia, Africa, and the Greek

continent and because it was the seat of prosperous ancient

civilizations and a necessary point of passage along important

sea-trading routes, the Minoan civilization developed a level of wealth

which, beginning about 2000 bce, stimulated intense goldworking

activities of high aesthetic value. From Crete this art spread out to

the Cyclades, Peloponnesus, Mycenae, and other Greek island and mainland

centres. Stimulated by Minoan influence, Mycenaean art flourished from

the 16th to the 14th century. Middle Minoan period, in Greece, when

rapid social changes took place, with palaces emerging for the first

time, but also being destroyed and having to be rebuilt. The Minoan

society was changing rapidly and the people associated with the palaces

needed consensus from the larger population, to affirm their social

ranking and maintain control.

The emerging social tensions increased the power of religion as a stabilizing force for maintaining the social structural of order. The

recurring iconography of a Minoan goddess descending on a throne seems

to became a key symbol of the legitimization of the new social

order. In the Bronze Age, Mycenaean people had strong spiritual beliefs

about an afterlife and the fact that we are seeing bodies that have been

embalmed and items buried with them, gives evidence for this. They

believed that once you die, your body needs to be respectably buried for

it to be able to move on and that you also needed objects from the

material world to take up with you in the after life. This was not only

for use in the afterlife, but they thought that to get to the afterlife,

you had to cross a river that charged a fare, so if you did not have

items to pay, then you would not get to

go to the next life. A profusion of gold jewelry was found in early

Minoan burials at Mókhlos and three silver dagger blades in a communal

tomb at Kumasa. Silver seals and ornaments of the same age are not

uncommon.

|

Minoan Gold bracelet, the eyes and eyebrows were originally inlaid. |

The

first evidence of jewelry making in Ancient Egypt dates back to the 4th

millennia BC, to the Predynastic Period of along the Nile River Delta

in 3100 BC, and the earlier Badarian culture (named after the El-Badari

region near Asyut) which inhabited Upper Egypt between 4500 BC and 3200

BC. From 2950 BC to the end of Pharaonic Egypt at the close of the

Greco-Roman Period in 395 AD, there were a total of thirty-one

dynasties, spanning an incredible 3,345 years!

Figure on the left shows a pectoral that hangs from a single string of cylindrical beads of blue faience and gold, a rearing

Uraeus guards, the Wadijet-eye and the hieroglyph Sa is placed beneath it on the inner side.

Figure on the right shows a pectoral scarab that contains gold, silver, cornelian, lapis lazuli, calcite, obsidian

and red, black, green, blue and white glass. The central necklace motifs consist of a bird with upward

curving wings whose body and head have been replaced by a fine scarab. It represents the sun about to

be reborn. Instead of a ball, the scarab is pushing about containing the scarab Wadijet-eye which is

dominated by a darkened moon, holding the image of Tutankhamun become a god, guided and

protected by Thoth and Horus. Heavy tassels of lotus and composite bud forms are the base of the

pendant.

Wig of gold, onyx and stained glass. 1479-1425 BC. Used by one of the wives of Thutmose III

The

earliest known record concerning the making of jewelry is found in

Egypt. It is here along the stone walls of the chapel chambers of

ancient tombs that the true history of jewelry begins. On these walls

are reproductions of the Egyptian lapidary at work. This craftsman was

essential to Egyptian jewelry for it was his job to cut and engrave the

many small stones found in almost all Egyptian work. During this time,

the jeweller was not only a skilled craftsman who made ornaments for

personal adornment, but a goldsmith and engraver of metals for any

purpose, including the minting of coins. Although the beginnings of

jewelry as we know it can be traced to this time, Egyptians also had

characteristic forms of jewelled ornaments for which we have no

equivalent. The pectoral is one of these.

|

The piece on left is a bracelet made of gold, lapis lazuli, cornelian and turquoise. The gold bangle with openwork scarab is set in lapis lazuli. At the king and the clasp are clusters composed of fruit in yellow quartz, buds in cornelian and completed with gold rosettes. The piece on right contains the materials gold, lapis lazuli, green stone and coloured glass. This pendant consists of the Eye of Hours, symbol of the entity of the body, on the right Uraeus, wearing the royal crown of the north, on the left the Vulture of the south seem to be defend and protect the

Wadijet-eye which is to help rebirth

|

Ancient

Egyptians began making their jewelry during the Badari and Naqada eras

from simple natural materials; for example, plant branches, shells,

beads, solid stones or bones. These were arranged in threads of flax or

cow hair. To give these stones some brilliance, Egyptians began painting

them with glass substances. Since the era of the First Dynasty, ancient

Egyptians were skilled in making jewelry from solid semiprecious stones

and different metals such as gold and silver. The art of goldsmithing

reached its peak in the Middle Kingdom, when Egyptians mastered the

technical methods and accuracy in making pieces of jewelry. During the

New Kingdom, goldsmithing flourished in an unprecedented way because of

regular missions to the Eastern Desert and Nubia to extract metals.

These substances were processed and inlaid with all sorts of

semiprecious stones found in Egypt; for example, gold, turquoise, agate,

and silver.

|

The jewel on the left is a rebus for the throne name of

Tutankhamun, i.e. Nebkheperure, which can be translated as ‘Re is the lord of manifestation’. At the

bottom is a basket representing Neb made of turquoise. Above this is a lapis lazuli scarab beetle is the

sign for kheper, with three vertical lines below to make it plural. A cornelian sun disk is also visible,

symbolising of the sun god Re.

Figure on the right is a scarab pectoral made up of gold, cornelian, red and blue glass. This pectoral has an

exterior shape which is massively architectural. The interior decoration has as its principle motif a

stone scarab with wings. Its protection is assured by Isis and Nephthys; the words of the goddesses

and names of the king are inlaid in gold bands above the scarab. Again, the scene is dominated by the

solar disk, winged with rich feathers and accompanied by two protective Uraeus

|

The ancient Egyptians placed great

importance on the religious significance of certain sacred objects,

which was heavily reflected in their jewelry motifs. Gem carvings known

as “glyptic art” typically took the form of scarab beetles and other

anthropomorphic religious symbols. The Egyptian lapidary would use emery

fragments or flint to carve softer stones, while bow-driven rotary

tools were used on harder gems.

|

Amulet representing a ram-headed falcon. Ancient Egypt, 1254 BC (26th

year of the reign of Ramses II), found in the tomb of an Apis bull in

the Serapaeum of Memphis at Saqqara. Gold, lapis, turquoise and

cornelian.

|

|

Bracelet from the Oxus treasure, Achamenid period, British Museum. London. |

|

Gold necklace, with king and flanking lions in carved lapis lazuli; Sassanian period, 5th - 6th century A.D. |

|

Elements from a necklace, probably 14th century Iran

Gold sheet, chased and inset with turquoise, gray chalcedony, glass; large medallion |

|

A Parthian empire collar necklace from a tomb in Tillia Tepe, Afghanistan. 1st. century AD

|

|

Parthian gold jewelry discovered in graves located at Nineveh in northern Iraq. The Persian Empire collection of the British Museum.

|

|

"The Sun and Crescent Necklace" of a Mitraist Parthian King of Kings. This is one of the most rare ancient artifacts in the world with no known analogs of its kind. Parthian King. The necklace by itself represents the “Pleiades Star Cluster” A group of seven stars that were considered sacred in Persia . |

|

| Scythian Emulate |

|

Bead necklace, Achaemenid period, c. 350 BC

Acropolis, Susa, Paris, Louvre Museum

|

|

A bracelet set with roaring lion's heads, Paris, Louvre Museum

Lavishly decorated with gold, turquoise and lapis lazuli, this bracelet set with lion's heads from the Achaemenid Persian period reflects the taste of dignitaries of the empire for jewelry and luxury. This type of object features in the sculptures decorating certain monuments, notably the Archers' Frieze in the palace of Darius at Susa (522-486 BC).

This bracelet from the Achaemenid period is a smooth, solid circular bangle six millimeters thick, with a slight inward bend in the middle of the circle. Each end is tipped with a lion's head with distinct anatomical features, similar to those found on the reliefs and enameled-brick panels in the palace of Darius I at Susa, particularly the Lion passant (Louvre Museum, aod489a). The muscle structure is shown with "dots and commas." This stylization, common in Achaemenian art, and the threatening appearance of the lions are also found on a rhyton decorated with lion's heads (Teheran Museum), a sword handle (Teheran Museum) and a lion-shaped weight (Louvre Museum, sb2718). On this bracelet, the cheeks and top of each lion's head are set with turquoise and the ruff is in lapis lazuli. The eyes and muzzle were originally incrustated, and the mane is decorated in cloisonné with pieces of turquoise. On either side of the heads are alternating incrustations of lapis lazuli and turquoise.

|

|

"

This unique crown, consisting of a band of electrum 1.5 cm wide perforated to take tie-strings at the rear and mounted with rosettes and animals heads, appears to have been made in Egypt largely under Asiatic inspiration, if it is not an Asiatic import. In the Egyptian 18th Dynasty, it became the fashion to decorate the diadems of princesses and lesser queens with the figure of a gazelle's head in place of the uraeus or vulture of principal queens. This crown with its four gazelle heads may have been part of the trousseau of a foreign princess sent as a bride for one of the [Ancient Egyptian] Pharaohs according to the [international] diplomacy of the age."

|

|

Pendant representing a naked Goddess. Electrum, made by a Rhodian

workshop, ca. 630-620 BC. Found in the necropolis of Kameiros (Rhodes). |

|

Pendant, Phoenicia 600BC-500BC, Gold set with green glass, Victoria & Albert Museum, London

|

|

This piece of jewelry was one of the most beautiful antiques excavated from the Dingling, one of the w:Ming Dynasty Tombs. It was made during the w:Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) in China, by using gold, ruby, pearl and other gemstones, and of the size of an adult human's palm. It is of the shape of a Chinese character '心' (read Xin), which literally means heart. T |

|

Collar known as The Shannongrove Gorget, maker unknown, Ireland, late

Bronze Age (probably 800-700 BC). Victoria &

Albert Museum, London. |

|

Medallion with Eros, hair ornament, second half of the 3rd century BC, Hellenised Orient, Paris , Louvre Museum |

|

Kingston Down brooch, Anglo-Saxon, early seventh-century. The ‘step’ pattern recalls the centre of the St Mark carpet page in the Lindisfarne Gospels. |

|

Ancient Greek jewlry from Pontika (now Ukraina) 300 bC. It is formed in a Heracles knot. |

|

Earrings, 4th century BC, Gold, The State Hermitage Museum

These gold filigree earrings were found during excavations of a burial mound in the environs of Theodosia. This is the most remarkable example of pieces executed in the so-called 'microtechnique' by Greek goldsmiths during the 4th century BC.

|

|

The Arimaspi Fighting Griffins Calathos (headdress), Second half of the 4th century BC, Greek work, Gold, enamel,The State Hermitage Museum.

The calathos is part of the sumptuous headdress of a priestess serving the goddess of fertility, Demeter. It was found during excavations of the Bolshaya Bliznitsa burial mound on the Taman peninsula.

|

|

A gold bracelet, weighing over 1.3 pounds and found on a victim in

Pompeii, was part of a traveling exhibit displayed at the Field Museum

in Chicago, Illinois in 2005 |

|

A pair of first century earrings, from a tomb in Tillia Tepe,

Afghanistan, when they were on display at the 'Afghanistan, Rediscovered

Treasures' exhibition at Muse Guimet in 2006 in Paris, France. |

|

Gold, set with table-cut emeralds, and hung with an emerald drop from

Colombia, currently exhibited at Victoria and Albert Museum |

|

Gold and pearl earring found in the City of

David archaeological excavation below the Old City walls in East

Jerusalem, Israel, in November, 2008.

|

|

Antique Nose Ring from India, with Gold, Pearls and Jadau work. 19th century. [courtesy Wovensouls collection]

|

|

Andhra Pradesh Royal earrings 1st Century BCE |

|

A gold broach with turquoise and a pearl, from the first century, was discovered in 1978 on the archeological site of Tillia Tepe in northern

Afghanistan. |

|

First-century earrings from a tomb in Tillia Tepe, Afghanistan. Thierry Ollivier/Muse Guimet/Getty Images

|

|

Gold earring from Mycenae, Late Helladic I (16th century BC). |

|

Ancient Egyptian collar necklace |

|

Rosette, maker unknown, Tuscany, 530 BC. Victoria & Albert Museum, London. |

|

Pendant Unknown maker England 1540 - 1560 Enamelled gold, set with a hessonite garnet and a peridot, and hung with a sapphire Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

|

Ivy Wreath. Mid 4th century B.C., Dion Archaeological Museum |

|

Oak Wreath. Mid 4th century B.C., Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum |

|

Earrings decorated with a siren and sea shells , Late fifth century B.C., London, British Museum |

|

Gold snake Bracelet , Greek-Hellenistic Period, first half of the 2nd century B.C, Pforzheim, Schmuckmuseum |

|

This inlaid gold pendant from Tillya Tepe, Afghanistan, dating

from the first century AD, is heavily inlaid with different coloured

materials, including turquoise, garnet, lapis lazuli, carnelian, and

pearl, some of which are long-distance imports

|

|

Necklace with Sapphire Pendant, bow about 1660, chain and pendant probably 18-1900. Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

Breast ornament About 1620 - 1630, France (possibly) Enamelled gold, set with 208 table-cut and triangular point-cut diamonds, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

|

|

Bodice Ornament, About 1680 - 1700, Holland (possibly), Rose-cut diamonds and hessonite garnets set in gold and silver, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

|

Talisman of Charlemagne; a valuable and precious pendant from 9th Century AD, in filigreed gold, an oval sapphire cut into a cabochon, through which a relic can be seen and with 53 precious stones including pearls, garnets, amethysts and emeralds, is not just any jewel but Talisman of Charlemagne, given to him by Caliph of Baghdad Harun al-Rashid (d. 809 AD), which he always wore on his chest and with whom he wanted to be buried. In 1000 AD, Otto III (980-1002 AD), Emperor of Holy Roman Empire, had tomb opened and took possession of talisman. Then for centuries, it remained in cathedral of Aachen until in 1804, bishop donated it to Josephine Beauarnhais, wife of Napoleon I. Josephine, upon her death, left it to her daughter Ortensia who gave it to her son Napoleon III, whose wife Eugenia kept it, finally donating it to Cathedral of Reims where it is still exhibited in Tau Palace, France.

Ancient Greek Crowns

|

Bridal crown (brudkrona),

Sweden

18th or 19th century,

Silver partly gilt,

Victoria & Albert Museum, London

This small silver-gilt bridal crown has six upright openwork elements of renaissance inspiration, joined together at the top by a ring of silver-gilt wire, with applied winged angel's heads. There are numerous pendant leaves on all parts. The band at the base is decorated with pyramidal points and more winged angel heads in silver.

Throughout the world brides wear special jewellery, such as tiaras or crowns, to reflect this. In Scandinavia, bridal crowns are the most spectacular part of the wedding jewellery. Their design is based on medieval royal originals, and they are made of heavy silver, often gilded.

In Sweden all brides wore some kind of special headdress. Gilded silver crowns were worn particularly in the east of the country, but crowns made of cloth, richly decorated with ribbons, beads, and metallic lace, were also common. Swedish bridal crowns were originally full-size, but during the 18th century they became smaller, and were worn on the top of the head.

Bridal crowns were always expensive. The bride usually hired her crown, as few families were rich enough to own their own. In Sweden most were owned by the parish church. This tradition dates from the time when church weddings were not compulsory. The church provided rich crowns to encourage people to marry there.

The renaissance decoration of this crown is typical of Swedish crowns of the 18th and 19th centuries. Many of the motifs used, such as angel's heads with wings, and leaf pendants, are also found on other pieces of Swedish traditional jewellery. It was bought for £9 at the International Exhibition, London, 1872.

|

|

Enamelled gold pendant in the form of a three masted ship hung with pearls, Designed and made by Reinhold Vasters, Aachen, Germany About 1860, Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

Bracelet;

Probably made by Charles Riffault for Frederic Boucheron,

Paris, France,

About 1875,

Gold openwork with translucent and plique-à-jour enamel set with pearls and diamonds, Victoria & Albert Museum, London

This bracelet was made by the reknowned Parisian jeweller Frédéric Boucheron (1830-1902). Boucheron gathered around him a team of fine designers and craftsmen to execute his work. Charles Riffault revived the technique of translucent or unbacked cloisonne enamelling, which he patented, but granted the monopoly of the process to Boucheron. From about 1864, Riffault executed enamels in this manner for Boucheron, who exhibited them at the International Exhibition in 1867 and 1878.

|

|

Crown of Saint Wenceslas,

The St. Wenceslas Crown wrought of extremely pure gold (21 -22 carat), decorated

with precious stones and pearls - is the oldest item of the Crown Jewels. Charles IV had it made for his coronation

in 1347 and forthwith he dedicated it to the first patron saint of the country St. Wenceslas

and bequeathed it as a state crown for the coronation of future Czech kings, his successors

to the Czech throne. However, perhaps to the end of his days (1378) he continually had the Crown altered

and set with additional rare precious stones he managed to acquire. And so the crown developed

into its final contemporary image.

|

|

Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire, 10th century; in the treasury of Hofburg palace, Schatzkammer, Vienna.

The octagonal imperial crown, created in 962 for the coronation of Otto I and studded with precious stones. The imperial orb was created in the late twelfth century and the scepter in the fourteenth century.

|

|

The Danish crown

Christian IV's crown of gold, enamel, diamonds and pearls, created 1595-1596 by Dirich Fyring in Odense.

|

|

For the anointing of Christian V, a new Danish crown was made along with a throne of narwhal teeth (the unicorn's horn) and three silver lions. Made in 1670-71 by Made by Paul Kurtz in Copenhagen for King Christian V and was modeled after a crown worn by King Louis XIV of France. Prior to 1660 the crown was elective and there was no coronation in Denmark until absolutism became the style of rule. When the 1840 Constitution ended absolutism a coronation was no longer held. The Crown has since been used only for the castrum doloris (‘camp of woe’) at the death of the monarch when the crown is placed on the coffin. |

|

The crown of Louis XV consists of an embroidered satin cap

encircled by a metal band; springing from this are openwork arches

surmounted by a fleur-de-lis, Paris Louvre Museum.

Louis XV's personal crown was designed by the jeweler Claude Rondé and

executed under the supervision of the young Augustin Duflos, jeweler to

the king at the Galeries du Louvre. Shortly afterwards, in 1723, again

working for Rondé, Duflos made a crown almost identical in design and

size for King Joseph V of Portugal. In 1725, Rondé delivered another

crown to the queen, similar in composition but smaller in size.

|

|

Crown of the kings of Bavaria (gold, silver, diamonds,

imitation blue diamond, rubies, emeralds); Marie-Étienne Nitot (jeweller)and Jean-Baptiste Leblond (goldsmith), Paris 1806-07

On

1 January 1806 Elector Maximilian Joseph IV of Bavaria was proclaimed

King Maximilian Joseph I of Bavaria. Royal insignia were immediately

commissioned from craftsmen in Paris: a crown, sceptre, sword and belt,

imperial orb and seal container for the king, and a crown for the queen.

Among the artists at Napoleon's court who worked on the insignia was

the leading goldsmith of the day, Martin-Guillaume Biennais..

The insignia were duly delivered to Munich, but political events

precluded a coronation ceremony. In fact, no king of Bavaria was ever to

wear the crown in public. On occasions such as the accession of a ruler

to his throne and his lying in state the insignia were presented on

special cushions.

|

|

The imperial crown of the Habsburg dynasty, inlaid with rubies, pearls, diamonds and a large sapphire. The magnificent golden crown was created in Prague by Jan Vermeyen, a renowned goldsmith from Antwerp.

The imperial scepter and orb were created about a decade later. |

The Imperial Crown of Russia.

|

Kiani Crown of Iran was made for the coronation of Fathali Shah of Ghadjar Dinasty in 1797. |

|

Iranian Crown was designed in 1925 by Saradjoddin Djavahery, modelled after the ancient crowns of Sassanid Empire of Persia (Iran). This was after the fall of the constitutional monarchy of Ghadjar dynasty in the first modern era military coup instigated by British. |

|

This necklace and earrings were originally part of a parure which Napoleon I presented to Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria on the occasion of their wedding in 1810, and which was subsequently bequeathed by the empress to Grand Duke Leopold II of Tuscany. The necklace alone comprises 32 emeralds (the center emerald weighs 13.75 metric carats), 874 brilliants, and 264 rose diamonds.

When Marie-Louise left Paris on March 29, 1814, she took all her jewelry with her; she had to return the Crown Jewels to the emissary of the Bourbons, but kept her personal jewelry items. She bequeathed the emerald parure to her cousin Leopold II of Habsburg, Grand Duke of Tuscany, whose descendants kept it until 1953, when it was sold to the jeweler Van Cleef & Arpels. The emeralds from the tiara were then sold one by one; a wealthy American collector bought the tiara and had it set with turquoises instead of emeralds before bequeathing it to the Smithsonian Institution in 1966. The comb was transformed, but the necklace and pair of earrings were fortunately preserved in their original state, and joined the Louvre's collection in 2004 thanks to the Fonds du Patrimoine, the Friends of the Louvre, and the museum's management.

|

|

The most famous of the British crowns is the Imperial State Crown. This was re-made for the coronation of King George VI, in 1937 and is set with over 3,000 gems. The stones were all transferred from the old Imperial Crown, which had been re-made on a number of occasions since the 17th century, most recently for Queen Victoria in 1838. This crown incorporates many famous gemstones, including the diamond known as the Second Star of Africa (the second largest stone cut from the celebrated Cullinan Diamond), the Black Prince’s Ruby, the Stuart Sapphire, St Edward’s Sapphire and Queen Elizabeth’s Pearls. The Sovereign traditionally wears the Imperial State Crown at the conclusion of the coronation service, when leaving Westminster Abbey. It is also worn for the State Opening of Parliament.

|

|

The legendary Koh-i-Nur (‘Mountain of Light’) diamond, presented to Queen Victoria in 1850, is now set in the platinum crown made for the late Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother for the 1937 coronation. This diamond, which came from the Treasury at Lahore in the Punjab, may have belonged to the early Mughal emperors before passing eventually to Duleep Singh. It was re-cut for Queen Victoria in 1852 and now weighs 106 carats. Traditionally the Koh-i-Nur is only worn by a queen or queen consort: it is said to bring bad luck to any man who wears it.

The Koh-i-noor, which means 'Mountain of Light' in Persian, was first recorded in 1306. A Hindu text at the time said: 'Only God or woman can wear it with impunity'.

Along with the Peacock Throne, Nādir Shāh of Iran brought the Koh-i-Noor to Persia in 1739. It was allegedly Nādir Shāh who exclaimed Koh-i-Noor! when he finally managed to obtain the famous stone,and this is how the stone gained its present name. There is no reference to this name before 1739. After the assassination of Nādir Shāh in 1747, the stone came into the hands of his general, Ahmad Shāh Durrānī of Afghanistan. In 1830, Shujāh Shāh Durrānī, the deposed ruler of Afghanistan, managed to flee with the diamond. He went to Lahore where Ranjīt Singh forced him to surrender it. Finally, Britain took it as part of the Treaty of Lahore, when it took control of the Punjab, in 1849.

The jewel was seized by the Empire's East India Company as one of the spoils of war and presented to Queen Victoria in 1850.

Prince Albert ordered the diamond, then weighing 186 carats, be recut to improve its brilliance.

It was reduced in weight by 42 per cent and cut into an oval brilliant weighing 109 carats.

The Koh-i-noor was then mounted into Victoria's crown among 2,000 other diamonds. |

The Imperial Crown of Russia

The court jewellers Pauzié and J. F. Loubierin made, this magnificent, Imperial Crown for Empress Catherine II in 1762. Its hemispheres are in open metalwork bordered with a row of 37 very fine, large pearls. They rest on a circlet of nineteen very large diamonds set between two bands of diamonds above and below.

Crafted by Cartier in 1921 - this tiara is to be worn on the forehead, parallel to the line of the brows. It has 577 brilliant and rose cut diamonds, designed for the Tysckiewisz family. The central stone was once a jonquil yellow diamond of over 71 carats. It was eventually replaced with this large star sapphire. As a bit of a surprise, the central element is mounted en tremblant so that it can move slightly when worn. ~ Attire's Mind

|

| Gold Greek and Etruscan hinged bangle, 1880 to 1885 , Pforzheim, Schmuckmuseum |

|

| Silver gilt necklace by August Kiehnle, circa 1885, Archeological revival style from the 4th century B.C.- Greek , Pforzheim, Schmuckmuseum |

|

| A hat decoration for Fathali Shah of Iran, who wore it on a tall black woolskin hat. It can be clearly seen on a number of minature paintings of Fathali Shah, usually holding two white egret feathers.

|

|

| A Tiara in the Iranian Crown Jewels |

|

| A Tiara in the Iranian Crown Jewels |

|

| A Ruby Tiara in the Iranian Crown Jewels |

|

| The Noor-ol-Ain diamond Tiara became part of the Iranian Crown collection after Nader Shah of Iran invaded Northern India in 1739 and occupied Delhi. This extremely rare color of diamond came from the Golconda mines in Northern India, most likely the Paritala-Kollur Mine in Andhara Pradesh. According to legend, the Shah returned the crown of India to the Mughal emperor and took all of their vast treasure in exchange. |

|

| The Shield of Nadir Shah |

|

| A necklace in the Iranian Crown Jewels |

|

| A circa 1770 watch with works by Pierre Viala, Geneva , Pforzheim, Schmuckmuseum |

|

| A gem encrusted pitcher in the Iranian Crown Jewels |

|

| A gem encrusted dish cover in the Iranian Crown Jewels |

|

| Marriage Necklace (Thali), late 19th century, India (Tamil Nadu, Chetiar), gold strung on black thread, bottom of central bead to end of counterweight: L. 33 1/4 inches (image courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Cynthia Hazen Polsky, 1991) |

|

| Jeweled Bracelets (500–700), made in probably Constantinople, gold, silver, pearl, amethyst, sapphire, opal, glass, quartz, emerald plasma, overall: 1 7/16 x 3 1/4 inches (image courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917) |

The Empress Josephine tiara, created in ca.1890.

This exceptional jewel is referred to as 'The Empress Josephine Tiara' on account of the fact that the briolette-cut diamonds in the tiara were a gift from Tsar Alexander I of Russia to the Empress Josephine. The Tsar used to bring presents for Josephine when he visited her at La Malmaison, following her divorce from Napoleon.

This was one of the rare tiaras made by Fabergé jewelry house, crafted by their Finnish master jeweler August Holmström.

After the Russian Revolution the Leuchtenberg family sold the tiara and it was bought by the Belgium royals after World War I. When Queen Elisabeth of Belgium passed away her son Prince Charles Theodore inherited it in 1965. The tiara then passed nto Queen Maria Jose’s hands when Charles Theodore passed away in 1983. Princess Maria Gabriella inherited the tiara in 2001 and later put the tiara up for auction in 2007.

In 2007 it went up for auction at Christie's in London, fetching over £1 million and was bought by Fabergé super-collectors, the McFerrin family, and is on permanent loan to the museum along with 600 other Fabergé treasures.

Art Nouveau, and Jugendstil Jewelry

|

| Pendant-brooch, designed by C.R. Ashbee and made by the Guild of Handicraft, about 1900, Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

Contemporary jewelry style has appeared in the 1930s , influenced by various artistic movements including Art Nouveau, cubism, minimalism, dadaism, pop arts and so on. The pieces of this

genre moved from personal adornment to wearable art due in part to the

advent of new materials that were created and manufactured around the

same time including various synthetic materials and artificial gemstones. Moreover, other metals were used instead of the traditional gold and silver, such

as stainless steel and copper, to make pieces more affordable as well as

interesting.

|

Lucien Falize (1839 - 1936), A gold, enamelled and gem-set pendant, Paris, circa 1880

Lucien Falize was born in Paris, France in 1839. His father was renowned jeweler Alexis Falize. His Second Empire (Napoleon III) designs were very popular, and his collaboration with Antoine Tard resulted in the

production of a number of jewels with matt cloisonné enamels in a Japanese-inspired style that were always associated with him.

Lucien was also a great admirer of Japan as was his father. He extensively studied the albums of Hokusai prints borrowed from the connoisseur and critic Philippe Burty, the writer Théophile Gautier, the ceramist François-Eugène Rousseau, or purchased from the famous Orientalist Madame Desoye. Models were also available in the Encyclopédie des Arts Décoratifs de l’Orient. Lucien was a great advocator of careful studies of Japanese art and culture.

In 1862, Lucien visited the International Exhibition in London and saw the first display of Oriental works of art. In 1867, Lucien and Alexis saw Christofle’s display of cloisonné enameled objects at the Expositon Universelle.

|

|

Lucien Falize (1839 - 1936), A gold, enamelled pendant, Paris, circa 1880

Alexis Falize retired in 1876; and Lucien who had been in partnership with his father since 1871, took over the firm. In 1878, Lucien participated in the Exposition Universelle, exhibiting for the first time under his name. He was awarded the Légion d’Honneur and a Grands Prix. The other two were given to Oscar Massin and Frédéric Boucheron.

Lucien found limitless inspiration in the Renaissance. He reproduced portraits in basse, taille enamel to great effect. In 1880, Germain Bapst, descendant of the famous Crown Jewelers, approached Falize and offered him a partnership between the two firms. Lucien agreed, and the new firm Bapst et Falize was opened at 6 Rue d’Antin that same year. In 1889, they exhibited together at the Exposition Universelle. Lucien’s contribution earned him the decoration of Officier de la Légion d’Honneur. Among the pieces in the collection was a bracelet decorated with chamomile flowers and a silver bracelet with two pigeons and verses taken from La Fontaine’s poem of the same title.

|

|

Georges Le Saché (1849 - 1919?), Pendant and chain in 18ct yellow gold, set with a carved ivory figure of a nymph with flowing yellow gold hair surrounded by enamelled Wisteria within a border of yellow gold scrolls

Georges le Saché was an important jewellery designer and manufacturer who came from a family of artists and engravers. His father, Emilé Le Saché, was a draughtsman and line engraver. His mother had a modest business selling jewellery at the Palais Royale. Le Saché spent his youth in painter’s studios, desperate to become an artist. His parents, seeking a more stable career for their son, sent him to Germany to join Friedman: an important German jeweller.

In 1866, following this initial experience in the jewellery business, Le Saché went to London to apply his artistic talents in various areas of the decorative arts. With the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war, Le Saché returned home and joined the 1st Battalion of the Mobile Seine Regiment. He fought bravely between September 1870 and March 1871. Following the war Le Saché returned to London and joined the renowned Parisian jewellers Falize as a designer and collaborator. He spent five years with Lucien Falize learning the jeweller’s craft and becoming a skilled manufacturer. In 1877 Le Saché married the daughter of Baucheron, who was a partner in the firm Baucheron & Guilian, one of the most important manufacturing jewellers of the period. Le Saché worked for the family firm and eventually took over the business. He became one of the most sought-after manufacturers in Paris, supplying all the best jewellery houses with their prime exhibits at the various International Exhibitions. He worked in both bijouterie and joaillerie, producing a rather formal version of Art Nouveau. Le Saché ran his own workshop for 30 years and always kept his works anonymous. In 1901 Georges Le Saché was awarded a silver gilt plaque by the Chambre Syndicale de la Bijouterie to recognise his distinction as a jeweller and designer. This was the highest accolade which was richly deserved. Georges Le Saché’s makers mark (LS within a horizontal lozenge) was deleted on 6th January 1920 |

|

Levinger & Bissinger

Jugendstil Pendant/Brooch the design attributed to Otto Prutscher

Austrian architect and designer Otto Prutscher, the son of a traditional Viennese cabinetmaker, attended the Fachschule für Holzindustrie. In 1897 he entered the Kunstgewerbeschule in Vienna, where he studied with Franz von Matsch (1861–1942) and Josef Hoffmann. Prutscher’s work, strongly influenced by Hoffmann and contemporary Secessionist style, began to attract attention during his student years, and in 1900 a number of his designs were published in Das Interieur. After completing his studies (1901), Prutscher collaborated with Erwin Puchinger (1876–1944) on a series of interiors in Paris and London that won widespread praise. In 1903 he became an assistant at the Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt, and in 1909 he was appointed to a post at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Vienna, where he taught with several interruptions until his retirement in 1946. In the years prior to World War I, Prutscher designed numerous houses and interiors in Vienna and in the provinces, including the Flemmich House in Jägerndorf, Austrian Silesia, and the Villa Rothberger in Baden. His early designs drew on Jugendstil geometric formal language developed by Hoffmann and others. By 1908, however, his works reflect a growing emphasis on classical forms as well as native folk motifs similar to Hoffmann’s contemporary idiom.

|

|

Emile Olive (1852-1902), An Impressive Belle Epoque Brooch/Pendant by Fonsèque & Olive Gold Silver Plique-à-jour enamel Emerald Diamond Pearl French, c.1895

Emile Olive succeeded Georges Le Saché as designer for Lucien Falize. He left Falize in 1885 to form a partnership with Georges Fonsèque in Paris. After Olive’s death in 1902 Fonseque continued the business for a further twenty years. This pendant is an exceptional example of the fusion of Japonisme and Art Nouveau in France. The background in plique-à-jour enamel represents a lily pond in the Japanese cloisonné manner on which a magnificent blister pearl set in gold appears to float. The fine diamond-studded frame surround shows the elegant and characteristic swirls of the French Art Nouveau style.

|

|

| French 2nd Empire, Serpent Bangle

Gold Enamel Ruby Diamond, c.1865 |

|

| Charles Boutet de Monvel (1855-1913),Peacock Pendant, Gilded silver Plique-à-jour Ruby Emerald Pearl, French, c.1904 |

|

| Jugendstil Buckle

Silver Enamel Chalcedony, Max Joseph Gradl (1873-1934) for Theodor Fahrner, German, c.1900 |

|

| Meyle & Mayer (Pforzheim) Jugendstil Floral Locket Silver Enamel Mirror Pendant, Dragonfly German, c.1900 |

|

Silver, enamel & chalcedony, 'TF' Theodor Fahrner monogram 'FM' Ferdinand Morawe monogram, '935' & 'Depose'

Joseph

Maria Olbrich was a founder member of the Vienna Secession in 1897. In

1899, at the invitation of the Grand Duke of Hesse, Olbrich set up the

Artists' colony at Darmstadt, thereby intermingling the styles of

Austria & Germany.

|

|

Skonvirke Brooch, Kay Bojesen (1886–1958),

Kay

Bojesen was born in Copenhagen, Denmark. He first trained to be a

grocer, but in 1906 began working for Danish silversmith Georg Jensen.

The Danish Museum of Art & Design describes his early work as being

in an Art Nouveau style, likely due to Jensen's influence. His later

work was simpler and more functional. In 1931, Bojesen was one of the

key founders of the design exhibition gallery and shop called "Den

Permanente" (The Permanent), a collective which aimed to exhibit the

best of Danish design.

|

|

Charles Robert Ashbee (1863 -1942), Guild of Handicraft Brooch, English. Circa 1898

Charles

Robert Ashbee was born in London, the son of a prosperous city

merchant. Educated at Wellington College and King's College, Cambridge,

he was articled to G. F. Bodley. He became a designer and follower of

the Arts and Crafts Movement. He founded The Guild of Handicraft in

London and was influenced by William Morris and John Ruskin.

In 1902 Ashbee undertook his grand experiment and removed the entire

Guild to Chipping Campden in the Cotswolds. For a while the Guild's

affairs prospered, but from 1905 the receipts from the craft work fell

off disastrously and by 1907 the company was forced into voluntary

liquidation. Ashbee continued throughout this period with his

architectural practice, which brought in a number of decorative

commissions to the Guild.

|

|

| Charles Robert Ashbee (1863-1942) - Guild of Handicraft, Brooch/Pendant,

c. 1900 - Enamel on copper and silver with cabochon amethyst \ JV |

|

| Art Nouveau Aqua-Organic Brooch European. Circa 1900 Gold n |

|

Dorrie Nossiter. Pin brooch.

Dorrie

Nossiter (1893 – 1977) an English jeweller and jewellery designer from

Aston, near Birmingham, crafted precious jewellery of her own designs in

the English Arts and Crafts Tradition. Her work is known for her use of

colour and floral and curvature lines using gemstones in motifs.

Nossiter was educated at the Municipal School of Art in Birmingham from

1910 to 1914. By 1935 she was living in London where her work was shown

in the "Art by Four Women" exhibition at Walker's Gallery, London.

Nossiter would go on to exhibit there from 1935 to 1939.

|

|

Sibyl Dunlop (1889-1968), Arts & Crafts Pendant/Brooch Silver Opal Doublet Amethyst Chalcedony, British, c.1925

Sibyl

Dunlop (1889 - 1968) was a British jewellery designer, best known for

the jewellery and silver objects in the late Arts and Crafts style that

she produced in the 1920s and 1930s.

Dunlop was born in Hampstead, London to Scottish parents and finished

her schooling in Brussels, where she became interested in jewellery

design and underwent some basic training. She established a workshop

and shop at 69 Kensington Church Street, London W8, and in the early

1920s was joined by W. Nathanson as her principal craftsman. Dunlop's

work is characterised by the use of semi-precious and precious gems,

such as chalcedony, chrysoprase, moonstone, amethyst, agate, quartz and

opals, often cabochon rather than facet-cut gemstones, set in silver in

symmetrical patterns, often inspired by nature. One of her most famous

designs is the 'Carpet of Gems' symmetrical setting. The gemstones were

cut for Dunlop by lapidaries in Germany. Dunlop's work is often

confused with that of another female jewellery designer of the same

period, Dorrie Nossiter. The business closed at the outbreak of World

War 2 in 1939 and Dunlop never returned to work due to ill health. After

the war Nathanson re-started the business and continued producing

jewellery and silver under Dunlop's name until he retired in 1971.

|

|

| Art Nouveau Gold, Sapphire, and Plique-a-Jour Enamel Pendant, Marcus & Co. |

|

| Dorrie Nossiter (1893-1977). Arts & Crafts Pendant Necklace Gold

Silver Jade Sapphire Tourmaline Pearl. British, c.1925 |

|

| Ludwig Knupfer for Theodor Fharner, Jugendstil Brooch Silver Enamel Chalcedony |

|

| Arts & Crafts silver necklace set with moonstones. English. Circa

1900. Central panel Frances Thalia How exhibited 1896-1928 & Jean Milne exhibited

1904-1917. |

|

| A domed silver

Arts & Crafts brooch decorated with very fine wirework and gold

bobbles set with a citrine and three mother- of- pearl plaques. British.

Circa 1900. |

|

Philippe Wolfers(1858-1929), Pendant - c. 1900

Wolfers trained in the workshop of his father, an affirmed goldsmith, in Brussels, Belgium. His first designs for silver works and jewelry were influenced by Japanese craftwork and naturalism.

In 1897 he concentrated mainly on jewelry and started to work with ivory, a fine material never used before him and which came from Congo, the Belgian Colony in Africa.

The success was immediate, as he opened branches of his jewelry business in Antwerp, Liège, Ghent, Düsseldorf, London and Paris.

In 1909, Wolfers commissioned Belgian Art Nouveau architect, Victor Horta, to build his headquarters in Brussels. He was also one of the finest glassware designers for the Belgian glass manufacturer Val Saint-Lambert.

In 1908, he produced sculptures, ceramics, furniture and metalwork; his style became more geometrical and abstract and reached its climax at the 1925 Arts and Crafts Exhibition in Paris.

The outstanding works of Philippe Wolfers were of great importance for the entire Art Nouveau jewelry.

|

|

A rich blue

sapphire and a luminous white pearl set in a free-flowing Art Nouveau

stickpin. A wonderful example of the imaginative designs of the early

1900s. Created by Hans Brassler in 14kt gold, circa 1910.

Hans Brassler was born in Germany, studied jewelry design in Paris and is rumored to have medalled at the 1900 Exposition Universelle. In 1909 he founded The Brassler Company in Newark, New Jersey where he served as artistic director and chief designer. Over the next few years he played with the Art Nouveau, Arts & Crafts, classical and even early Art Deco themes of the early 1900s to create innovative, original cufflinks, brooches, pendants and other jewels.

Hans Brassler remained affiliated with The Brassler Company until 1916. In 1933 the remaining assets of the firm were acquired by the jewelry maker Jones & Woodland, later acquired by Krementz & Co.

|

|

Jessie M. King

(1875-1949) Liberty & Co. Suffragette Pendant. A gold pendant set

with two mauve/pink tourmalines within a border of green enamelled

leaves and with a pearl drop.

Jessie Marion King was born in Bearsden, near Glasgow. Her father was James Wat(t)ers King, a minister with the Church of Scotland and her mother was Mary Anne Anderson. She received a strict religious education and was discouraged from becoming an artist. Jessie M. King began training as an Art teacher in 1891 at Queen Margaret College (Glasgow). In 1892 she entered the Glasgow School of Art. As a student, she received a number of awards, including her first silver medal from the National Competition, South Kensington (1898).

King was made Tutor in Book Decoration and Design at Glasgow School of Art in 1899. Her first published designs, and some people believe her finest, were for the covers of books published by Globus Verlag, Berlin between 1899 and 1902. The publisher was a subsidiary company of the great Berlin department store, Wertheim's.

King was influenced by the Art Nouveau of the period and her works correspond in mood with those of The Glasgow Four.

She made a Grand Tour of Germany and Italy in 1902 and was influenced by the works of Botticelli. In the same year her binding for "L'Evangile de L'Enfance" was awarded a gold medal in the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art, held in Turin. King became a committee member of the Glasgow Society of Artists (1903) and a member of the Glasgow Society of Lady Artists (1905).

Her contribution to Art Nouveau peaked during her first exhibitions, Annan's Gallery in Glasgow (1907) and Bruton Street Galleries, London (1905). She married artist Ernest Archibald Taylor in 1908 and moved with him to Salford where their only child, daughter Merle Elspeth, was born. In 1910 they moved on to Paris where Taylor had gained a professorship at Ernest Percyval Tudor-Hart's Studios. In 1911 King and Taylor opened the Sheiling Atelier School in Paris. Her works in Paris are considered as influential to the creation of the Art Deco movement. King and Taylor moved to Kirkcudbright in 1915 and continued to work there until her death.

|

|

| A silver

pendant of entwined, enamelled serpents surrounding a sapphire, the

pendant with pearl drops. Scottish. Circa 1900. Unmarked |

|

| An Arts &

Crafts, silver pendant set with a central red enamel plaque which is

overlaid with flowering rose branches. Original chain and clasp.

English. Circa 1910. |

|

| An Arts & Crafts, silver pendant set with carnelian stones. Original chain and clasp. English. Circa 1910. |

|

| A silver Arts

& Crafts necklace. The pendant set with a large central heart shaped

moonstone surrounded by wirework scrolls surmounted by a four moonstone

and with a moonstone drop. English. Circa 1900. |

<

|

| This necklace

was made in Pforzheim, Germany, circa 1904. It is attributed to the firm

of Karl Hermann (Hermann & Speck), or to Heinrich Levinger

(Levinger & Bissinger). As it is characteristic of their work but is

not signed. |

|

| Jugendstil

Baltic Pendant, Silver Amber, Polish, c.1910

|

|

| Heinrich

Levinger , Jugendstil Stylised Tree Pendant

Possibly designed by Otto Prutscher, Silver Enamel Pearl-- Schmuck in

Deutschland und Osterreich 1895-1914, Ulrike von Hase, 1977, p.328-329 |

|

Albert Edward

Jones, Arts and Crafts chatelaine. Made by the silversmithing firm of A

Edward Jones, estd 1902.

The ceramic cabochons are likely to have been

made by the Ruskin Pottery established in 1898. In the early 1900s, the

Ruskin Pottery introduced these small round cabochons, which they called

enamels or plaques. They were used as gems for inserting into wood,

metal, and jewellery. They became a major part of the pottery's output

over the next few years. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. |

|

| Buckle and belt tag, Henry Wilson About 1905, London Silver, cast, chased, enamelled and mounted with cabochon-cut stones. Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

|

| Necklace Charles Robert Ashbee, 1901 - 1902, London, Silver and gold, set with blister pearls, diamond sparks and a demantoid garnet for the eye, with three pendent pearls, Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

|

| Brooch, Charles Desrosiers, Paris. 1901, Gold and enamel, Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

|

| Pendant, Archibald Knox, About 1900, Birmingham, Enamelled gold, Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

|

Archibald Knox. Necklace: gold, pearl and enamel, 1900-4.

Knox, was an immensely talented, though extremely modest man. He made his way to London from his home, the Isle of Man, in the waning years of the 19th century, at the encouragement of another eminent designer of that period, M. H. Baillie Scott. Although undocumented, it is also believed that Baillie Scott introduced Knox to Dr. Christopher Dresser in whose London studio Knox worked for a few years before joining the very successful London design firm, the Silver Studio that had been founded in 1880. Knox followed Harry Napper, a colleague from Dresser’s employ, to the Silver Studio. A gifted designer in his own right, Napper joined the Silver Studio to manage it after the death of Arthur Silver and until his two sons, Rex and Harry, reached majority. It was at the Silver Studio in late 1897 that Knox began his mature professional career, designing a variety of wallpaper, textiles, silver and pewter objects. Eventually Knox began producing more and more metalwork designs that were sold to Liberty’s for its new Cymric line of silverware and for what was to become its Tudric pewter line a few years later. It was during this period that Knox produced his first jewellery designs that included brooches and buckles. When Arthur Silver’s sons, Rex and Harry, came of age in 1900 and assumed joint directorship of the firm, Harry Napper elected to leave, embarking on a successful free-lance career that included continued work with the Silver Studio. Perhaps encouraged by Napper’s example, or by a desire to be fully independent, Knox left as well, returning to Man around 1900. By then, Knox’s value to Liberty’s had been clearly established, so much so that he no longer needed the Silver

Studio to act as his agent. Now, from afar, Knox became the principle creative engine that drove what was to become Liberty’s near decade-long dominance of the commercial decorative arts field.

|

|

| Archibald Knox |

|

| Archibald Knox Brooch for Liberty |

|

| Archibald Knox Brooch for Liberty |

|

| Necklace, Designed by Alfredo Castellani (1853 - 1930), Rome, Italy, 1925. Gold mounted with 21 scarabs of cornelian, Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

Faberge jewelry, The State Hermitage Museum

Peter Carl Faberge was one of the most famous jewellers in history, best known for the magnificent jewelled Easter eggs that he created for the Russian royal family. He was the eldest son of Gustav Faberge, a Baltic German jeweller of French Huguenot ancestry who moved from Livonia (modern Estonia) to St. Petersburg in 1842 and opened the House of Faberge on Bolshaya Morskaya Ulitsa in the Russian capital.

|

|

Easter-eggs by Faberge

Alexander III ordered the first Faberge egg (the First Hen Egg) as an Easter gift for his wife, Empress Maria Fyodorovna, in 1885. The egg, made of gold covered with white enamel, opened to reveal a matte yellow gold yolk which contained a gold hen with ruby eyes. The Imperial Eggs brought the House of Faberge immediate international success. Eggs were presented to Romanov relatives in royal and aristocratic houses throughout Europe, and smaller versions worn as pendants became highly fashionable accessories. The Faberge output was not limited to eggs, however. The company produced all types of jewellery, ornaments and tableware, with branches in Moscow, Kiev, Odessa and London. The House of Faberge became the largest jewellery manufacturer in Russia, producing over 150 000 pieces by the time of the October Revolution.

|

|

| Brooch, Possibly Van Cleef & Arpels, Paris, About 1930, Platinum and gold set with baguette- and brilliant-cut yellow diamonds, emeralds, sapphires and rubies, Victoria Albert Museum, London |

|

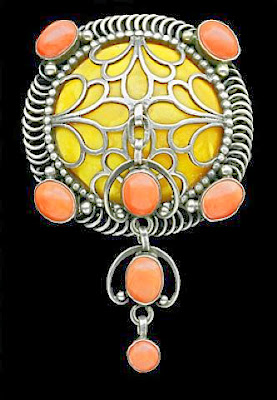

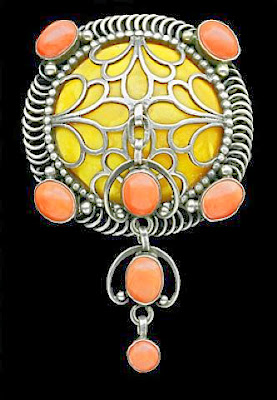

Levinger & Bissinger Plaque-de-cou

|

|

| Jean Auguste Dampt Stick Pin |

|

| Felix Rasumny Art Nouveau Brooc |

|

| Maurice Daurat Grasshopper Pendant |

|

| Auguste Gross, Art Nouveau Brooch |

|

| Joë Descomps Pendant / Brooch |

|

| René Beauclair, Fuchsia Brooch |

|

| Charles Boutet de Monvel Pendant |

|

| Henri Vever Cloak Clasp |

|

| Edouard -Aime Arnould Buckle |

|

| Rene Lalique Ring |

|

| Georges le Turcq Ring |

|

| Ferdinand Zerrenner Attrib. |

|

| Max J. Gradl Buckle for Fahrner |

|

| Wiener Werkstatte Brooch |

|

| Meyle & Mayer, Art Nouveau Locket |

|

| Georg Kleemann, Brooch for Fahrner |

|

| Georg Anton Scheid Brooch |

|

| Bernard Hertz Skonvirke Brooch |

|

| Murrle Bennett & Co Brooch |

|

| Pair of gold, enamel and diamond bracelet, David Webb.

Born in Asheville, North Carolina, David Webb founded his eponymous jewelry line after moving to New York City in 1948 at the age of 21. His long and illustrious career came to an abrupt end with his untimely death in 1975. However, his archive includes more than 40,000 original drawings, sketches, and production records. - |

|

| Gold, peridot and emerald brooch, David Webb |

|

| White enamel and diamond crab long chain, David Webb |

|

| Green fish, Gold, enamel, cultured pearl, ruby and diamond brooch , David Webb |

|

| White snake, enamel, ruby and diamond brooch, David Webb |

|

| White cow, enamel, emerald and diamond brooch, David Webb |

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License.

Wow,What a amazing collections.These collections are unique.Simple designs but looking great.Thank you.Zarah from Bizbilla

ReplyDeletewow

ReplyDelete