Abstract

This chapter examines why much modern art and design are frequently experienced as cold, over-intellectualized, and detached from lived human experience, and explores the implications of this condition for the contemporary notion of the “designer as author.” Drawing on philosophical aesthetics and critical theory, the chapter advances a layered argument concerning the dominance of reason, the legacy of conceptual art, and the limits of authorial control in design.

The analysis begins with Nietzsche’s critique of modern culture’s excessive reliance on rationality. While reason—associated with order, clarity, and analytical control—is indispensable to artistic production, its unchecked dominance suppresses the Dionysian dimensions of art: emotion, instinct, ambiguity, and intensity. The chapter argues that great art emerges from a dynamic tension between the Apollonian and Dionysian forces, and that the erosion of this balance has rendered much modern and postmodern art conceptually sophisticated yet experientially hollow.

Building on this framework, the chapter contends that twentieth-century conceptual art and theory-driven design replicate the very error Nietzsche identified in the decline of Greek tragedy. In privileging explanation over presence and idea over experience, such practices relocate meaning from the artwork itself to external discourses—artist statements, academic texts, and theoretical justifications—thereby marginalizing the intuitive, emotional, and spiritual dimensions of aesthetic encounter.

The chapter then turns to the concept of the “designer as author,” interrogating its apparent promise of creative autonomy. While this notion seeks to elevate designers from mere executors to initiators of meaning, the chapter argues that it ultimately rests on a misleading assumption of authorial sovereignty. Drawing on the work of Barthes and Foucault, it demonstrates that meaning does not originate solely with the designer but emerges through the interaction between the work and its interpreters. Authorship, in this view, functions less as a source of meaning than as a retrospective construct generated through interpretation.

Further, the chapter distinguishes between the designer as a material individual and the “designer-as-author” as an interpretive fiction. The perceived authorial voice of a design is not transmitted intact from creator to audience but is continually reconstituted through reception. This openness is not a deficiency but a condition of artistic vitality.

Finally, the chapter addresses the paradoxical burden of authorship, noting how the elevation of creators to the status of “masters” can constrain innovation and inhibit creative freedom. The essay concludes by reaffirming the necessity of tension—between reason and intuition, structure and ambiguity, concept and lived experience—as the foundation of meaningful art and design. Rather than asserting control over meaning, designers are urged to cultivate conditions in which meaning can emerge, transform, and endure through interpretation.

Rose petals let us scatter

And fill the cup with red wine

The firmaments let us shatter

And come with a new design— Hafez of Shiraz (1326–1390)

The Trembling Scepter of Rationalism

Nietzsche's critique in The Birth of Tragedy (1872) opens with a haunting image: Socratic culture, once confident in its rational foundations, now holds "the scepter of its infallibility with trembling hands." Shaken by fear of its own consequences and stripped of its naive faith in eternal validity, theoretical thought "rushes longingly toward ever-new forms, to embrace them, and then, shuddering, lets them go suddenly as Mephistopheles does the seductive Lamiae."

This represents what Nietzsche identifies as the fundamental malady of modern culture: the theoretical man, "alarmed and dissatisfied at his own consequences, no longer dares entrust himself to the terrible icy current of existence." Pampered by optimistic views, he recoils from anything whole, anything bearing nature's full cruelty. He recognizes that a culture built on scientific principles must collapse when it grows illogical—when it retreats before its own consequences.

The symptoms appear throughout modern art. We imitate all the great productive periods, accumulate world literature for comfort, catalog art styles and artists across ages "as Adam did to the beasts"—yet remain "eternally hungry." We become critics without joy or energy, Alexandrian librarians going "wretchedly blind from the dust of books and from printers' errors."

The Apollonian and Dionysian: A Necessary Duality

Nietzsche's brilliant criticism of Euripides advances the thesis that Greek tragedy declined after its zenith with Aeschylus and Sophocles in the early to mid-fifth century BCE. He argues that great tragedy emerged from Greek traditions of music, song, and dance through two opposing yet complementary tendencies: the Apollonian and the Dionysian.

Apollo, god of light, dream, and prophecy, personifies reason and intellect's gentle reign, pushing life toward orderly—perhaps unnatural—arrangements. Dionysus, god of intoxication, embodies emotion and passion, sometimes whipped into self-destructive frenzy. The Dionysian suppresses intellect to live as one with nature, with wine playing an essential role in his cult.

The early fifth-century tragedians reconciled these antithetical tendencies. In the works of Aeschylus and Sophocles—and later in Shakespeare's plays and Wagner's music-dramas—Nietzsche found the ideal synthesis: "Dionysus speaks the language of Apollo, and Apollo, finally, the language of Dionysus, whereby the highest goal of tragedy and all art is achieved."

This duality represents the fusion of Greek poetry's two major currents. The Apollonian element advances serenity and rational imagery, as reflected in Homer's epics. The Dionysian element offers darker insight into humanity's irrational and unpredictable nature, as found in the poems of Archilochus and Pindar.

Euripides, however, failed to maintain this balance. According to Nietzsche, he sought "to excise that original and all-powerful Dionysian element from tragedy and to rebuild tragedy purely on the basis of an un-Dionysian [Apollonian] art, morality, and world-view." By disregarding the Greek psyche's dark and irrational dimensions while focusing almost exclusively on the rational and visible, Euripides occasioned Greek tragedy's decline.

The Conceptual Art Parallel

Had Nietzsche observed twentieth-century conceptual art, he would have recognized a parallel decline. By focusing almost exclusively on aesthetic discourse's dialectics and on process and systems analysis, postmodern conceptual art—with its complete reliance on artists' self-analytic conceptual statements exposing their work's internal logic—has, in Nietzschean terms, contaminated art's essence.

R. Cronk's 1996 essay "The Rise and Fall of (Post-)Modern" describes this transformation:

The new aesthetic made the assumption that beneath art lay an internal logic that could be understood through language theory. These artists were concerned with producing art that established its own context within the dialectics of aesthetic discourse. The intent was to provoke aesthetic sensibilities into the realization of art as a semiotic device. (...) The artist abandoned the search for iconic form in favor of an aesthetic based on propositional logic. He turned from the considerations of formal perception to approach art in self-analytic conceptual terms.

Structuralism and subsequent aesthetic theories entrenched themselves behind a reductive hypothesis denying the numinous art experience's relevance. The symbolic and spiritual were expelled. Presence and significant form no longer mattered. Art establishment aestheticians abandoned transcendent aesthetics for a value system based on "man's greatest attribute—the contemplative intellect."

For Structuralists, the idea and its context became the subject. Medium restrictions vanished. Artists could mix media, include theory and environment as work elements. An artist could place mirrors in the landscape and call it sculpture because the idea, not the object, was the art. Minimalists rejected Formalists' concern for internal relationships; the minimal shape, like the blank canvas, stood for itself without illusion or further signification.

The Limits of Theoretical Understanding

When a culture believes anything can be understood and reformed through theory, philosophical or scientific theory eclipses the world, resulting in theoretical man's domination and art's demise. Yet this illusion of understanding inevitably confronts its own limits, for the unintelligible persists.

In Nietzsche's view, when Euripides challenges the Dionysiac—as when his Pentheus confronts Dionysus in The Bacchae—or when postmodern art challenges aesthetics itself, they seek to eliminate tragic drama and art's Dionysiac basis altogether. They favor new, experimental, audaciously rational drama and conceptual art based on the Apollonian without the Dionysian. This is an impossible goal because the Dionysiac is the Apollonian's precondition; without it, the Apollonian atrophies and withers.

Nietzsche praised Kant and Schopenhauer for clarifying knowledge's limitations. Kant showed that legitimate knowledge rests on categories, but these categories don't apply to things-in-themselves. Science is fundamentally limited by what it cannot grasp: the very ground of a thing's existence in itself. In contrast, Dionysiac art creates the "thing-in-itself."

Yet true art, as Nietzsche explains, requires specific conditions—a "cruel-sounding truth" that "slavery belongs to the essence of a culture." Economic organization concentrates purchasing power in the hands of "a small number of Olympian men" who can afford true art. Nietzsche isn't condoning slavery but diagnosing reality: killing true art perpetuates structural inequity, leaving the masses content with superficial pleasures—hamburgers, cola, ball games—while genuine liberation through art becomes impossible.

The Question of Authorship in Design

In 1996, Michael Rock asked: "What does it really mean to call for a graphic designer to be an author?"

Authorship had become popular in design circles, especially in academies and the murky territory between design and art. The word carries seductive connotations of origination and agency. But determining who qualifies as an author and what authored design looks like depends on how one defines the term and determines admission into this pantheon.

Rock observed that authorship suggests new approaches to design process in a profession traditionally associated with communicating rather than originating messages. However, theories of authorship also serve as legitimizing strategies. Authorial aspirations may reinforce conservative notions of design production and subjectivity—ideas running counter to recent critical attempts to overthrow the perception of design as based on individual brilliance.

Two years later, in 1998, Ellen Lupton responded:

The slogan 'designer as author' has enlivened debates about the future of graphic design since the early 1990s. Behind this phrase is the will to help designers initiate content, to work in an entrepreneurial way rather than simply reacting to problems and tasks placed before them by clients. The word author suggests agency, intention, and creation, as opposed to the more passive functions of consulting, styling, and formatting. Authorship is a provocative model for rethinking the role of the graphic designer at the start of the millennium; it hinges, however, on a nostalgic ideal of the writer or artist as a singular point of origin.

Lupton proposed an alternative: "designer as producer." Production is embedded in modernism's history. Avant-garde artists and designers treated manufacturing techniques not as neutral, transparent means but as devices equipped with cultural meaning and aesthetic character. In 1934, Walter Benjamin wrote "The Author as Producer," attacking the conventional view of authorship as purely literary enterprise. He proclaimed that new communication forms—film, radio, advertising, newspapers, the illustrated press—were melting down traditional artistic genres and corroding borders between writing and reading, authoring and editing.

The Death of the Author, The Birth of the Observer

Perhaps the entire "designer as author" discourse began with Roland Barthes's "The Death of the Author" (1968), which can be reinterpreted in design's context:

A text is made up of multiple writings, drawn from many cultures and entering into mutual relations of dialogue, parody, contestation, but there is one place where this multiplicity is focused and that place is the reader, not, as was hitherto said, the author.

Barthes's starting point is a sentence from Balzac's little-known novella Sarrasine (1830), about an artist who falls in love with a young castrato he believes to be a woman. In S/Z (1970), Barthes became fascinated with this ambiguous tale of mistaken identity. The narrator's mysterious pronouncement about the castrato as the essence of womanhood raises questions: Who speaks? The duped artist? The narrator? Balzac the writer? Balzac the man?

Having explored all possibilities, Barthes concludes it's impossible to determine who uttered the sentiment. In design context, we can reformulate Barthes's conclusion to describe design as a space "where all identity is lost, beginning with the very identity of the body that designs."

According to Barthes's framework, the observer—not the designer—plays the proper witness for the "plural of the design" and provides it with unity. This unity is neither appropriative nor limiting nor owned because the observer remains anonymous, unlike the designer. The designer becomes nothing more than "the instance designing." Thus we can proclaim like Barthes: "the birth of the observer must be at the cost of the death of the Designer."

The Designer-Function

Michel Foucault, in "What is an Author?" (1969), reexamines the author's role by searching in the void created by his death. We can reformulate Foucault's statement as "What is a Designer?" and argue:

We should reexamine the empty space left by the designer's disappearance; we should attentively observe, along its gaps and fault lines, its new demarcations, and the reapportionment of this void; we should await the fluid functions released by this disappearance.

In this gap we find the "designer-function"—the role that has replaced the designer. A designer should be understood as a function of design discourse rather than as an entity unto itself:

The function of a designer is to characterize the existence, circulation, and operation of certain discourses of design within a society.

From this perspective, we can ask with Foucault: What difference does it make who is designing?

It would be as false to seek the designer-as-author in relation to the actual designer as to the fictional illustrator; the "designer-as-author-function" arises out of their scission—in the division and distance of the two.

The Artist's Ambition and the Burden of Masterpieces

In Human, All Too Human, Nietzsche suggests an artist's ambition "demands above all that their work should preserve the highest excellence in their own eyes, as they understand excellence."

Within this Nietzschean framework, as a designer becomes increasingly celebrated, he detaches from himself and obtains an additional identity—a persona as "the designer-as-author" for the public, not as an individual. He assumes the role of "master" through his masterpieces, ceasing to be "serious with regard to himself."

This occurs partly because acclaimed designs outlive their designers. Masterpieces become the posthumous representation of those artists' "lives" while simultaneously taking on lives of their own. One's masterpieces acquire separate identities that further kill the designer-as-author.

Consider David Lean's career trajectory. After The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), which won seven Academy Awards including Best Director, Lawrence of Arabia with seven Oscars including Best Director, and Doctor Zhivago (1965) with three Oscars and a Best Director nomination, Lean became imprisoned by his masterpieces. The harsh critical treatment of Ryan's Daughter (1970) devastated him so deeply that he didn't make another film for fourteen years—as an artist, he was dead during those years. Had those masterpieces not existed, perhaps Ryan's Daughter would have been judged differently, free from the shadow of impossible expectations.

The Implied Designer-as-Author

Employing Wayne Booth's concept of "implied author" in design context—as "implied designer-as-author"—we can follow Alexander Nehamas's formulation in "Writer, Text, Work, Author" to argue that the "implied designer-as-author" is contingent upon the design itself. Even if several designs have been composed by a single designer, their implied designer-as-authors are held to be distinct.

Designers (but not, as we shall see, designer-as-authors) exist outside their designs and precede them in truth, not in appearance only. And precisely for this reason, designers are not in a position of interpretative authority over their designs, even if these are, by law, their property.

Nehamas's notions of author and text align closely with my concepts of "designer-as-author" and "design" in graphic design. Appropriating his framework, we can argue:

The relation between designer-as-author and design can be called "transcendental." Unlike abstract symbols, designer-as-authors are not simply parts of design; unlike actual designers, they are not straightforwardly outside them. The designer-as-author emerges as the agent postulated to account for construing the design as the product of an action. Designs, then, are works if they generate an author; the designer-as-author is therefore the product of interpretation, not an object that exists independently in the world.

The figure of the designer-as-author, contrasted with that of the designer, allows us to avoid the view that understanding a design means recreating or replicating a state of mind someone else has undergone. Designers own their designs as one owns property—legally their own (eigen), yet capable of being taken away while leaving them who they are. Designer-as-authors, by contrast, own their works as one owns one's actions. Their works are authentically their own (eigentlich). They cannot be taken away (reinterpreted) without changing their designer-as-authors, without making the characters manifested in them different or unrecognizable. Designer-as-authors cannot be separated from their works.

Interpretation as Perpetual Contextualization

In this Nehamasian world, interpretation need not directly relate to a design's deeper meaning. Rather, interpretation "is the activity by means of which we try to construe movements and objects in the world around us as actions and their products." Understanding interpretation as activity or action allows one to place a design within a "perpetually broadening" context.

Using Proust's Remembrance of Things Past as Nehamas does, applied to design:

Only when the designer succeeds in designing the flower's very silence and in seeing his experience of that silence as part of the process that finally enables him to become a designer-as-author—that is, only when he takes this experience of "incomplete" understanding itself and gives it a place within the complete account of his life and his effort to become able to design—does his designing begin.

As Nehamas believes, objects' significance lies not in hidden symbolic signification but in their interrelation: "Their significance is their very ability to become part of this design, their susceptibility to description, even if this description is exhausted by their surface. For the design is nothing over and above the juxtaposition of many such surfaces, the meaning of which is to be found in their interrelations."

Consequently, "the designer-author emerges as the agent postulated to account for construing a design as the product of an action."

Conclusion: The Author's Renewed Life

Perhaps it is in this vein that Peter Shillingsburg states in Scholarly Editing in the Computer Age: "The author as initiator of discourse is showing new life, and renewed interest in social institutions has given the author further life as a member of a community."

The designer-as-author, then, exists in the space between death and rebirth—neither the autonomous genius of Romantic tradition nor the mere function of discourse, but rather an emergent figure constituted through the interplay of design, interpretation, and community. This figure maintains the tension Nietzsche identified as essential to art: the Apollonian impulse toward structure and meaning balanced against the Dionysian recognition that something always exceeds our rational grasp.

True design, like true tragedy, requires both elements. The designer who embraces only systematic analysis and conceptual frameworks produces work as lifeless as Euripides' purely Apollonian drama. But the designer who recognizes design as interpretation, as perpetual contextualization, as the creation of surfaces whose meaning emerges through interrelation—this designer participates in the ancient dance between order and chaos, reason and intuition, the explainable and the irreducible.

The question is not whether the designer should be an author, but what kind of authorship emerges when we abandon both the myth of autonomous creation and the reduction of design to pure function. In that space—that gap left by traditional authorship's death—we find something more complex and more honest: the designer-as-author who is simultaneously creator and created, origin and product, master of the work and servant to its autonomous life.

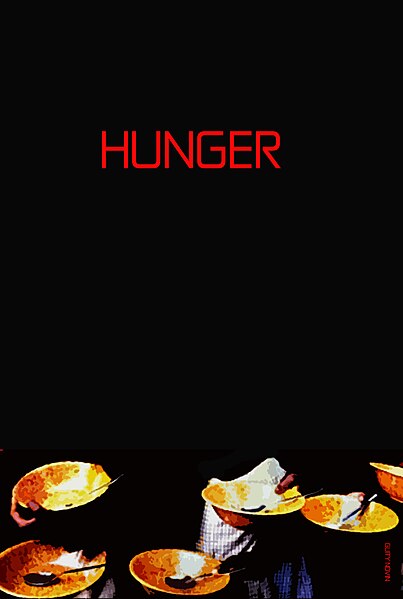

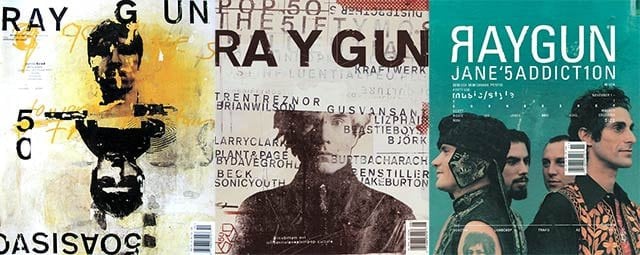

David Carson

David Carson

Stefan Sagmeister

Stefan Sagmeister

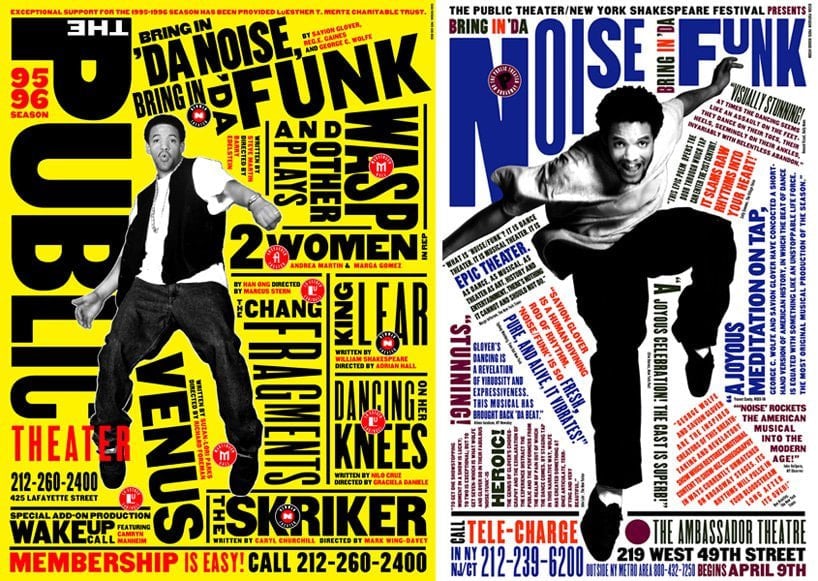

Paula Scher

Paula Scher

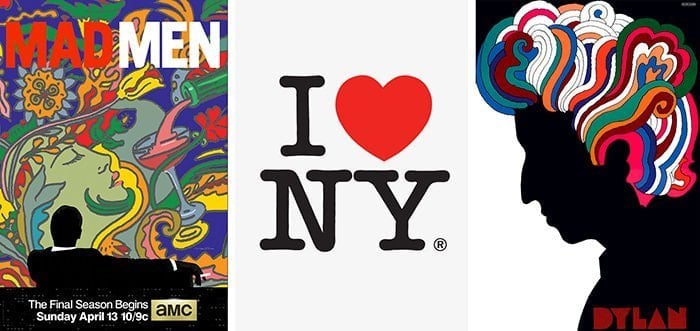

Milton Glaser

Milton Glaser

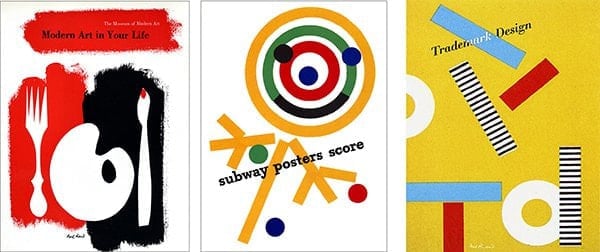

Paul Rand

Paul Rand

Alan Fletcher

Alan Fletcher

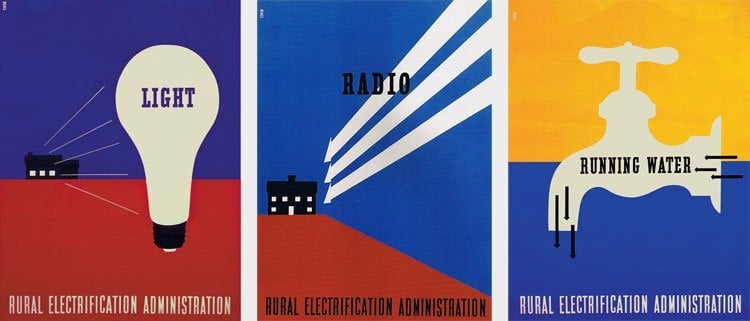

Lester Beall

Lester Beall

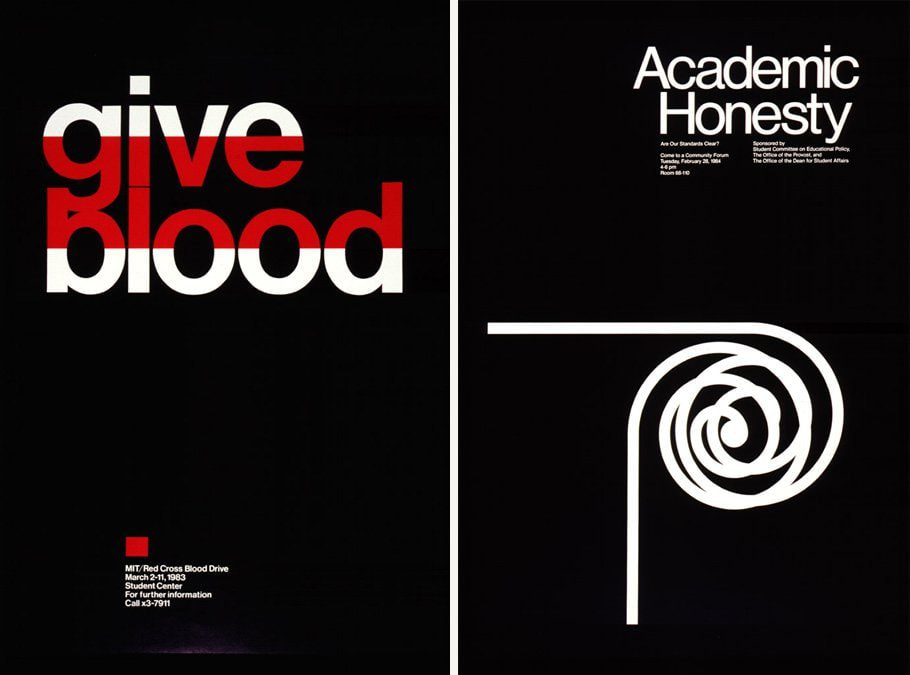

Jacqueline Casey

Jacqueline Casey

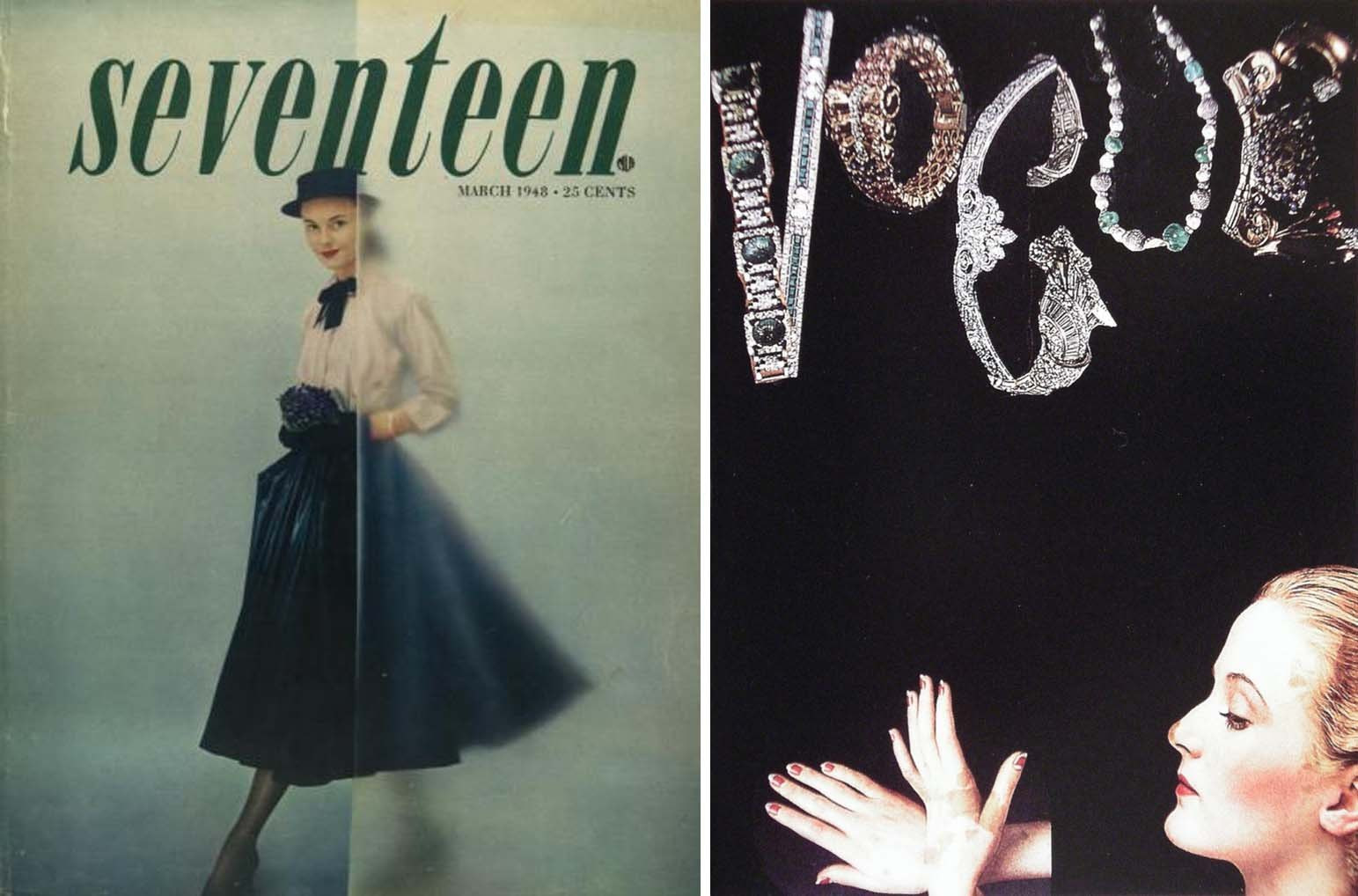

Cipe Pineles

Cipe Pineles

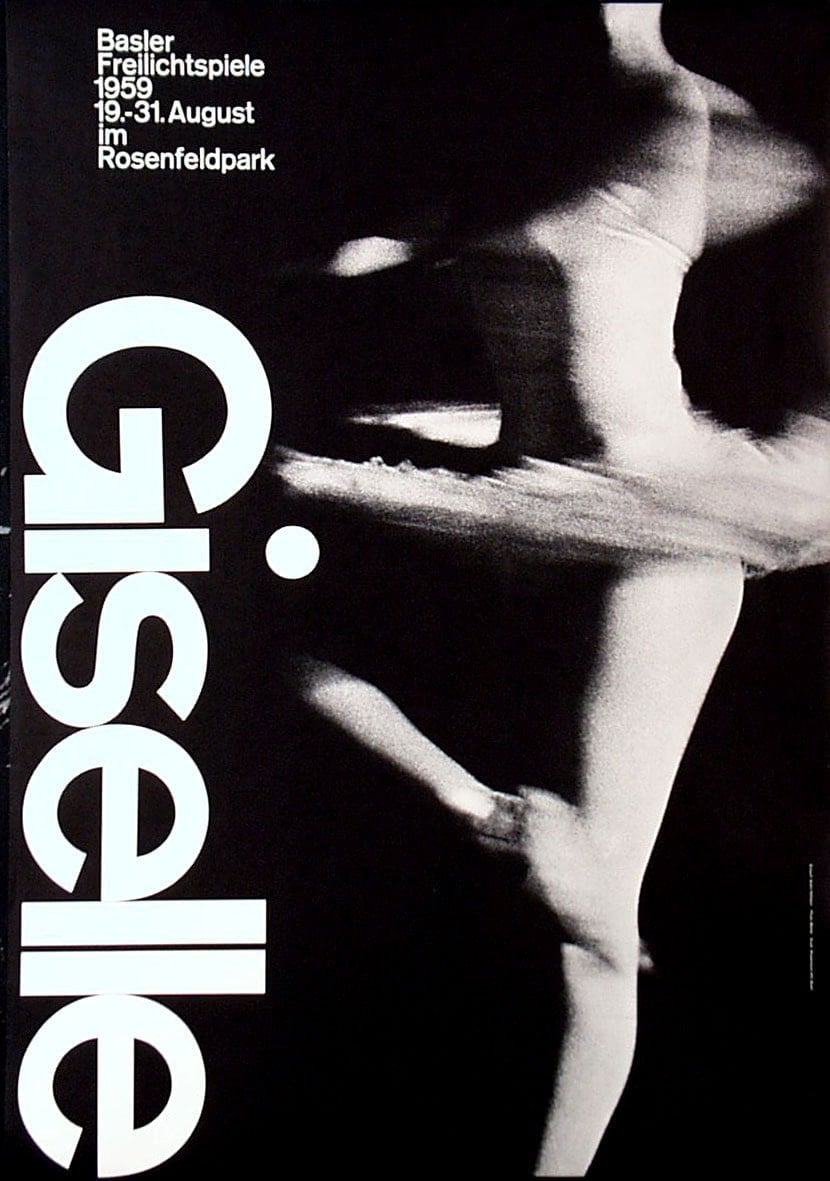

Armin Hofman

Armin Hofmann

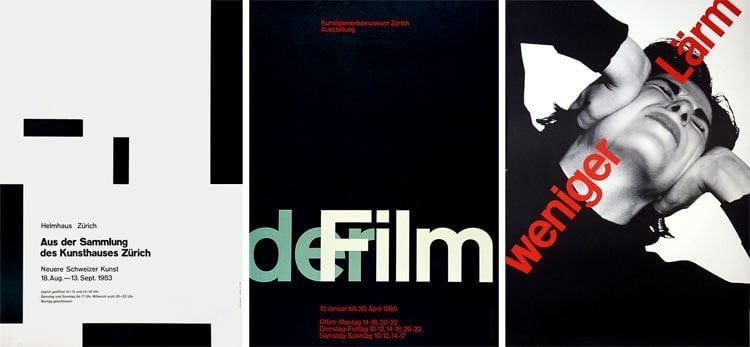

Josef Muller-Brockmann

Josef Muller-Brockmann

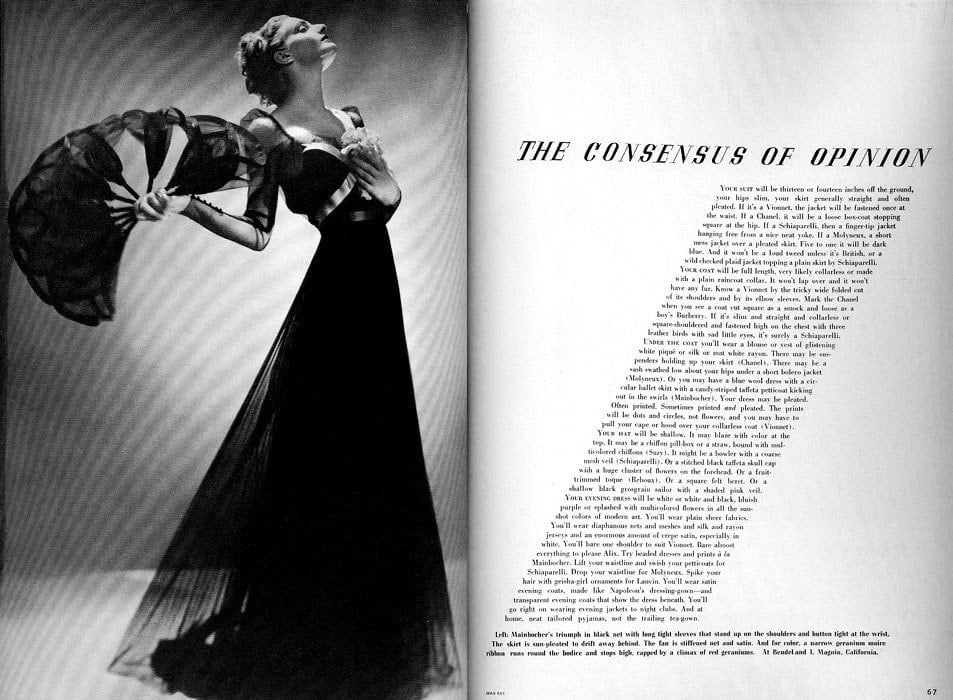

Alexey Brodovich

Alexey Brodovich

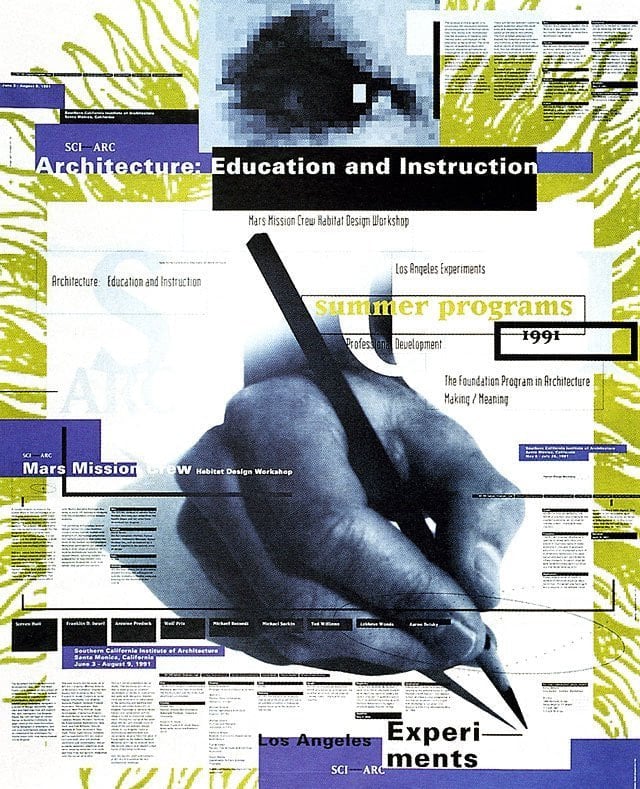

April Greiman

April Greiman

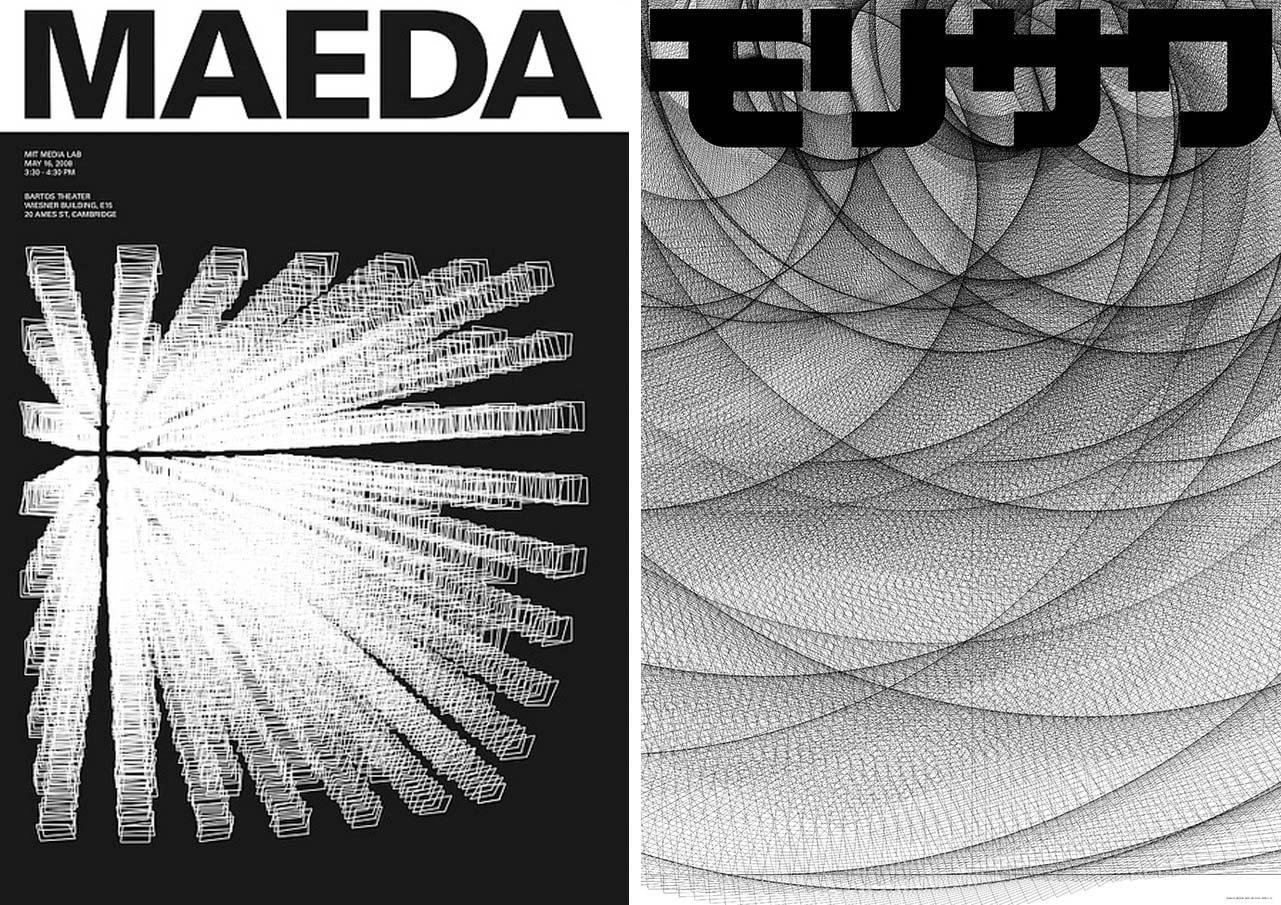

John Maeda

John Maeda

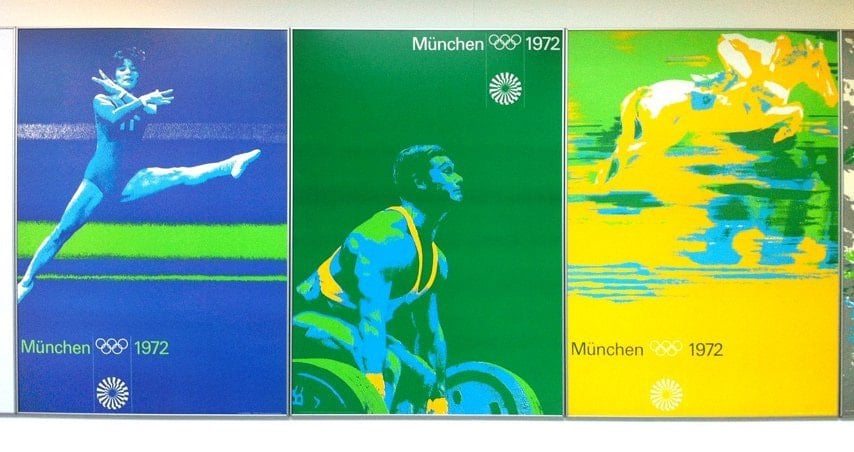

Otl Aicher

Otl Aicher

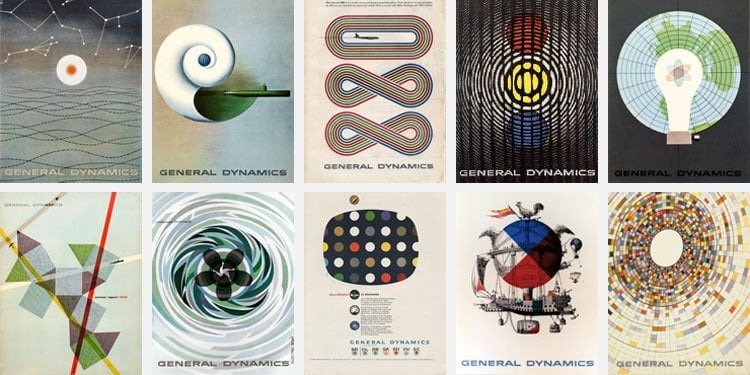

Erik Nitsche

Erik Nitsche

Neville Brody

Neville Brody

A Philosophical and Political Critique

The Chapter offers an appealing diagnosis of modern design’s malaise: excessive rationalism, over-theorization, and a misplaced obsession with authorship have drained art and design of vitality. While this critique resonates emotionally and draws on a long philosophical tradition, it rests on contested assumptions and carries political implications that deserve scrutiny.

1. The romanticization of “feeling” over reason

Philosophically, the post echoes Nietzsche’s critique of rationalism and its alleged suppression of instinct, emotion, and the irrational. While this opposition is rhetorically powerful, it risks reproducing a false dichotomy.

Reason and emotion are not natural enemies. Many traditions—from Aristotle’s phronesis to pragmatism—treat rational judgment as embodied, affective, and contextual. To blame “thinking” for lifeless design may confuse bad thinking with thinking itself. Poorly theorized work does not fail because it is intellectual, but because it is intellectually shallow.

Politically, this critique can unintentionally align with anti-intellectual currents that already threaten democratic discourse. In an era of misinformation, algorithmic manipulation, and populist resentment toward expertise, dismissing theory risks reinforcing the idea that reflection and critique are elitist or alienating rather than necessary.

2. The depoliticization of interpretation

The chapter presents interpretation as open, plural, and liberating. Meaning emerges through interaction, not authorial control. Philosophically, this aligns with post-structuralist thought (Barthes, Foucault), but politically it obscures a crucial reality:

Not all interpretations are equal.

Meaning is shaped by:

power

education

media ownership

cultural capital

institutional gatekeeping

Audiences do not interpret from neutral positions. Museums, platforms, algorithms, and markets structure what can be seen, said, and valued. Treating interpretation as a free-floating human exchange risks masking how meaning is organized and policed in practice.

In this sense, the “death of the author” does not necessarily empower the public—it may simply shift authority to institutions, platforms, or markets that remain invisible in the narrative.

3. The quiet retreat from responsibility

By emphasizing that designers do not control meaning, the essay risks weakening ethical accountability. If meaning always escapes intention, where does responsibility lie?

Politically, this is dangerous terrain. Designers shape:

public information

political messaging

surveillance interfaces

behavioral nudges

algorithmic environments

To say “the audience completes the work” can become a convenient alibi when designs mislead, manipulate, or harm. While no designer controls interpretation fully, designers still structure possibilities, frame choices, and guide attention.

A philosophy of design that dissolves authorship too completely risks absolving designers of responsibility for consequences.

4. The nostalgia embedded in the critique

The post criticizes conceptual art and theory-heavy design while implicitly longing for a return to immediacy, presence, and emotional resonance. Philosophically, this nostalgia assumes that such immediacy ever existed in a pure form.

Historically, art has always been mediated by:

conventions

institutions

patronage

ideology

technology

Even so-called “authentic” art traditions were deeply structured and exclusionary. Politically, nostalgia for a more “human” past can obscure how access to authorship, artistic legitimacy, and cultural visibility were historically restricted by class, race, gender, and empire.

The critique risks idealizing a past that was never as open or humane as implied.

5. The absence of material conditions

Perhaps the most significant political weakness is what the chapter does not address: the economic and technological conditions shaping design today.

Design is increasingly governed by:

platform capitalism

AI systems

corporate branding regimes

precarity and gig labor

attention economics

To frame the crisis of design primarily as a philosophical imbalance between reason and emotion overlooks the structural forces that incentivize speed, clarity, predictability, and quantification. Designers are often not over-theorizing because they want to—but because the market demands legibility, metrics, and justification.

Without addressing political economy, the critique risks becoming aesthetic moralism rather than systemic analysis.

6. Strengths worth preserving

Despite these critiques, the chapter does articulate something important:

It resists authoritarian notions of creative control.

It defends ambiguity against total explanation.

It challenges the cult of genius and individual mastery.

It reminds us that art and design exceed rational capture.

Philosophically, its insistence on limits—on what cannot be fully explained or owned—is a necessary corrective to technocratic arrogance.

Politically, its emphasis on participation and interpretation gestures toward a more democratic cultural space, even if that space is not as free as implied.

Conclusion: A useful but incomplete critique

Philosophically, the chapter is strongest as a warning against intellectual hubris, not against intellect itself.

Politically, it gestures toward liberation but stops short of confronting the power structures that determine who gets to design, who gets to interpret, and whose meanings endure.

The challenge is not to abandon theory, authorship, or rationality, but to situate them within material, ethical, and political realities.

Without that grounding, the call to “let something human come through” risks becoming a beautiful sentiment detached from the very conditions that prevent it.

A Rebuttal to the Philosophical and Political Critique

The critique raises serious concerns about romanticism, responsibility, power, and material conditions. These objections deserve to be acknowledged. However, while they are intellectually respectable, they ultimately misread both the intent and the philosophical depth of the original argument. What follows is a point-by-point rebuttal that reports the criticism accurately while explaining why it does not defeat the core thesis.

1. On the alleged “romanticization” of feeling over reason

The criticism:

The argument is accused of setting up a false opposition between reason and emotion, and of flirting with anti-intellectualism in a politically dangerous age.

The rebuttal:

This objection misunderstands the argument at a foundational level. The essay does not reject reason, nor does it elevate feeling as a superior alternative. It criticizes reason’s imperial ambition—the belief that rational explanation can exhaust meaning.

This is not anti-intellectualism; it is a classical philosophical position shared by Kant, Schopenhauer, Wittgenstein, and even Aristotle, all of whom acknowledged limits to discursive reason. To insist that pointing out those limits is politically irresponsible is itself a category mistake.

Indeed, the real danger today is not skepticism toward theory, but the conflation of explanation with truth—a mindset that underwrites technocracy, algorithmic governance, and the quiet erosion of human judgment. The essay’s insistence on what exceeds theory is therefore not a retreat from reason, but a defense of its proper scope.

2. On interpretation and power

The criticism:

The essay is said to romanticize interpretation as free and plural, ignoring the role of institutions, capital, and cultural gatekeeping.

The rebuttal:

This criticism mistakes ontological openness for sociological naïveté.

The argument that meaning is not authorially controlled does not imply that interpretation is socially unstructured. It simply states a more basic claim: meaning cannot be fully stabilized, even by the most powerful institutions.

Museums, platforms, and markets attempt to regulate meaning precisely because meaning resists closure. Their power is real—but it is never absolute. The essay’s focus is not on denying power, but on explaining why power must constantly reassert itself.

In fact, the claim that interpretation is open is not politically complacent; it is what makes critique possible at all. If meaning were fully determined by institutions, resistance would be incoherent. The essay implicitly affirms the very condition that critical politics depends on.

3. On responsibility and ethical accountability

The criticism:

By weakening authorship, the essay allegedly weakens responsibility—especially dangerous in contexts like political design, surveillance, or AI.

The rebuttal:

This objection conflates control with responsibility.

The argument does not say designers are unaccountable; it says they are not sovereign authors of meaning. Responsibility does not require omnipotence. On the contrary, ethical responsibility begins precisely where control ends.

Designers remain responsible for:

framing choices

shaping affordances

directing attention

enabling or constraining actions

What the essay rejects is the fantasy that designers can fully predict or govern outcomes. That fantasy is far more dangerous politically, because it encourages technocratic arrogance and moral overconfidence.

Acknowledging limits to authorship does not dissolve responsibility—it grounds it in humility, which is a prerequisite for ethical practice in complex systems.

4. On nostalgia and the myth of a purer past

The criticism:

The essay is said to idealize a lost age of authentic art and immediacy, ignoring historical exclusions and mediations.

The rebuttal:

This criticism reads nostalgia where there is none.

The essay does not propose a return to any historical moment. Its references to Greek tragedy or earlier artistic forms are diagnostic, not restorative. They illustrate structural conditions for meaningful art, not models to be revived.

Moreover, the claim that all art is mediated does not refute the argument—it supports it. The essay never denies mediation; it argues against the illusion that mediation can be made total, transparent, or self-sufficient.

Far from idealizing the past, the essay explicitly rejects myths of purity, originality, and autonomous genius. Its critique is directed precisely against those romantic illusions.

5. On the absence of political economy

The criticism:

The essay allegedly ignores capitalism, platforms, AI, precarity, and material constraints shaping design today.

The rebuttal:

This criticism mistakes scope for blindness.

The essay is not a political economy of design; it is a philosophical diagnosis of meaning under conditions of rationalization. Its concern is not why designers behave as they do, but what happens to meaning when explanation replaces experience.

In fact, the essay complements political economy rather than competing with it. Structural forces explain why design becomes over-rationalized; the essay explains what is lost when it does.

Without this philosophical account, political-economic critique risks reducing culture to mere superstructure—instrumental, epiphenomenal, and ultimately disposable. The essay preserves the irreducibility of cultural meaning against that reduction.

6. Why the critique ultimately falls short

The criticism is strongest where it calls for attention to power, institutions, and material conditions. But it overreaches when it treats the essay’s philosophical restraint as political evasion.

The essay does not deny:

power

responsibility

structure

economy

It denies totalization—the belief that any of these can fully explain or control meaning.

That denial is not politically regressive. It is the condition for:

critique

creativity

ethical hesitation

democratic interpretation

Conclusion: Why the original argument still stands

The original essay is not a rejection of reason, authorship, or theory. It is a refusal to let any of them close the world.

Philosophically, it insists on limits.

Politically, it resists domination by explanation.

Ethically, it demands humility rather than mastery.

In an age of AI-generated meaning, algorithmic persuasion, and technocratic confidence, this position is not nostalgic or evasive—it is necessary.

The designer is not dead, but neither is the designer sovereign. Meaning emerges in the space between intention and interpretation, structure and excess, control and failure.

That space is not a weakness of design.

It is where its human significance begins.

No comments:

Post a Comment